AARP Hearing Center

It all began around two and a half years ago, when Larry Duncan lost his older sister to Alzheimer’s disease. Duncan, then 76, witnessed his sister gradually lose the ability to recognize the people around her. Then Duncan started to notice some of his sister’s symptoms in himself.

“I could be talking to someone face to face and then, all of a sudden, somewhere out of the blue, would start trying to think, What is their name?” Duncan recalls.

It didn’t end there. Duncan could no longer subtract 7 from 100. He’d grow irritated when trying to perform a complicated task, says his wife, Pam. “It got very frustrating,” he says. “The more I got frustrated, the worse it got.”

Duncan was eventually diagnosed with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Today, he no longer drives and still struggles to remember names. But he continues to help around the house and is treating his depression, eating a Mediterranean diet, socializing and golfing to help slow the progression of his diseases, his wife says.

The couple recently returned from a three-week European river cruise where their fellow travelers “probably didn’t even realize Larry has cognitive decline,” Pam Duncan says.

AARP Brain Health Resource Center

Find in-depth journalism and explainers on diseases of the brain — dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, mental-health topics. Learn about healthy habits that support memory and mental skills.

“As long as you continue to stimulate and move, you can continue to learn and to live,” she says.

What is vascular dementia?

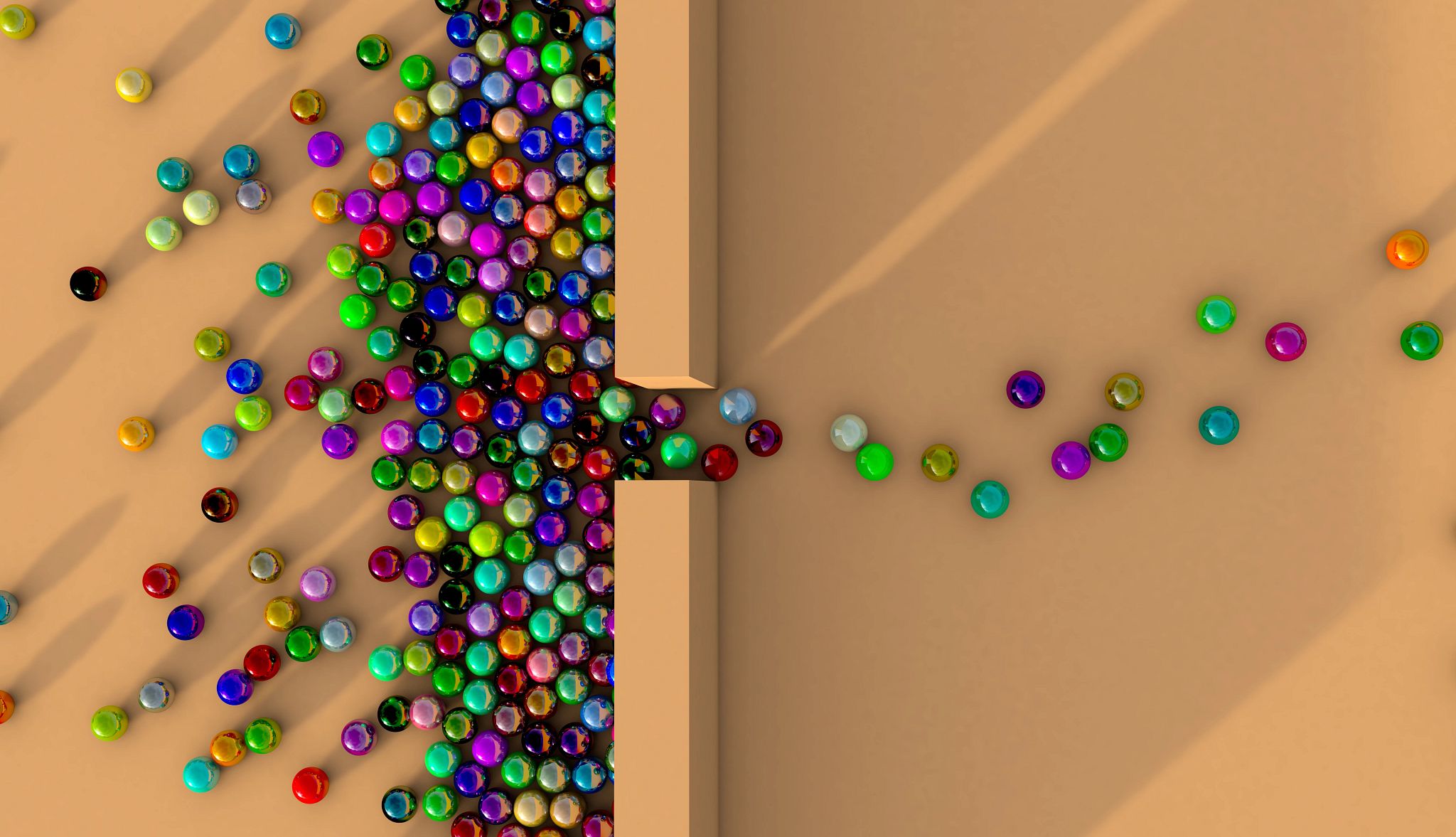

There are many causes of dementia. The most well-known is Alzheimer’s disease, in which brain cells are damaged by an accumulation of certain proteins in the brain. Vascular dementia, on the other hand, refers to a decline in thinking and motor skills caused by reduced blood flow to areas of the brain. The brain cells are then damaged by having less oxygen and fewer nutrients.

Damaged, shrunken or blocked blood vessels can all contribute to vascular dementia. Strokes are often a precursor to developing symptoms. Around 18 percent of people will develop dementia within a year of having a stroke, according to an analysis of 44 studies reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. High blood pressure is an important risk factor, as it can damage blood vessels in the brain. Essentially, “the things that are risk factors for heart disease and stroke are also the risk factors for vascular dementia,” says Anthony Levinson, M.D., a medical psychiatrist and researcher at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Other risk factors for vascular dementia include smoking, diabetes and high cholesterol.

More From AARP

Exercise Is Crucial for Parkinson's Disease

Regular exercise, the kind that gets the body moving and the heart pumping, can reduce symptom severity

What Are the Treatments for Stroke?

Learn about the various types of strokes and their treatments

Doctor, My Partner Is Having Memory Problems

What to do if you think a loved one needs a cognitive test