AARP Hearing Center

For Deb Zeyen, Parkinson’s disease began as an unstoppable tremor in one finger.

She was in her early 60s, newly retired from her job as a marketing vice president for CBS Television in New York City and diving into new work protecting the environment on Mexico’s Baja California peninsula.

Over the next six years, her symptoms became increasingly severe.

“My speech slowed down, and my facial expression became blank. I felt endless fatigue,” Zeyen says.

She took a combination of levodopa and carbidopa to replenish dopamine, the brain chemical that diminishes in Parkinson’s. But she was plagued by the drug’s notorious side effect: uncontrollable jerking movements.

“I love snorkeling and scuba diving, but had to stop — I was swimming in circles,” says Zeyen, 78, who now lives in Berkeley, California. In 2021, she joined a study of an artificial intelligence-driven, nondrug treatment called adaptive deep brain stimulation.

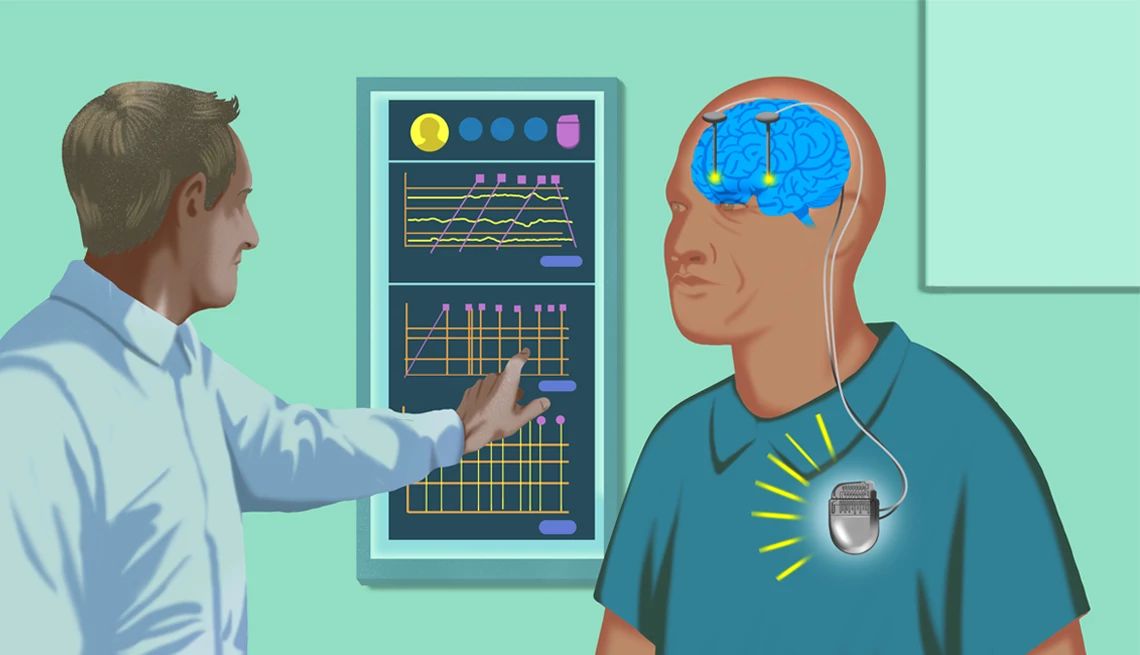

First implemented about 30 years ago, deep brain stimulation (DBS) helps regulate Parkinson’s symptoms by sending electrical pulses from a control unit implanted in the chest to electrodes in deep brain areas affected by the disease. But conventional DBS is capable of sending only one constant signal, which may be too weak at times to control severe symptoms and too strong at other times.

“Parkinson’s symptoms fluctuate over the day due to things like stress, fatigue and medications wearing off,” says Simon Little, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Adaptive DBS (aDBS), which Zeyen now uses, is designed to get around that problem. It’s an AI-enabled advancement that senses the user’s brain activity levels and dials brain stimulation up or down as needed. The first aDBS system, Percept from Medtronic, was approved by the FDA in February 2025.

Zeyen’s aDBS system was implanted in 2021 as part of a UCSF research trial. At first, it was set to conventional, continuous stimulation.

“My tremor stopped immediately,” she says.

Four months later, researchers at UCSF switched on the system’s adaptive software after training the controller on Zeyen’s brain-activity patterns. Electrodes could then sense Zeyen’s rising and falling brain activity and adjust electrical stimulation to match it.

)

)

You Might Also Like

AARP Smart Guide to Keeping Your Memory Sharp

22 science-backed ways to growing a healthier, happier brain, now and in the future

Doctor, My Partner Is Having Memory Problems

What to do if you think a loved one needs a cognitive test25 Great Ways to Cut Medical Bills

Get free health exams, spot billing errors, and other steps you can take