Staying Fit

When stocks collapsed in March, why were we surprised? Markets do that from time to time. This is the seventh crash I've covered as a journalist, not including several crashlets in between.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Emotionally, they've all affected investors the same way: Our breath shortens, our pulses race, and we kick ourselves for having been so optimistic about stocks the week before. Stress drives out rational thinking. We forget that, after crashes, it's too late to sell. That switching to CDs will lock in losses permanently. That the stock market, on average, has always — always! — recovered and gone higher.

Often following crashes, we run after new investment ideas that we imagine will keep us safe the next time around. Usually they don't, because, to be perfectly blunt, stocks are never safe; they're not supposed to be. But something has changed since the turn of the century: Investors have migrated toward stock index funds. Used properly, these funds can see investors through the current crash and future ones with greater stability and confidence. Before I talk about why, let's take a trip down memory lane.

50 Years of Downs & Ups

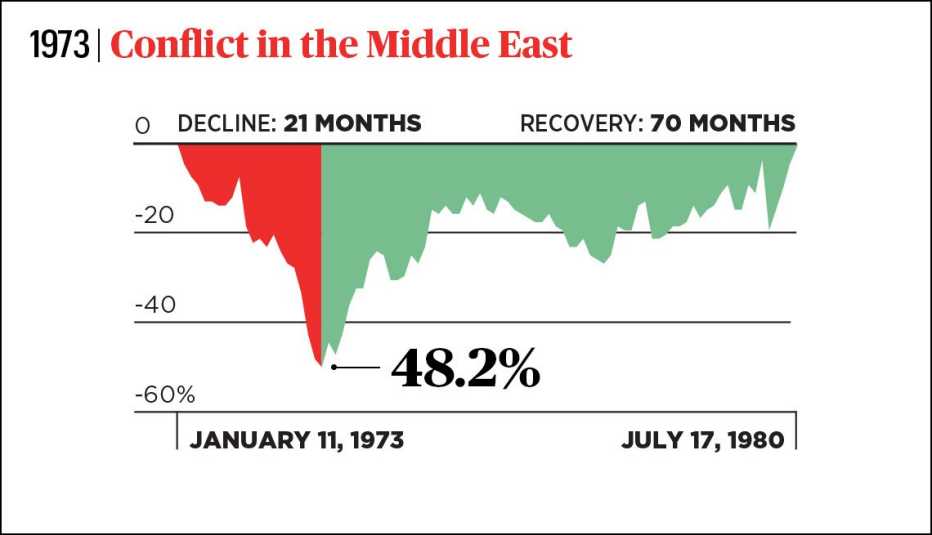

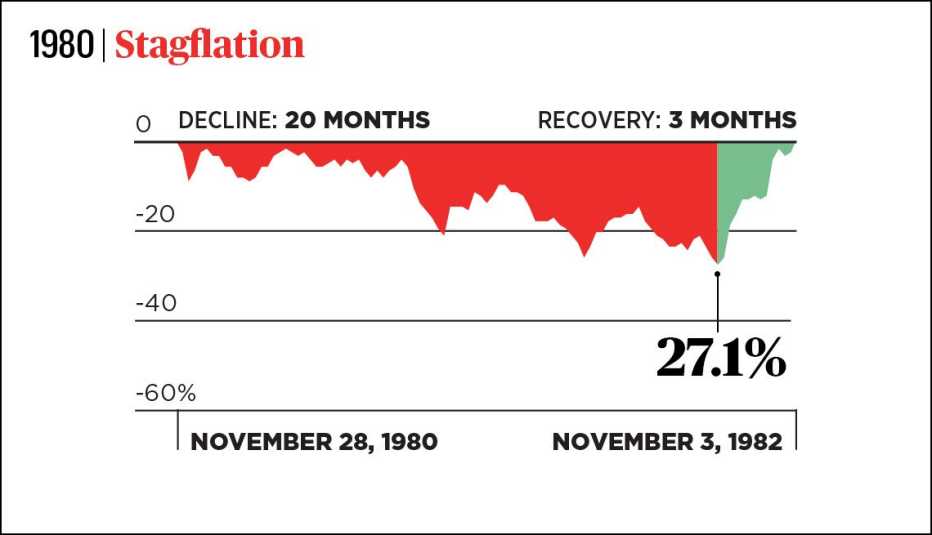

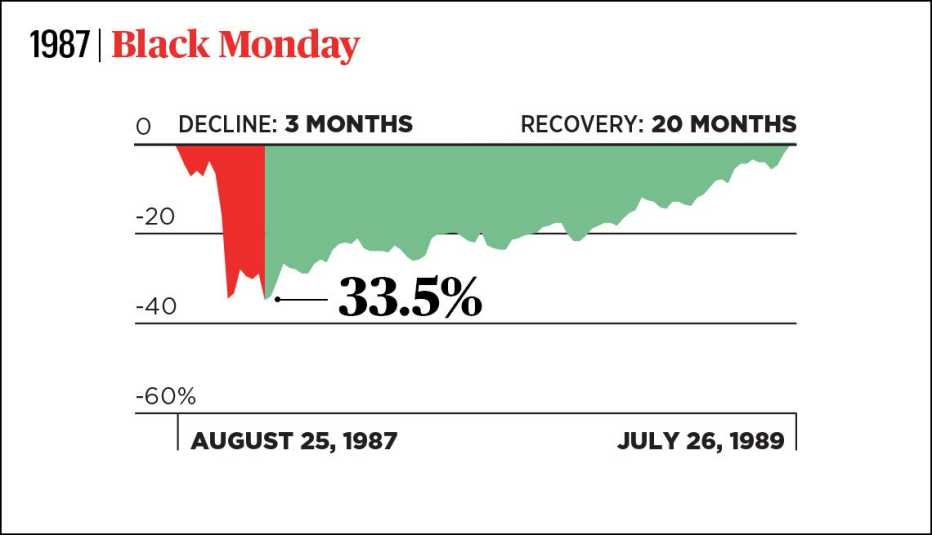

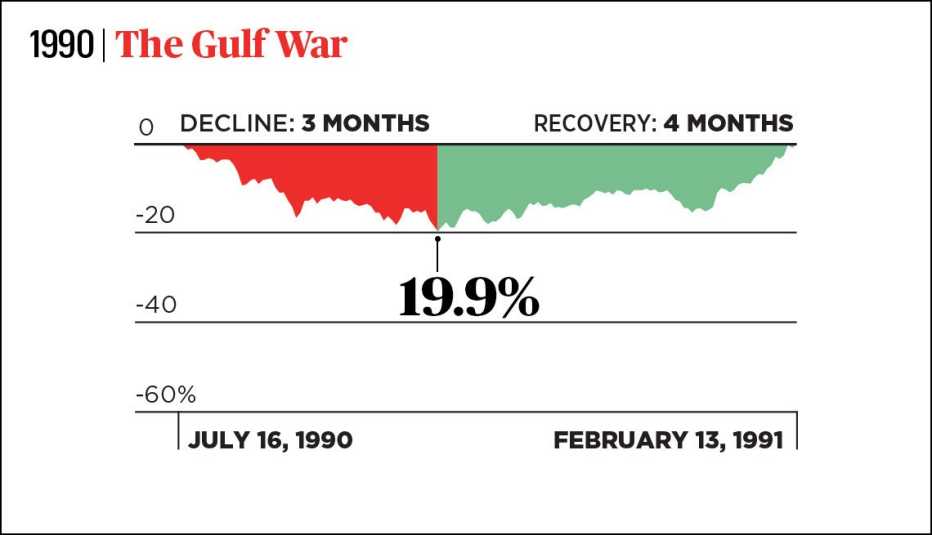

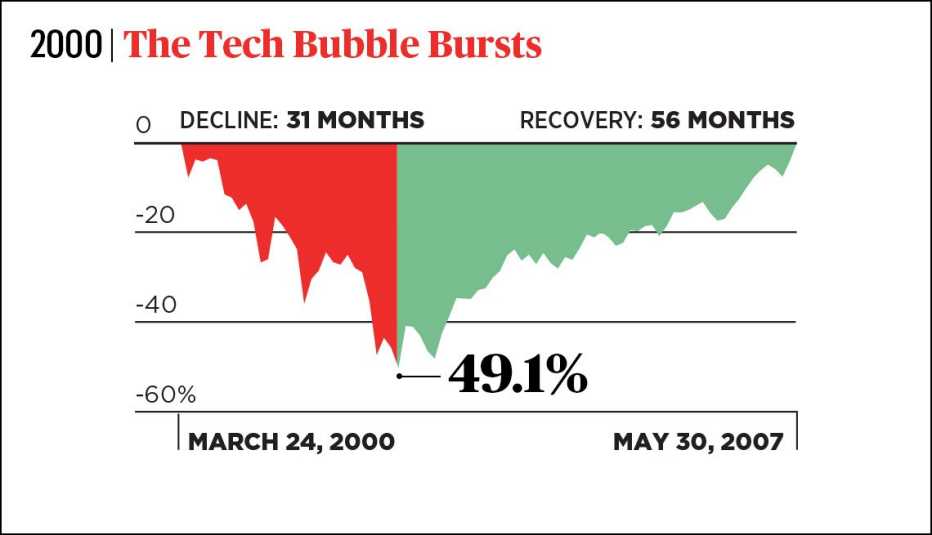

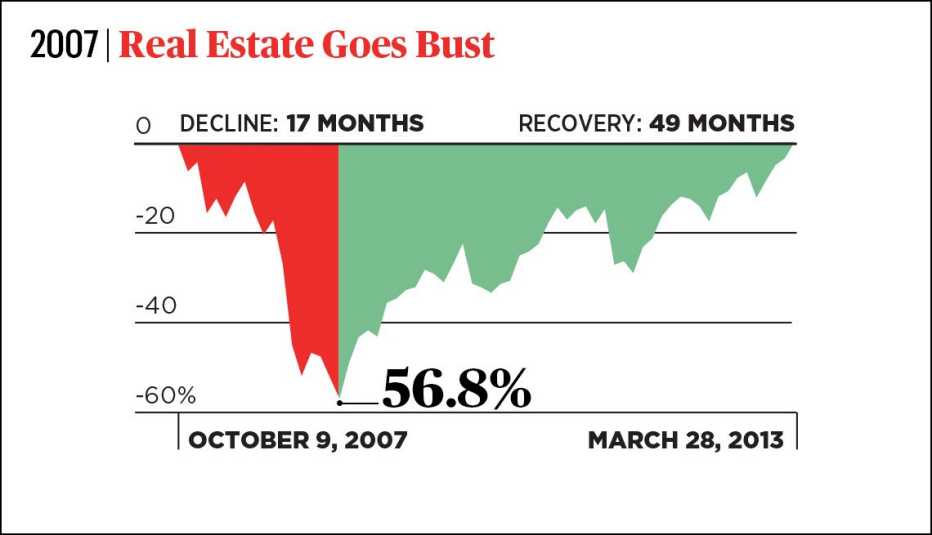

The S&P 500 Index — a common barometer of the U.S. stock market — fell 20 percent or more six times in the half century before 2020. Those bear markets, as they are typically known, averaged about 16 months.

I'll start with the Nifty Fifty of the 1960s and ‘70s. Those were 50 blue chip companies that supposedly could stand tall no matter how much you paid for shares in them. The market plunge of 1973-74 blew away that illusion. Stocks dropped 48 percent; most of the Nifties dropped further still. Some of them recovered, although at a slow pace. Investors’ infatuation with such once-mighty names as S. S. Kresge, Polaroid and Simplicity Pattern cooled.

In the 1980s, corporate raiders roared into town, carving up old-line companies to deliver “shareholder value” and hot takeover stocks. Chancy enterprises found financing for their corporate-makeover ambitions in the booming market for junk bonds. Math geeks dreamed up “portfolio insurance,” a computerized scheme supposedly guaranteed to keep money safe by selling at the first sign of a market drop.

Unfortunately, all the computers caught the sell sign at the same time. The result: Black Monday, October 19, 1987. Stocks fell 22.6 percent, still the largest one-day percentage drop ever. A friend on a coast-to-coast flight said his pilot announced the prices as they tanked. As usual, selling turned out to be a terrible idea.

More on money

What the 1929 Stock Market Crash Can Teach Investors, 90 Years Later

A lot has changed in 90 years, but stocks can still plunge8 Financial Experts on Surviving This Volatile Economy

Take a long-term view on current conditionsKey Terms for Investors Today

A primer for news in a volatile market