Staying Fit

Part I “Hey Jude”

In 2007, a young man named Colin Huggins began playing music on the streets of New York using a battered upright piano he’d bought on Craigslist.

He was a former accompanist for the American Ballet Theatre, but playing and singing pop songs outdoors had convinced him of the almost mystical power of music to soothe, delight and heal his fellow New Yorkers. He began to push the piano all over downtown, even managing to get it onto a subway platform at 14th Street.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

There, in December 2008, he was caught on a blurry cellphone video, later posted to YouTube, playing the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” In the course of two minutes, the potentially dangerous netherworld of the New York City subway — the very definition of existential alienation, where eye contact is assiduously avoided — was transformed into a place of joy, camaraderie, connection.

At first, four or five college-aged kids began to sing along (“take a sad song and make it better”), and by the time Huggins hit the crescendo (“better, better, BETTER”), a group of middle-aged businessmen in long black coats on the opposite platform were singing too. With the irresistible coda (“nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah-nah-nah-naaaah”), everyone on both platforms — male and female, Black and white, young and old — was singing, clapping, smiling at one another. The transformation was miraculous.

That video is testament to how melodies and lyrics lurk in our brains, ready to be released at the sound of a few notes — lifting our spirits, connecting us with our fellow human beings and evoking deeply buried memories as powerful as anything in the human experience.

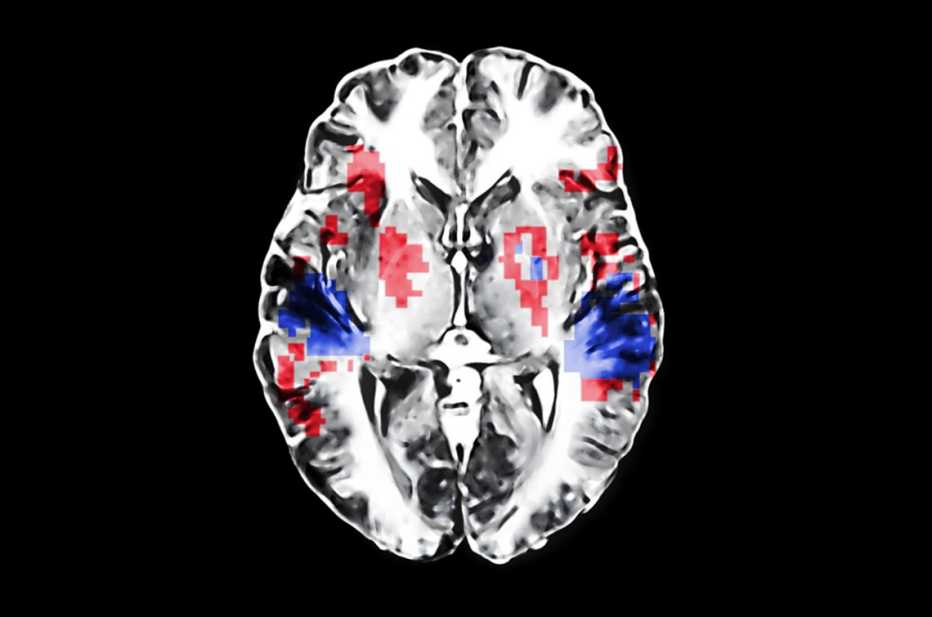

For more than 50 years, the medical specialty known as music therapy has harnessed this extraordinary aspect of music to treat diseases ranging from depression to chronic pain to movement disorders to autism to Alzheimer’s disease. But only in recent years has the scientific community begun to penetrate the mystery of how something as ephemeral as an acoustic signal — mere air vibrations — can have such profound effects on damaged bodies and brains. In the process, experts are gaining a deeper understanding of the importance of music in everyone’s day-to-day life, and its astonishing effects on the healthy, normal brain.

That music has been a part of human cultures since time immemorial is attested to by early man-made fossils — including various percussion instruments and a 60,000-year-old flute made from the femur of a now-extinct European bear — to say nothing of the original musical instrument, the human voice, whose remarkable music-making properties have given it a central place in virtually all forms of religious worship, from the chants of shamans in Indigenous tribes, to Islam’s haunting call to prayer, to the extraordinary overtone singing perfected by Buddhist monks in Tibet, to the hymns and psalms of Judaism and Christianity. According to historian of religion Karen Armstrong, “Scripture was usually sung, chanted or declaimed in a way that separated it from mundane speech, so that words — a product of the brain’s left hemisphere — were fused with the more indefinable emotions of the right.”

Recent scientific studies have shown that music’s power over us is not purely psychological but based in measurable physiological changes. Singing along with others to a beloved song (such as “Hey Jude”) causes the brain to secrete the chemical oxytocin, a naturally occurring hormone that creates the warm sensations of bonding, unity and security that make us feel all cuddly toward our children and others we love; infuses us with feelings of spiritual awe; and can alleviate chronic pain or the debilitating sensations of anxiety or the isolation of autism. One area of medicine where the power of music has been particularly remarkable is in the treatment of the dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease, whose stubborn and terrible symptoms have been resistant to most forms of treatment.

Part II “Fly Me to the Moon”

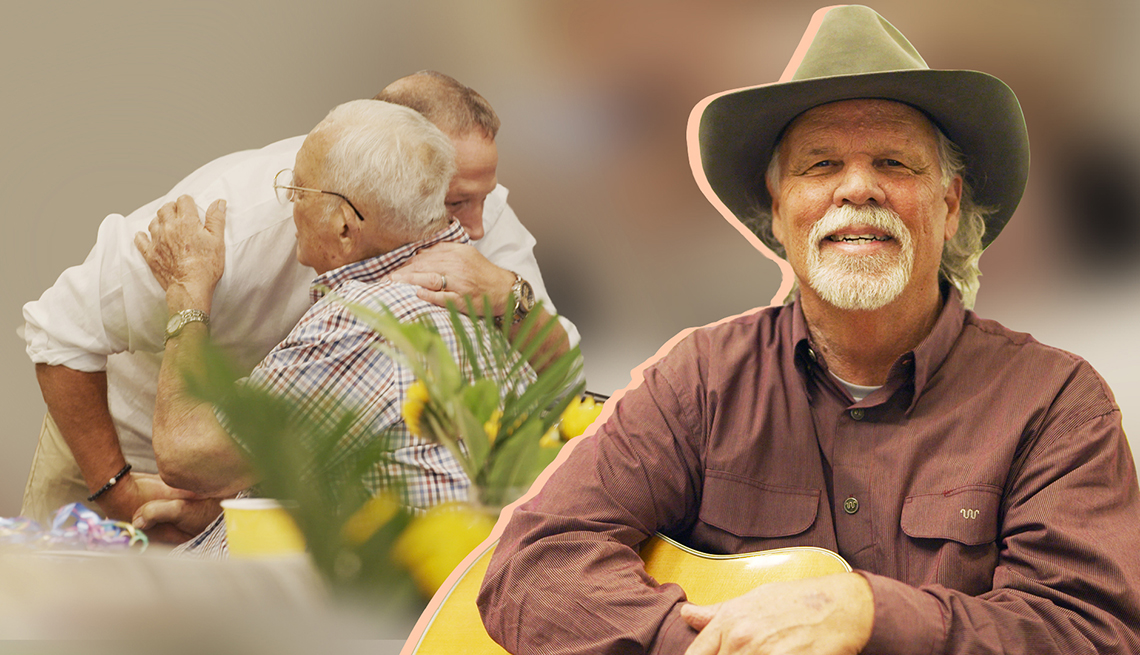

On a recent afternoon, I visited the 80th Street Residence, an assisted living community for dementia patients on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Seventeen patients gathered in a community room, and staff members helped seat them in chairs that faced the front of the room, where Xiyu Zhang, a 37-year-old music therapist, introduced herself to the group. Her audience stared back, blankly. (“They don’t all remember me,” she later told me. “They see me every two weeks, but many don’t know why I’m here.”)

She began strumming an acoustic guitar and singing: “Fly me to the moon / Let me play among the stars / Let me see what spring is like …” The effect was immediate. Chins lifted from chests, eyes opened. Smiles flickered on one or two faces. A woman began to sing certain phrases: “on Jupiter and Mars … in other words … hold my hand.”

Over the next 45 minutes, Zhang fanned the fragile spark of group attention into a steady blaze with a string of standards (“Blue Moon,” “Catch a Falling Star,” “You Are My Sunshine”) and got nearly every person singing along. Between verses, she called out questions: “Who sang ‘Singin’ in the Rain’?” A white-haired woman said, “Gene Kelly!” “What is the girl’s name in Wizard of Oz?” A woman in the second row blurted out, “Dorothy!” “And her dog?” “Toto!” “That’s amazing!” Zhang cried.

And it was amazing for people who, before the music started, would not have been able to recall the names of family members or the career they had pursued for 40 years — or been able to break free of the inward-turning silence in which the disease had wrapped them.

Indeed, isolation is one of the most frightening and unsettling symptoms of the memory loss that’s synonymous with Alzheimer’s and other dementias — a memory loss that separates a person from their very self. For what are we, ultimately, but the sum of our personal recollections? At the end of Zhang’s session, as the patients were led back to the elevators, the mood was a little like a bubbly cocktail party breaking up. Restored for the time being to a sense of self through the activation of better-preserved neural networks, the patients traded words and laughter with caregivers and one another — a transformation as miraculous as that of those commuters on the New York City subway platform. Indeed, more so.

Music therapy’s roots date back to World Wars I and II, when service members with traumatic brain injuries and “combat fatigue” (now called post-traumatic stress disorder) were discovered, by chance, to improve in mood and function when listening to music. Veterans hospitals began hiring musicians to play to patients, and it was not long before physicians realized that the treatment’s effectiveness would be enhanced if musicians learned the basic tenets of psychology, neurology and physiology, so that they could tailor their playing to a patient’s specific needs. Michigan State University launched the first degree program in music therapy in 1944.

Part III “Let Me Call You Sweetheart”

Concetta Tomaino was 24 years old in 1979 when she graduated with a master’s degree in music therapy from New York University. She would go on to become a pioneer in the use of music to treat dementia, and today, at 69, she is a legend in the field, the dedicatee of neurologist Oliver Sacks’ 2007 book Musicophilia, the past president of the American Association for Music Therapy, and the executive director and cofounder of the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function housed at Wartburg, a senior living facility in Mount Vernon, New York, where I recently visited her. Cheerful and soft-spoken, with a round face and curly brown hair, the Bronx-born Tomaino was, she says, “a big science kid.” But she also played accordion and trumpet. In college, she blended her loves of music and science when she decided to switch from premed to a degree in music therapy.

Tomaino was still a student intern in 1978, fulfilling the 1,200 hours of clinical fieldwork necessary for her master’s, when, at a nursing facility in Brooklyn, she encountered her first dementia patients — a population not then generally considered to be candidates for music therapy.

As was common in that era, the dementia patients were severely neglected: heavily drugged, hands encased in mittens to prevent their clawing at themselves, outfitted with nasal gastric tubes for feeding, and left to scream and wail in confusion and anxiety on an upper floor of the facility. “Nobody went up there,” Tomaino recalls. “It was this horrible, horrible place. The cacophony!” A nurse told her, “Oh, it’s so sweet of you to come, but they don’t have any brains left, so don’t expect too much.”

Tomaino refused to believe it. She lifted her accordion and started playing the opening chords of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” a hit tune published in 1910 that became even more popular when Bing Crosby recorded it twice, during the Depression and World War II.

She began to sing: “Let me call you sweetheart / I’m in love with you …”

“The noise stopped,” she remembers. “People opened their eyes. Half of them started singing along: ‘Let me hear you whisper / That you love me too.’ ”

More on Health

Celebrating What's Right With Aging: Inside the Minds of Super Agers

Some people in their 80s and 90s show shockingly little decline in their brainpower

How Excess Weight Affects the Brain

Those extra pounds can impact your brain health

Is it Normal Memory Loss or a Memory Problem?

Tips from experts on how to tell the difference