AARP Hearing Center

Fingerprints. Dog tags.

That’s how 1930s critics of the newly established Social Security system claimed the federal retirement benefit program would track American workers.

It was mostly political hyperbole. But devising an acceptable way of individually identifying the millions of workers who would pay into and, ultimately, collect Social Security proved a challenge so vast that even the man assigned to do it thought it was impossible.

Join Our Fight to Protect Social Security

You’ve worked hard and paid into Social Security with every paycheck. Here’s what you can do to help keep Social Security strong:

- Add your name and pledge to protect Social Security.

- Find out how AARP is fighting to keep Social Security strong.

- Get expert advice on Social Security benefits and answers to common questions.

- AARP is your fierce defender on the issues that matter to people 50-plus. Become a member or renew your membership today.

“No one in the world had ever done a huge task like this. They had to invent it as they went,” says Nancy Altman, president of the advocacy group Social Security Works and author of The Battle for Social Security, a history of the program. “The idea of enumerating that many people was a massive job. And they had to do it right away.”

The result was the nine-digit Social Security number, or SSN, an innovative solution so sturdy it has not only sustained the vast Social Security system but also spread to other government agencies and the private sector, becoming the de facto national ID.

“It was definitely ingenious,” says Rahul Telang, a professor of information systems at Carnegie Mellon University. “In a very simplistic way, they were able to come up with a number that was really robust.”

How this happened is a tale of political intrigue, bureaucratic dedication, a largely forgotten management consultant and a data file with the ominous name of Numident. It’s a story still being written, as the SSN’s evolution into the passkey to our financial lives makes it a potent tool for scammers and identity thieves that could eventually give way in some spheres to biometric identifiers such as … fingerprints.

Filibusters and ‘fearmongering’

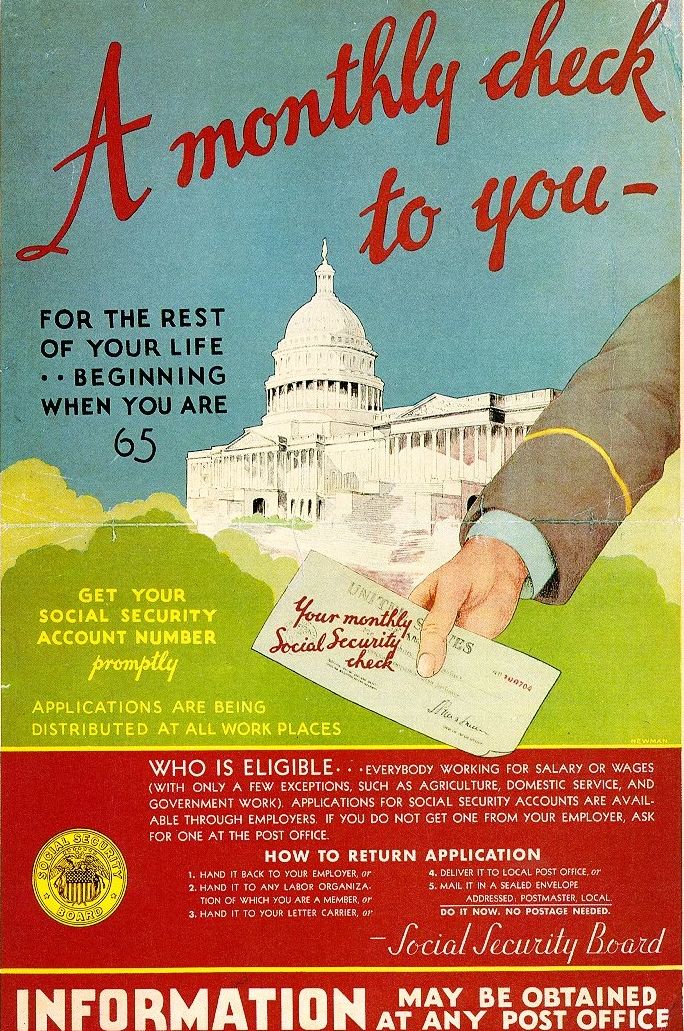

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act on August 14, 1935. The law set a January 1937 deadline to start collecting payroll taxes from the first 26 million workers covered by the program. That gave the Social Security Board — the precursor to today’s Social Security Administration (SSA) — less than a year and a half to hire thousands of employees, create a national network of offices and figure out the many details of the program from scratch.

Foremost among these was finding a way to accurately track people’s earnings across their working lives and store that information in a way that allowed fast, easy retrieval. That would require a universal form of identification, something Americans had never had.

The work was complicated by politics. A filibuster by populist Louisiana Sen. Huey Long blocked a budget bill that included start-up funds for Social Security. Roosevelt responded by shifting money and staff from other federal departments. Republicans, including Alf Landon, FDR’s opponent in the 1936 presidential race, stirred suspicions that Social Security would require workers to wear dog tags or be fingerprinted.

“It was fearmongering,” says Altman.

In truth, fingerprinting was considered but quickly shot down; while a few government agencies at the time used fingerprinting for ID purposes, Social Security officials feared it would make people feel like criminals. Simply using names and addresses was impractical in an era when more people shared the same conventional names.

According to Altman, the board calculated that there were hundreds of thousands of workers nationwide with common surnames such as Smith, Jones, Brown and Miller. “You’d need to know where all of these John Smiths worked, and every week you’d have to input what each of these John Smiths had earned,” she says.

A code of some kind would be needed. The first attempt was an eight-character string, three letters followed by five numbers, according to a 2009 SSA research paper on the process. This offered many hundreds of millions of potential combinations, but it had an important limitation: Few of the statistical machines then in use — essentially, analog computers that analyzed permutations of numbers — could process letters.

More From AARP

Why Social Security Is a Baby Name Influencer

Annual list associates the program with hot naming trends

These 7 Americans Depend on Social Security

Caregiving, health emergencies, business woes derailed their plans

How Social Security and Medicare Changed Aging

Historic programs transformed the financial and health care landscape for older Americans