Staying Fit

Sirens are warning of a coming recession. It's time for Americans to dust off their personal finance survival kits.

Recession red flags are increasing. The bond market, which has a reputation for sniffing out economic contractions, recently signaled that one is approaching.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

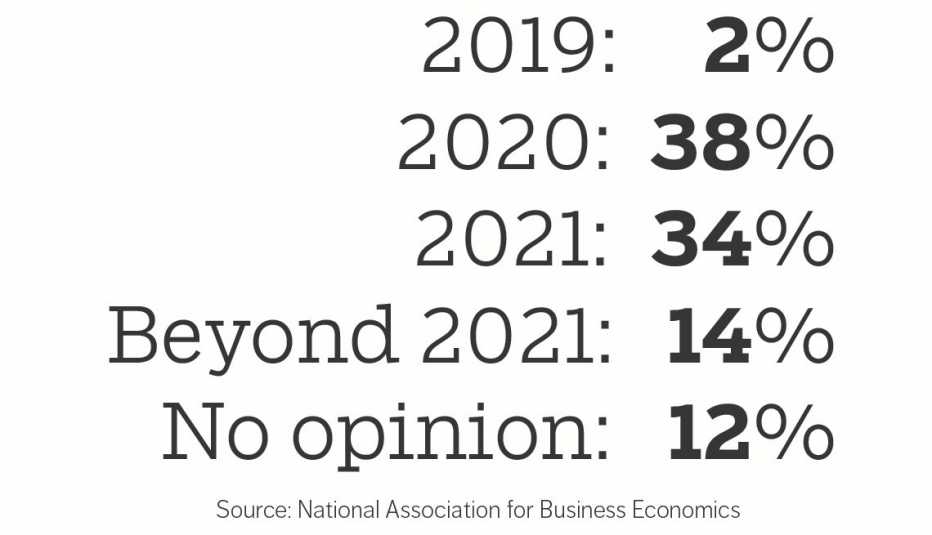

Nearly 4 of 10 economists polled recently said the United States will enter a recession next year, and 34 percent said the current decade-long expansion, the longest in history, will end in 2021. Global growth forecasts also are being trimmed as the U.S.-China trade war intensifies.

Are you prepared for tough times ahead?

Ten years after the Great Recession, the “R” word still strikes fear in most Americans. The dark side of downturns — layoffs, sinking stock markets, falling home prices — often expose financial frailties that can cause money problems for families.

But don't push the panic button just yet. Only 2 percent of economists polled expect a recession this year. That means it's not too late to “recession-proof” your finances before the inevitable downdraft.

"Now's the time to prepare,” says Jamie Cox, managing partner at Harris Financial Group. “Do it while markets are good, job prospects are fantastic and cash is rolling in.”

Here are five ways a recession could disrupt your life — and tips to cushion the blow.

Risk 1: Job layoff

When business slows and sales fall, companies look for ways to trim costs. That boosts the odds of layoffs, pay cuts or being forced into early retirement. It's harder to pay the bills without a paycheck.

"It's all about employment,” Cox says. “Once employment is affected, all the other financial components of your life are at risk."

Steps to take now. “Start thinking of plan B,” says Judith Ward, senior financial planner at T. Rowe Price. To boost your chances of getting rehired quickly if you're let go, update your resume, ramp up your networking and stay connected with work peers via social media.

Risk 2: Cash crunch

Not having a rainy day fund is risky. You can have no better protection against a recession than cash savings, especially if wages disappear.

You want to avoid raiding your 401(k), selling your investments in a down market or going into debt to make ends meet.