AARP Hearing Center

Would you want to live to 200?

The question sounds hypothetical. But thanks to a handful of scientific breakthroughs that have emerged in just the past two years, it might not be.

In 2023, Tony Wyss-Coray and his team at Stanford University were able to calculate the rate of aging of 11 major organs using proteins in the blood known as biomarkers. And this past July, researchers in Sweden announced they’d found that a simple blood test could detect Alzheimer’s disease with about 90 percent accuracy.

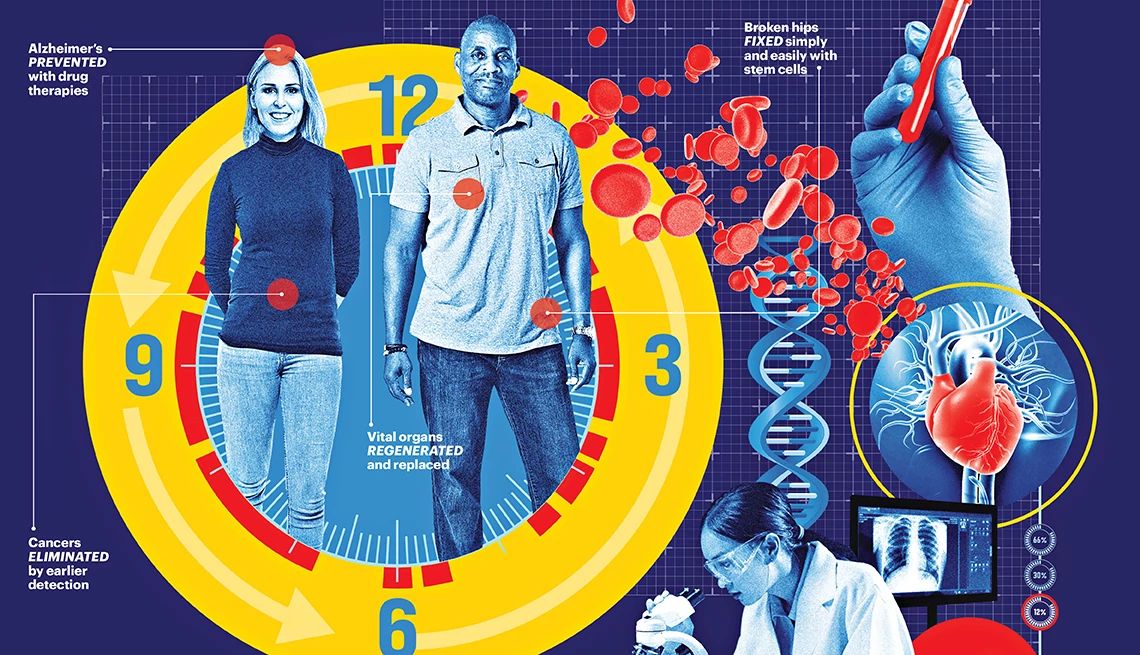

These discoveries have helped to create a new foundation upon which researchers can build, with the promise of detecting, treating and even halting emerging diseases— think heart disease, cognitive decline and many forms of cancer — before they have a chance to make us ill.

A mind-boggling tsunami of research is suddenly emerging from universities all over the world. In labs, old, frail mice that share blood with younger mice become healthier, stronger and live longer. Researchers believe this technology could one day be applied to humans. Such advances, which not too long ago were the domain of sci-fi novels and superhero movies, are now within sight.

Focusing on ‘health span,’ not lifespan

Today, the maximum human lifespan is estimated at somewhere between 115 and 120 years. (Frenchwoman Jeanne Calment, believed to be the oldest person who ever lived, died in 1997 at 122.) But researchers who study aging are no longer just focused on longevity. Instead, the end game is long life without many of the diseases that are associated with aging — not lifespan, but health span.

“We’re not looking to have people live forever,” says Thomas Rando, director of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center in Los Angeles. “We’re looking to have them lead healthy lives for as long as they live. That’s the dream.”

In their quest to improve health span, more researchers are studying the field of “super agers” — people over 80 whose memory is at least as good as those in their 50s and 60s. What separates these late-life high achievers from the average population? And how can the rest of us catch up?

“On average, individuals experience cognitive decline with each successive decade from our 30s and 40s onward,” says neuroscientist Emily Rogalski, director of the University of Chicago Healthy Aging & Alzheimer’s Research Care (HAARC) Center, who first defined the term super ager. “Identifying key factors that allow for youthful memory holds promise for helping others extend their health span and avoid Alzheimer’s and related dementias.”

Indeed, the biggest risk factor for chronic diseases such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, cancers, osteoarthritis — even hearing loss — is simply getting older. If we can slow the rate of aging, we can also delay, and perhaps prevent, the onset of disease, allowing people to live longer and healthier.

“We’ve identified some dials we can tweak that allow us to change the rate of aging,” says Eric Verdin, president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging.

“The hypothesis is not fully proven yet, but the evidence is pretty strong,” he says. “The aging field is transforming medicine.”

This new way of looking at disease has triggered a tectonic shift in the science of aging, a field of research referred to by a different name: geroscience. The goal of geroscience is to extend physical health and cognition and make being a super ager the rule, rather than the exception.

When it comes to aging, 'we need a radical new approach'

Preserving the health of people in their 80s, 90s and beyond is a critical challenge facing the U.S. Over the next 30 years, the number of centenarians in this country is projected to quadruple to roughly 422,000 by 2054, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, while the population of people over 65 may reach 82 million in the next 25 years.

“At least half of these individuals over 65 will have two or more diseases; a quarter of them will have three or more diseases by age 70,” says biochemist Laura Niedernhofer, director of the Institute on the Biology of Aging & Metabolism at the University of Minnesota. “We need a radical new approach.”

Some researchers believe the era of that radical new approach has already dawned.

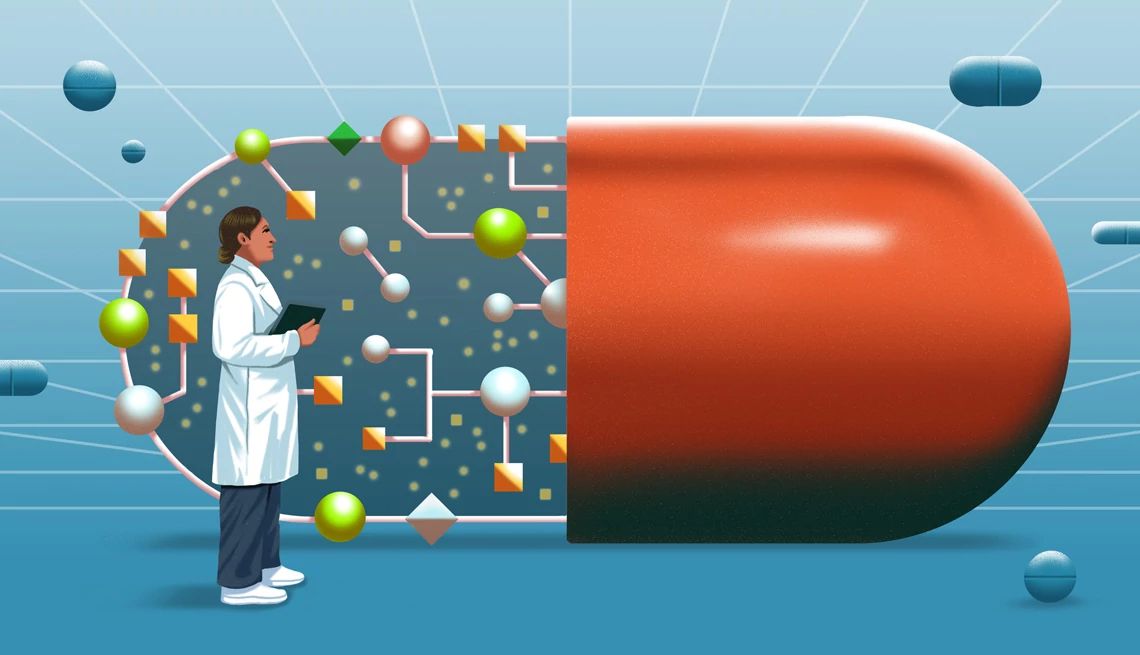

In the not-too-distant future, your doctor will be able to use antiaging supplements and drugs to “treat” aging overall, delaying the onset of age-related diseases. Advances in screening technology, together with targeted therapies, may usher in “a new era in the detection and treatment of cancer,” says Ronald DePinho, cancer biologist and the Harry Graves Burkhart III distinguished university chair and past president of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

In 10 years, for example, if you or a loved one is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer — which today has a five-year survival rate of just 13 percent — a combination of targeted therapy, immunotherapy drugs activating the immune system, and a personalized mRNA vaccine (which triggers a cancer-specific immune response) could lead to “doubling or tripling five-year survival,” DePinho says.

In 20 years, minimally invasive image-guided surgeries, followed by personalized vaccines after surgery, will help prevent recurrence of early-stage cancers.

In the coming decades, a hip fracture — which currently results in death in 21 percent of people 60 and older within a year after a fall — will be transformed from a potential tragedy into a temporary setback: Stem cell therapy, which may be delivered in a special infusion center, will allow older people to regrow bone mass, enabling them to return to full function and health, UCLA’s Rando says.

Your annual checkup will most likely be a lot different as well. Beyond basics such as glucose levels and triglycerides, the checkup of the future may consist of testing thousands of biomarkers — molecules found in your blood and other body fluids or tissues that can reveal potential or emerging diseases before they pose a threat.

Although biomarker-guided therapies have been used to treat cancer for decades, scientists are identifying biomarkers of aging that will help predict dementia, liver disease, osteoporosis and other diseases, allowing for earlier and more accurate interventions before disease sets in.

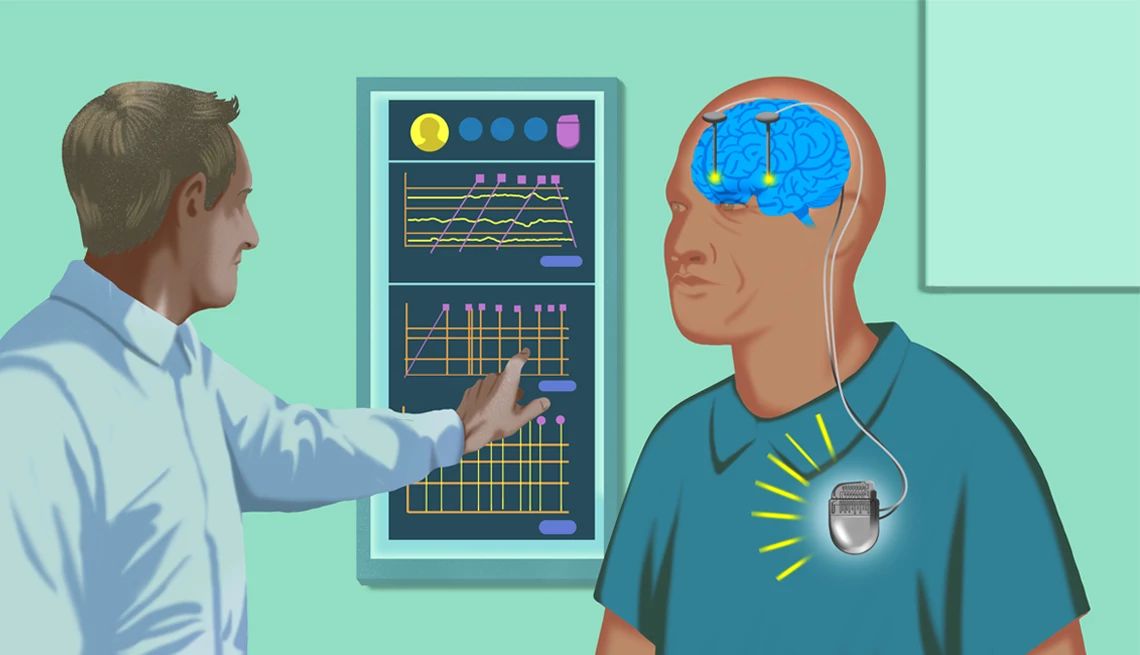

Some scientists, such as Harvard geneticist and longevity researcher David Sinclair, believe that aging can even be reversed. Here’s the theory: Day by day, year by year, our DNA replicates itself as we discard old cells and grow new ones. But like a copier running low on ink, the duplication gets less and less accurate, and genetic information is lost. That’s what creates aging.

What would happen if we could prevent that information loss?

Last year, in a paper published in Cell, Sinclair and his team made the case that a backup copy of the genetic instructions stored on the body’s “hard drive” could be rebooted, essentially reversing the damage done by aging. Though his experiments are primarily in the animal testing phase, Sinclair says he will start a trial next year to test this theory, with the specific goal of reversing blindness in humans.

)

)

You Might Also Like

How Do I Ask a Doctor for a Second Opinion?

Getting help when you're not sure that a diagnoses is right

What I've Gained From Taking a Weight Loss Drug

Shedding 40 pounds in a few months is just one plusThese Treatments Can Blast Your Wrinkles

The lowdown on 9 outpatient procedures to smooth and tighten skinRecommended for You