Staying Fit

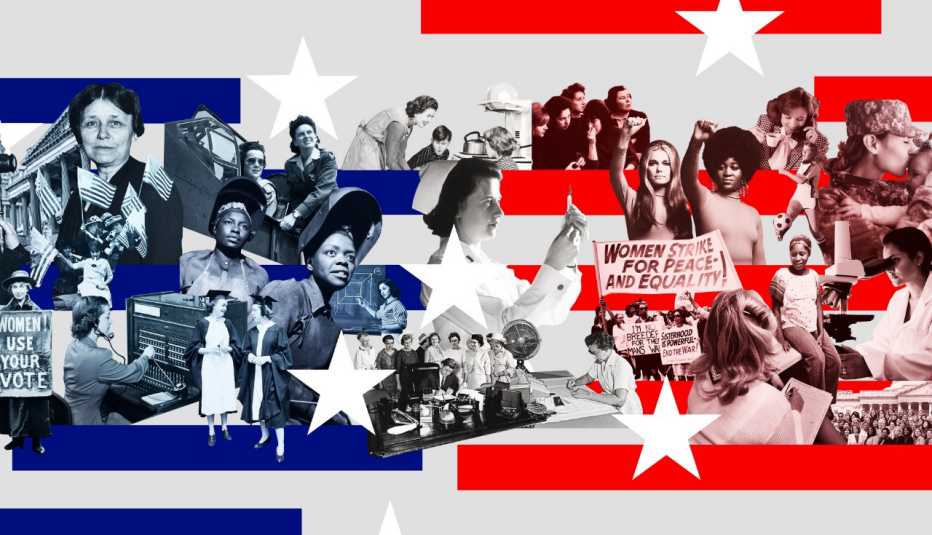

When suffragists won the right to vote 100 years ago, they thought full equality was right around the corner. They were wrong. And so, 50 years later, a second wave of feminism — embodied by a massive march in New York City — demonstrated for rights that were still being withheld: the right to get bank loans or hold credit cards without a man. The right to compete for traditionally male jobs and perform them without sexual discrimination or harassment. The right to plan their own families and craft personal lives in which they felt not only needed but fulfilled. Although the full equality that suffragists dreamed of has not yet arrived, women's personal and professional lives today have inevitably been influenced by this movement. To mark 100 years of the women's vote and 50 years of modern feminism, AARP interviewed three generations of women from families across the country. We wanted to know how their lives had changed, from decade to decade and from generation to generation. Though their stories are different, their message is the same: Women have more power than ever to live the lives they choose.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

A daughter lives her mother's professional dream

Mother: Mimi Nelson, 97, sculptor and retired social worker, Sherman, Connecticut

Daughter: Judi Weinstock, 70, obstetrician-gynecologist, Sherman, Connecticut

Granddaughter: Eva Gerard, 34, violist and music teacher, Brooklyn, New York

Mimi: From the time I was 5 years old, I wanted only one thing: to be a doctor. I would have gone to medical school, but there wasn't enough money. It was the height of the Depression.

Judi: Her father died when she was 15, and her mother didn't make enough money for tuition.

Mimi: It was a tremendous disappointment, because medicine captivated me. But there was also a gender expectation. When I was young, people would say, “Well, women don't do that.” And women just accepted it — no questions asked.

Judi: I probably thought about becoming a doctor because my mother was so invested in it. But even in the early 1970s, it was hard for a woman to get into medical school. Despite having good grades and putting out 26 applications, I wasn't accepted into any schools in the U.S. I ended up doing my first two years of med school in Mexico before transferring to Baylor College of Medicine in Texas and becoming an obstetrician and gynecologist. When I first started practicing, all my partners were men, and a number of patients didn't want to be seen by a woman. But times soon changed. Ten years later, everybody was calling my office. They only wanted to be seen by a woman.

Eva: I also have an interest in women's health. Being around my grandmother and mother, how could I not? But music won out.

Judi: My boomer generation was into all kinds of wide-ranging ideas and experiences. Today for my younger patients, it's more about achieving the perfect everything, from weddings to waistlines.

Eva: More is expected of women nowadays than ever before, especially in terms of motherhood. Today's mothers are expected to work, which is fantastic, but they're also expected to be there for their kids 100 percent of the time. There's so much pressure all the time. My grandmother told me, “You can't rely on other people to do things for you. You have to learn to do things yourself.” She gave the same advice to my mother, and that's why my mom can fix anything.

How partnerships have changed

Mother: Iris Sandler, 93, stay-at-home mother of four, Portland, Oregon

Daughter: Pat Sandler Welch, 70, staffing agency founder and CEO, mother of two, Portland, Oregon

Granddaughter: Brooke Welch, 43, laid-off art therapist, mother of one, Portland, Oregon

Iris: Honestly, I never wanted personal power. I wanted a man who would take everything over. I had that with my late husband, whom I loved very much. He had to work to make a living for us. I didn't work, and I didn't want to work. I defined myself as a wife and mother above all.

Pat: I think it's easier to access confidence and personal power now than in the past. When I was at home with my kids and not working, I thought I was kind of a B, B-minus mom. I was a much better mom when I was working, when I could really feel satisfied at the end of the day. Then I could come home and give all my attention to my kids. Of course, after my divorce from my children's father, staying home wasn't an option anymore. I was a single parent when I founded my staffing agency.

Brooke: Having a mother who was very driven and work-oriented was inspiring, but I'm not as driven in that way. I don't really believe in having it all. My daughter, Frankie, is 4, and I chose to stay at home with her for the first two and a half years. Then I went back to work part-time, which was good for me, a way to get back into my field. But I lost my position because of COVID-19.

Pat: After my dad died eight years ago, I asked my mother to move cross-country to live with me. It was really about her safety. But it turned out that I love having her live here. Brooke and her partner, Ryan, and Frankie have been living with us, too, which has been a delight.

Iris: I no longer have anxiety about getting the virus. I realize how old I am. One of my other daughters also lives nearby, and I'm enjoying my life with my kids and grandkids much more than I ever thought I would when I lived far away. I've loved being with them. We all have the same sense of humor.

Brooke: When I'm listening to my mom and my grandmother and thinking about my own experiences, I realize we all had different ideas about what we could expect from life. For my grandmother, I think she had this vision of what she wanted for her life, and she made exactly that happen. For my mom, I think she also had a vision of what she wanted — she married young, for love — then she adjusted based on her circumstances. She had her first child at 27, and I had mine at 38. I had already gone through my first big love, and I felt pretty pragmatic by the time I chose the partner I chose. I looked for someone who would be a good co-parent, who would be committed to me and to raising our family. I think I was a little more strategic than either my grandmother or my mother.

Pat: One of the lessons I got from my mother that I tried to pass on to my kids was that bad times will pass. When things were challenging or difficult in my life, my mother would say to me, “Pat, your life is a long book. This is but a chapter. You don't know the end of the story."

Balancing motherhood with ambition

Mother: Geneva Senior, 80, retired telecom specialist, mother of four, Hamden, Connecticut

Daughter: Darlene Winkler, 57, former Wall Street executive and leadership volunteer, mother of three, Roseland, New Jersey

Granddaughter: Sage Winkler, 26, accountant, Roseland, New Jersey

Geneva: When I was the mother of four young children, my husband worked and provided for the family, but he never helped out with domestic chores. Childcare and housework were things men did not do back then. I would cook before I left for work, and at night I would do the laundry and clean. I think it was even more difficult for women during my mother's generation. There were things she wanted to do in the world, but she wasn't allowed, either because she was a woman or because she was African American. It wasn't because she didn't have the ability. That was difficult for me to see; maybe that's one of the reasons I always told my children to shoot for the stars.

Darlene: Not only has my mother encouraged me to live my dreams, but she has also offered hands-on family support. I was able to move up the corporate ladder and accept positions that required long hours and global travel because I knew my mother and my husband would be there to help look after our three girls.

Sage: Both my grandma and my mom have made me feel like I could do anything. They've never offered me advice other than “Go for it.” Looking at their lives and what they've accomplished probably makes me push myself harder.

Darlene: There has definitely been a significant improvement in career opportunities for women since my mother was in the workforce. But to be honest, the change has not progressed as fast or as much for African American women as it has for white women.

Sage: I know that as a Black woman, there will always be certain challenges for me, no matter what year it is. That said, I definitely think I have more opportunities than my mom, and she had more opportunities than her mom. The internet and social media have created a more reachable world with more possibilities.

Learning to speak out against abuse

Mother: Fran Bull, 82, artist, gallery owner, professor of art, mother of three, Brandon, Vermont

Daughter: Katie Bull, 57, voice coach, jazz vocalist, composer, mother of two, Ulster County, New York

Granddaughter: Hannajane Bull Prichett, 25, artist, graduate student in geographic information systems and technology, Summit County, Colorado

Katie: I believe each generation is having a different experience of the #MeToo movement. And we have to listen to each other. I teach undergraduates, and I recognize how empowering it has been for young women to feel like they can talk about their experiences of harassment or assault and not be ashamed. And at the same time, it's a concern for me to see trial by the social media masses. I'm also the mother of a young man, so I know we need to make sure that when we're talking about freedom, that really what we're talking about is equality. We want to liberate women's voices by serving justice.

Hannajane: I have mixed views about it, too, but they're different ones. I think it's incredible that many women have come forward to speak about their abuse. But I also think it has put pressure on other women to go public. And it's a process, and I speak as someone who has been through it. Unfortunately, it took me many years to talk about it in any way. I have so much respect for people who are comfortable speaking about their experiences, but I also have as much respect for the people who are not there yet.

Fran: As a young woman, I accepted certain behaviors that women today are saying they won't put up with. I worked in the garment center in New York as a model, and oh, God, the harassment there was every day. The whole idea of beauty, I think, is an area that has not been explored, except maybe by philosophy. I believe there's a fear of feminine beauty. It can make a young woman a target.

Katie: My mom inspired me as an artist with her independence, passion, vision and dedication to her art. I think she is a genius, and not just because she's my mom.

Hannajane: Growing up, I was surrounded by strong female energy in every corner of my life — my mother and my two grandmothers. I was raised in a household where my opinion mattered, and having a mother who is a vocal coach taught me how to use my voice to assert myself.

Women who wanted more

Mother: Laura McKie, 84, retired museum education specialist, volunteer museum director, mother of two, Woodbridge, Virginia

Daughter: Deborah McKie, 59, college science instructor, mother of three, Manassas, Virginia

Daughter: Karin McKie, 56, educator, writer, publicist, actor, Chicago

Laura: When I went back to work in the early 1970s, nobody else that I knew was a working mother, but I was just going so crazy staying at home taking care of my kids.

Karin: We were some of the first latchkey kids in the neighborhood. She was a fantastic mom, but she said, “I've got a brain. I've got to keep my brain.” She started at the Smithsonian when I was in second grade and Deborah was in fifth grade. And it was fine. Mom always tells me that she felt guilty for leaving us with a babysitter, but we loved it, because we got a degree of freedom.

Laura: My husband, Alan, and I have been married for more than six decades. He has always been willing to let me do what I felt I needed to do. When I told him that I wanted to go back to work after the kids were born, he said, “Fine. We'll figure out a way to take care of the children."

Deborah: Women with families now are in a kind of “damned if you do, damned if you don't” position. If you decide to stay home with your kids — assuming you are financially able to do so — some working mothers look down on you. If you decide, instead, to keep working, some who stayed home will say that you are selfishly putting yourself first. Men are not faced with these choices. For that reason, I would say it is harder now than it was a generation ago, just because most mothers were not expected to have their own careers, so there was less pressure, even though there were also fewer choices.

Laura: After I retired from the Smithsonian, I got involved with an effort to create a museum in a former prison in honor of women who were imprisoned and tortured there in the 1910s for demanding the right to vote. I eventually became the director, and the Lucy Burns Museum opened at the beginning of 2020. The most compelling thing for me about the suffragists is the fact that these women were willing to die to get the vote. Literally. They went on hunger strikes with the understanding that they could die from not eating, and that they would suffer horribly from being force-fed by their captors. And yet they went ahead and did it. I mean, that kind of bravery is just beyond my comprehension.

Karin: We have all volunteered for the museum in various ways, including my dad.

Laura: He actually works for me now as a volunteer, giving tours of the museum to visitors.

Deborah: I think his greatest contribution to the museum has been his constant support and assistance to my mom, both mentally and physically. He brags about her all the time.

Climbing the ladder of success

Mother: Isidra Hernandez, 90, stay-at-home mother of nine, Houston

Daughter: Dolores Villarreal, 59, stay-at-home mother of four, Richmond, Texas

Granddaughter: Annette Silva, 31, TV producer, expecting her first child, Los Angeles

Dolores: In so many ways, I've had it easier than my mother. I was born here, so I grew up bilingual. She was born in Mexico and had to teach herself English. She got married at 15 and never finished high school. I graduated and did some college, and Annette has a college degree.

Isidra: I came to this country in my 20s, but I didn't become a citizen until 1980, because my husband didn't think it was important. The way I was raised, the man's word goes. So I waited patiently until he said, “OK, let's do it.” In the meantime, I worked on local campaigns, going door-to-door, supporting those candidates I believed in. When I finally cast my first vote, I felt like a giant—and I'm only 4 foot 10.

Annette: I've heard that my grandpa used to tell my mom and his other kids, “I want you to go work in the big, tall building and have executives as your bosses.” And I thought, Well, I don't have an executive as a boss. I am the executive. I've surpassed the ceiling of opportunity that my grandparents could envision for their kids. Here I am, working in the tall building, and my next thought is, I want to own the building.

Dolores: I used to doubt myself: How am I going to influence my girls to get educated, considering that I ended up getting married and dropping out of college? But they did finish. And now I'm almost 60, and I'm thinking it might be time for me to finish, too. I want to learn about computers and programs. There's a little hole in my soul that says, I really want this, and why not?

The feminine voice of farming

Mother: Colleen Loken, 78, grain farmer, mother of three, Owatonna, Minnesota

Daughter: Joan Maxwell, 55, dairy farmer, mother of three, Donahue, Iowa

Granddaughter: Kathrine Riffe, 32, federal farm program administrator, mother of one, Owatonna, Minnesota

Colleen: When my husband and I bought our farm 50 years ago, we had to purchase what we could afford. One of those things was a very old Hess tractor, which I loved to ride. I know this isn't very safety-conscious, but I'd drive with my little baby in a backpack and the other children hanging on the fender. I'd never get away with that now.

Joan: What I enjoy most about farming is the community. When somebody has a misfortune, the community is huge. I owned some farms near my parents’ land with my first husband, Gary, Kathrine's father. He was diagnosed with ALS in February of 2008, and we still decided to put the crop in. But it became apparent by June that he wasn't going to have the mobility to harvest. A farm friend of ours organized a crew. Everyone came together and took our harvest out in a day. After Gary died, in 2010, I met John, my second husband, and we have an educational dairy farm. Young people from all over the world come to learn American agriculture methods.

Kathrine: I loved growing up on a farm. Every day there was something exciting to explore or do. Who doesn't want to feed baby calves and take care of newly born chicks? I still enjoy working around my grandparents’ farm whenever I get the chance, even though now they only grow soybeans and corn.

Colleen: Back in my day, right or wrong, it was usually the man making the decisions about how to run the farm. My husband, Dale, and I were the exception. From the start of our 58-year marriage, we had a rule: First choose what's right for the family and then the rest will fall into place.

Joan: My mother's generation began to break the social rules. In my generation, we really pushed to get more equality in all areas of life, and that had an effect on farm life, too.

Kathrine: Agriculture is still a male-dominated field, though. In my 2010 class at South Dakota State University, there were about 60 students who graduated in agronomy, and only three of us were women. Many of the jobs in agronomy are essentially sales positions, and farmers have a hard time listening to what they consider a “little girl” trying to tell them what to do. But lately, I've seen a shift. Now there are more herds-women—people who take care of the genetics and breeding of large farm animals. Although I don't personally know any women who own and run a large farm on their own, I do see more women working side-by-side with their husbands. My daughter is only 7 months old now, but I would recommend farming to her when she grows up. Agriculture teaches you a lot, like responsibility and time management. It also points to the deeper aspects of life, because nature is right in front of you. It shows the way.

More on politics-society

Milestone Moments in Suffrage History

How women fought for the 19th Amendment and the right to voteBlack Women Had to Fight for the Right to Vote on Two Fronts

They were suffragists combating both racism and sexism long after the 19th Amendment was passed