Staying Fit

Vincent DeVita Jr., M.D., was the medical branch chief of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) when Richard Nixon launched the “war on cancer” in December 1971.

“[T]he same kind of concentrated effort that split the atom and took man to the moon should be turned toward conquering this dread disease,” the president told a national TV audience, calling for an intensive $100 million quest for a cure that would be sparked by new legislation known as the National Cancer Act of 1971.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

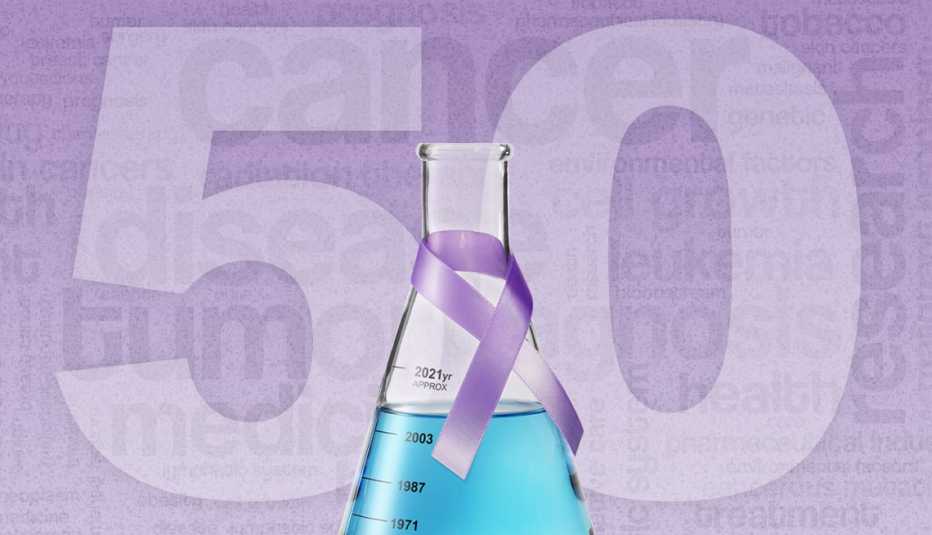

DeVita, who was 36 at the time, was skeptical. He has since changed his mind. “Money does buy ideas when you put brilliant scientists to work,” says the oncologist and researcher, who became director of the NCI from 1980 to 1988 and later director of the Yale Cancer Center. Today — 50 years and over $100 billion later — he believes that “we are not only winning the war on cancer, but the death of cancer is inevitable.”

Successes and challenges

Decisive victories abound. Since 1971, the cancer death rate is down more than 25 percent. Between 1975 and 2016, the five-year survival rate increased 36 percent. The arsenal of anticancer therapies has expanded more than tenfold. Mammograms, colonoscopies and other screenings are finding common cancers in early stages more often, when survival odds are as high as 99 percent.

Yet cancer remains the number 1 killer of Hispanic and Asian Americans, of women in their 50s and of everyone ages 60 to 80. Your lifetime risk for invasive cancer: a stunning 1 in 2 for men, 1 in 3 for women. And while it can strike at any time in our lives, cancer is now understood to be primarily a disease of aging, one that has proven more complicated than we ever imagined. While the root issue in all cancers is cells that mutate and grow uncontrollably, how this happens, the effects it has and how to treat it vary enormously, based on where in the body these cancerous cells occur.

“When the war on cancer started, somehow people thought we could do it in 10 years,” says oncologist Ezekiel Emanuel, M.D., vice provost for global initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania. “But going to the moon was easier. It takes a long time to understand complicated diseases.”

Here’s a look at where we stand.

Cancer, then and now

If you were diagnosed with cancer in the early 1970s, there was just a 50-50 chance you would survive the next five years. Your body — cancerous and healthy cells alike — would be bombarded with radiation, sliced apart in major and sometimes disfiguring surgeries and deluged with megadoses of highly toxic chemotherapy. And that’s if you were lucky. People considered “elderly” often got no treatment at all. Cancer was shrouded in terror and myth.

“People would whisper the word or call it the ‘Big C,’ like John Wayne did when he had lung cancer,” says Susan Leigh, an oncology nurse and a founding member of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS). “People would spray desks at work with Lysol because they thought that cancer was contagious. Families made a loved one with cancer use paper plates and plastic utensils.”

Plenty has changed, but plenty more needs to. Consider Leigh. Now 73, she’s a beneficiary of the war on cancer’s victories and has also weathered its shortcomings. A U.S. Army nurse who served in Vietnam, she was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1972. If untreated, her life expectancy was just three to five years. But radiation and a revolutionary multi-drug chemotherapy regimen called MOPP, developed by DeVita and considered one of the war on cancer’s earliest successes, put Leigh’s cancer in remission. The experience inspired her to become an advocate for cancer survivors.

“When I think back now on the war on cancer, the most important thing is that it increased funding for research,” she says. “But we thought in simplistic terms. Over 50 years, we’ve discovered cancer is not one but many, many hundreds of diseases. We’ll be looking for treatments for years.” Indeed, years after her early success, Leigh battled breast, lung and bladder cancer, as well as heart damage and weakened bones, issues that are often long-term side effects of both radiation and chemotherapy.

More on Health

5 Steps to Navigate the Cancer Caregiving Journey

Information and conversation are key to facing the challenges of care

5 Ways Cancer Care Will Change by 2030

Personalized therapies, new technologies to revolutionize treatment over next 10 years8 Symptoms of Colorectal Cancer

Plus, what you need to know about risk factors, treatments and the future of care