AARP Hearing Center

Doctors who care for people with Alzheimer’s now have access to two medications that may be able to modestly slow the progression of the disease — at least for some patients.

The two drugs — Leqembi (lecanemab) and Kisunla (donanemab) — are “transformational,” says Dr. Paul E. Schulz, professor of neurology and director of the Neurocognitive Disorders Center at the McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. “They provide the first inkling that we are on the right path, which gives us great hope that we can continue to tweak things and improve the effects.” Schulz is one of the researchers who studied Kisunla in clinical trials.

Someday, the drugs — or their next generation — might prevent cognitive decline entirely in people whose brains show signs of disease but who don’t yet have symptoms, says Dr. Andrew Budson, chief of cognitive behavioral neurology, VA Boston and professor of neurology at Boston University. “These drugs are an absolute breakthrough for patients today, but even more so for patients tomorrow,” he says.

Yet even with the excitement and potential, there are serious considerations when it comes to these medications. Side effects can occur and can be serious — even deadly. What’s more, the drugs are expensive, with list prices higher than $25,000 a year.

It’s no wonder then, that people who are newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s may have questions. Those with certain risk factors are told, “Talk to your doctor.” But do most doctors have answers?

“In my experience, most neurologists haven’t had a chance to learn about this area of treatment,” says Schulz, one of the researchers who studied Kisunla in clinical trials. “We’re all in the learning curve now.”

AARP interviewed six leading Alzheimer’s specialists to get answers to 15 questions about the new Alzheimer’s drugs.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting an estimated 7.2 million Americans older than 65, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. The disease is marked by progressive memory loss, personality changes, and ultimately, the inability to perform routine daily tasks, such as bathing, dressing and paying bills.

1. How do these two drugs work?

Leqembi and Kisunla are antibodies that bind to the amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s plaques. Those plaques are formed from naturally occurring proteins that build up in the brain and cause problems. Most antibodies in the body are made by our immune system to fight off infections from viruses or bacteria, but these two are produced in the lab. When the antibody sticks to the amyloid molecule, the body’s immune system is alerted to destroy the amyloid, removing it from the brain and potentially slowing the disease.

2. How do the drugs differ from existing Alzheimer’s medications?

Other Alzheimer’s drugs may help alleviate symptoms of the disease, such as agitation and confusion, by altering brain chemicals. They are given as pills. The two anti-amyloid drugs are given by intravenous infusion.

3. How do they differ from each other?

Leqembi binds to small molecules of amyloid called amyloid protofibrils. Kisunla binds to the amyloid plaques themselves. “Whether these different binding targets are critical is not clear,” Budson says.

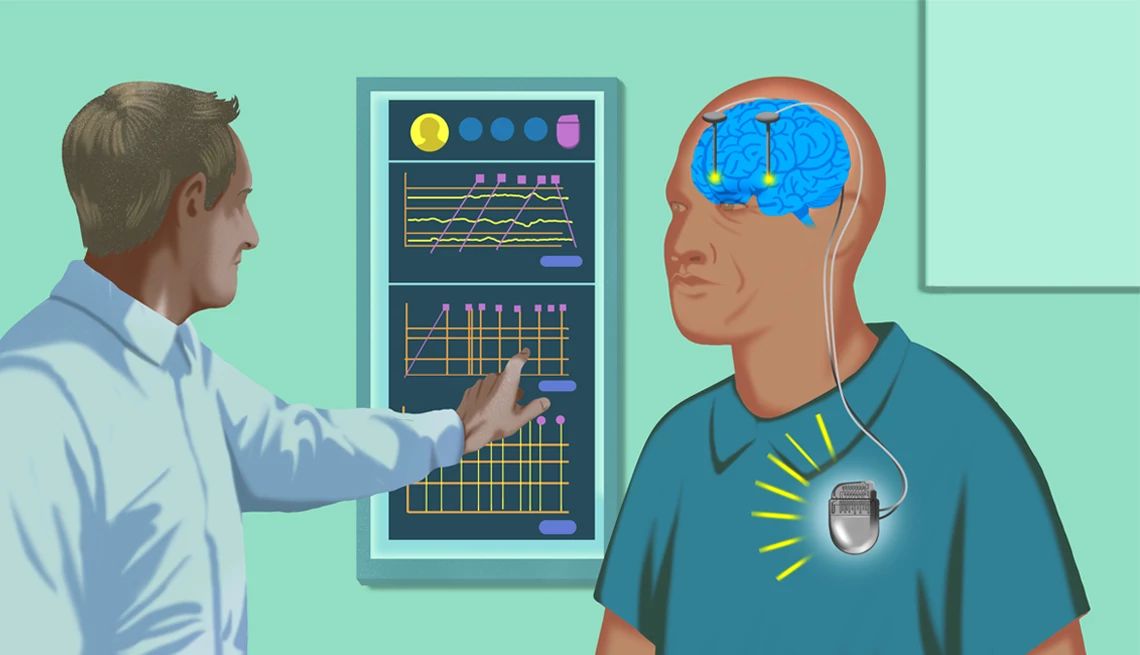

Leqembi is administered every two weeks for 18 months, then every two to four weeks after that, Budson says, adding: “There is no clear guidance on when to stop, if ever.” Kisunla is given every four weeks until the amyloid is cleared, as measured by a scan. If a PET scan shows minimal levels of amyloid, treatment is stopped.

In August 2025, the Food and Drug Administration approved a new maintenance version of Leqembi that patients can administer themselves at home. It’s a once-a-week single-use pen-like injection given under the skin. It can be used after patients complete their first 18 months of therapy.

“This weekly self-injection will certainly be easier for those patients who want to continue with lecanemab after the first 18 months,” Budson wrote in an email. “It should be noted, however, that donanemab (brand name Kisunla) can be stopped after the amyloid plaques are removed, and about 70 percent of people on donanemab reached this stopping point after 18 months.”

4. What are the side effects? Are they serious?

There can be drug reactions that resemble flu-like symptoms, such as chills, shortness of breath and rash, which are generally mild and treatable with over-the-counter acetaminophen and antihistamines, such as Benadryl, says Dr. Jason Karlawish, professor of geriatrics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and codirector of the Penn Memory Center.

)

)

More From AARP

How to Be a Caregiver for Someone With Dementia

It’s a tough job, but there may be more help than you think

Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias

Learn how to lower risk and get careDoes Medicare Cover Dementia Care?

Medicare covers tests and drugs, not custodial care

Recommended for You