Staying Fit

Listen to chapters 7-12 narrated by Jack Holden, or scroll down to read the text.

Chapter Seven

JEN RAFFERTY WAS PANICKING. She’d hated this place from the moment they’d driven down the steep road into the village and now she was stuck here. There was a sense of helplessness, a lack of control that pressed too many buttons and reminded her of her old life. And then there were the kids, on their own at home. She went to the tiny room at the back of the pub that Harry Carter had prepared for her. She could lie in the single bed and touch both walls. It felt like a coffin. Outside, the battered fence banged relentlessly. She’d have to pull it down completely and stack it before bedtime, or there’d be no sleep at all.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

She phoned Ella but there was no response. The girl might still be on her way back from school. No point trying Ben. He never answered, so the next call was to Cynthia, her best friend and drinking companion.

‘Hiya!’ They’d had their bad times, but these days Cynth was always pleased to hear from her.

Jen explained where she was and what was happening.

‘No worries. I’ll pop in this evening and take in some food. I promise they won’t starve. And I’ll make sure they’re off to school in the morning. There was talk about the schools closing, but apparently the worst of the storm is supposed to pass through tonight.’

‘I have no idea how long I’ll be stranded here.’

‘I’ll keep an eye. Promise.’

So now, Jen Rafferty was out in the storm, knocking on doors. Usually, these interviews would be brief and conducted on the pavement, the questions routine, the canvassing a chore to finish as soon as was possible. Today, she accepted all the invitations to come inside, even those from people who had no specific information to share, but were curious, excited, anxious. She understood Venn’s priorities. He wouldn’t reject the gossip, the snippets of history. He’d embrace them. He always said that the police needed to know the community to understand individual offenders and victims. Besides, the freezing showers came suddenly, soaking her without warning, and the gale rattled around her head, making sensible thought impossible. There were no cups of tea because of the power cut, but the conversations in the warm tiny living rooms provided a welcome respite.

She started with Gwen Gregory’s immediate neighbour, a young mother named Katie Brennon who was at home with her toddler. The guard around the fire took up much of the room, and a wooden clothes horse with steaming baby clothes most of the rest. The child seemed happy to sit on the floor and play with coloured blocks. Neither of Jen’s kids had been that compliant.The woman seemed to appreciate the company.

‘Usually, I’d be out with the mums’ and babies’ group, but I couldn’t face it in this weather.’

‘Is it only mums? No dads?’ Jen couldn’t help herself.

The woman looked up sharply, suddenly defensive. ‘Oh yes, only mums. Fathers would be welcome, of course, but our men are all out working.’

And the women don’t work? But Jen let that go. Maybe she should have spent more time with the children when they were younger. Maybe she should give them more of her time now.

‘We’re just asking everyone if they noticed anything odd happening in the village last night. You’ll have heard about Jem Rosco’s murder.’ It wasn’t a question. Brian Branscombe’s team had already sealed off the top of the alley, and white-suited CSIs had made their way past the woman’s house, carrying their kit.

‘I didn’t see anything. The baby sleeps like a dream. She’s very content.’

Of course she is. Jen felt a moment of envy that was close to hatred. Her children hadn’t slept through the night until they’d started school.

‘And your husband?’

The woman stared into the fire and Jen had to wait for a response. Perhaps this wasn’t such a happy family after all.

‘He works from Bideford. But he does weird shifts, and he’s often late getting back. I was asleep when he got in.’

‘So, he might have been around in the early hours of today?’ Jen marked the man down for a follow-up.

‘I suppose.’

‘What work does he do?’

‘He’s an HGV driver.’ Katie looked up. ‘It’s important, keeps the country moving.’

‘Bit tough on families, though.’

‘Yeah,’ Katie said. ‘Sometimes it’s tough. But I’ve got family in the village. Loads of support. And Billy loves it.’

‘He’s back at work today? Even after finishing late last night?’

‘No, he’s still asleep. He had a nightmare drive back to the village.’ Katie looked up. ‘I’m not going to wake him. Not for a couple of hours at least.’

‘But you have no idea exactly what time he got in?’

She shook her head. ‘He’s very quiet. He doesn’t want to disturb us.’ A pause. ‘Nights when he’s that late, he sleeps in the spare room. I have Milly in with me.’

‘Very thoughtful.’

‘It’s a hard job. He needs his rest.’ Defensive again. Too defensive? Or was Jen being ultra-sensitive because her own husband had been a controlling bastard, too quick with his fists?

‘We’ll need to speak to him. When would be a good time to call round?’

‘I’m not sure.’ Now Katie looked directly at Jen. ‘He’s on a rest day tomorrow, even if the road’s open again, and he might want a couple of pints this evening. He’s had a heavy shift. He might not be at home.’

‘That’s okay then.’ Jen kept her voice easy. After all, another couple’s marriage was hardly her business unless it had a bearing on the investigation. Just because this woman had been on her own with the child and might fancy a bit of adult company, it wasn’t her place to comment. ‘We might catch up with him in the Maiden’s?’

‘Yeah. He’ll probably be there.’ Katie picked up her still silent daughter and stood up. An indication that it was time for Jen to leave.

+++

Until she reached the bottom of the hill, where the terrace joined the main road into the village, Jen had no more useful information. Most of the residents were elderly, cheery couples who were happy to talk and would have liked to help, but who had gone to bed early and drawn their curtains and bolted their doors against the wild weather.

‘This time of year, us don’t get out much.’ An old man with a walking frame seemed to speak for them all. ‘And us don’t see much either.’

The last house, the end terrace with a strip of grass to one side and a dormer showing a roof conversion, looked more promising. There was a child’s swing in the garden; concreted into the ground, the rope connected to the wooden seat, which was wrapped around one of the supports to stop it banging in the wind. Jen knocked on the door and a woman answered almost immediately. She looked to be in her early thirties and was wearing jeans and a sweater. Jen recognized her immediately as Mary Ford, the helm of the lifeboat.

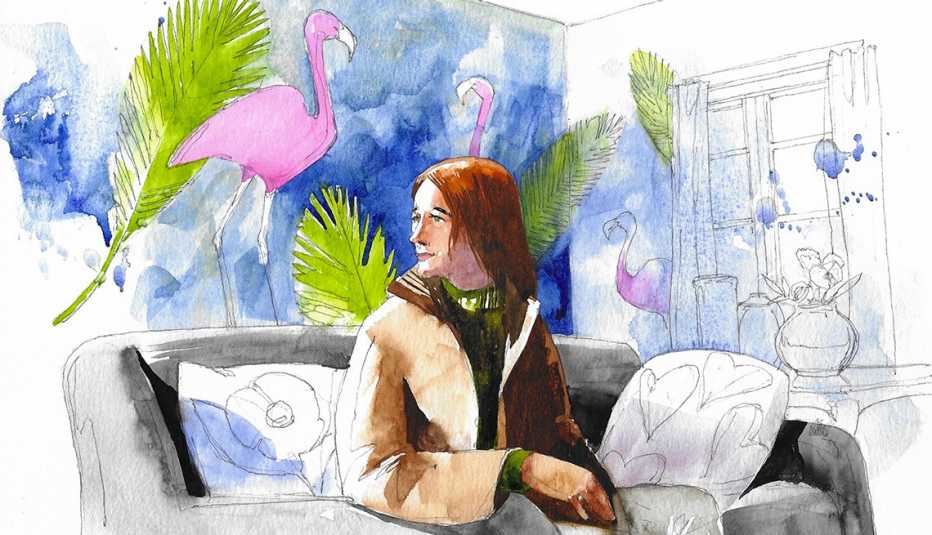

The interior of the house was as different from those belonging to the other terrace residents as it was possible to be. The ground floor had been knocked through to provide one space, the floorboards had been stripped and stained, and one wall had been covered with a flamboyant wallpaper depicting giant flamingos.The others were hung with paintings and prints.

‘Wow,’ Jen said.

‘Do you like it? I’m rather proud, myself.’ She nodded to the walls. ‘The prints are mine. The paintings have been done by friends.’

‘This is an arty community?’

The woman laughed so much that she almost choked. ‘You must be joking! No! But there are civilized hubs not very far away.’ She nodded for Jen to take a seat on a low grey sofa resting against the pink flamingo wall. ‘And honestly, that’s what I love about Greystone. The fact that it’s a working community. No pretension or bullshit. And, of course, the houses are very cheap. I wouldn’t have been able to afford anything anywhere else on the coast.’

It seemed that she had two kids in primary school – Isla and Arthur – and there was no partner on the scene. She earned a living from her woodcuts – she’d converted the loft into a studio – and from teaching a few hours a week in the high school in Morrisham.

‘You must be investigating Jem Rosco’s murder,’ Mary said then.

‘Did you know him? You said you recognized him when you pulled his body into the lifeboat.’

‘I met him once in the Maiden’s. Until recently, Lily, the old lady next door, has come in to babysit on Fridays to give me a night out. My dad stays over quite often now he’s on his own. I’ve been allowed into the ladies’ darts team.’

‘Allowed?’

Mary laughed again. ‘I’m not local, not born and bred here. Only inland from Morrisham, though to them it’s the end of the known universe. They’re not entirely sure I should be playing for Greystone. Or working in the lifeboat. But they know they wouldn’t win without me.’ She paused for a moment. ‘I had a real fan girl crush on Jem Rosco when I was a kid.’ Jen fancied that the woman was blushing. ‘I had posters of him on my bedroom walls, sent him endless letters asking for signed photos, or a chance to crew for him.’

‘Did he ever answer?’ Jen’s posters had been of boy bands and footie players. She couldn’t remember ever sending fan mail.

‘Nah. I guess every teenager who loved sailing sent him something similar, but he’d been to the same school as my dad, and he had a place in Morrisham, so I hoped for special treatment. I doubt any of them were read.’

‘You didn’t talk to him when you saw him in the pub?’

There was a moment’s hesitation, then Mary shook her head. ‘God, no! The embarrassment.’

‘We think Mr Rosco was killed in his own house late last night, or in the early hours of this morning. Did you see anything? A strange car or a person you didn’t recognize?’

‘I didn’t, but my father might have done. He’s staying for a few days. My son’s ill and Dad came across to give me support. It gives me some kind of life. To play the occasional game of darts.’ She paused and Jen waited for some explanation of the child’s illness, but the woman’s face only clouded for a moment, and when she spoke her voice was as cheery as before. ‘Dad’s upstairs having a rest; he doesn’t sleep too well at night and sometimes naps in the afternoon.’

‘Maybe I shouldn’t disturb him then.’

‘Oh, I’m sure he won’t mind. Since Mum died, he’s been bored. They used to travel a lot together, and he’s been at a loose end. He retired to lead wildlife trips around the world, but then Arthur got ill and he feels he should stick around to lend support.’

She left the room and returned almost immediately with a man in late middle age. He was tall, fit and wearing a sweater with a Devon Wildlife logo and jeans. Only his bare feet suggested that he’d been resting.

‘You’d heard that Jeremy Rosco was found dead this morning?’

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘Mary told me as soon as she got in. We had a late breakfast together once I took the kids to school.’

‘We think he might have been killed in the early hours of this morning. I don’t suppose you saw or heard anything unusual.’

Alan Ford sat in a small armchair, which had been upholstered in deep green velvet. ‘There was a car,’ he said. ‘It stopped at the bottom of the terrace and a woman got out, then the car drove off. I assumed it was a taxi, though I don’t think there was any sign on it.’

‘What time was that?’ Jen asked.

‘Late. The early hours of the morning. Past one o’clock because Radio 4 had finished and the World Service had started.’

Jen nodded, though she wasn’t entirely sure what that meant. Ella was a geek and listened to Radio 4. Jen liked her music, streamed it, danced around the kitchen to it.

‘Can you tell me anything about the woman?’

The man paused for a moment. ‘I didn’t see her face. There’s a street light at the end of the terrace, but I was looking down on the top of her head. She wasn’t dressed for the weather. Not for the rain at least. She was wearing a coat, very long – it almost reached the floor – and boots. Her hair was pale, nearly white in that light, and long enough to tuck into the collar of the coat. No hat.’

‘Wow!’ Jen was impressed by the detail.

‘Dad’s a naturalist.’ Mary sounded proud. ‘His specialism is damselflies and dragonflies. He’s used to recording detail.’

Alan Ford smiled. ‘I worked for the Devon Wildlife Trust for thirty years. I suppose noticing things has become a habit.’

‘Any colour on the coat?’

‘It’s hard to judge colour with street lighting, but I think dark green.’ He paused. ‘She was wearing a scarf, loose around her shoulders, wide, more like a shawl. I’m pretty sure that was green too, but it had flecks of gold thread in it. I could see it shining in the light.’

‘Did you see where she went?’

‘Of course! She’d caught my interest. She seemed an exotic creature to turn up in Greystone in the middle of the night. I was fascinated. She walked up the hill, up towards the top of the terrace, but from here I couldn’t tell how far she actually got, which house she went into.’

Jen thought she knew where the woman was headed, though. None of the other residents she’d spoken to had mentioned a visitor in the early hours. Most of them had been asleep for hours when this person climbed the hill. This must be Jem Rosco’s mysterious visitor. And if she’d arrived in a taxi, perhaps Gwen Gregory’s brother, Davy, might have more information about who she was, and where she’d come from. She felt the thrill of new information. This was why she loved this work; why she’d never have been able to give it up to spend more time with the kids.

‘The car,’ she said. ‘Any idea of the make? A colour?’

Alan shook his head. ‘I’m much better at identifying living creatures than machines. A lack of interest, I suppose, and my attention was drawn to the woman. It was a dark saloon. Grey or black. I can’t tell you any more than that.’

‘Which direction did it go when it drove off?’

He thought for a moment.

‘Towards the village. But then that was the way it was facing.

Even if it was heading back inland and up the main road out, it would be easier to drive down to the quay to turn round than do that here where the terrace is so narrow.’

‘If it had done that, it would have driven past your window. Did you see it? Hear it?’

Alan shook his head. ‘But then, I might not have done. Once the woman was out of view, I went back to bed, and I drifted very quickly off to sleep. A good night for me. I didn’t wake again until just before Mary came in to tell me that she was going out on the boat.’

Jen thought it would be pleasant to sit here, in this glorious space, and talk to the father and daughter, but she had to speak to Venn. In this house, she might have found their first positive lead.

Chapter Eight

ROSS MAY FOUND SAMMY Barton at home. He lived in a whitewashed cottage close to the quay, so near to the water that the spray must hit the windows at high tide. It wasn’t Ross’s idea of a perfect home; it was too wild, too insecure. Too close to nature. In summer, that smell of rotting seaweed must find its way in, and in this gale, it felt as if the whole building could be swept away at any time.

Inside, though, the place was tidy, civilized in contrast to the wildness outside. The man was sitting at a dining table at the front of the house, with a view of the sea, a laptop in front of him. His wife had opened the door to Ross, introduced herself as Jane, and had returned to a more comfortable chair by the fire. She’d picked up the knitting she must have been working on when he’d knocked. A paraffin lamp gave enough light for her to see what she was doing.

‘I’m just writing up this morning’s call-out,’ Barton said. ‘Though I’m not sure they’ll believe it in Poole.’ He looked up. ‘That’s where our HQ is based.’

‘Is it a full-time job? Working for the RNLI?’ Ross took a chair at the table opposite to Barton.

‘No! We’re all volunteers here. They have a couple of paid staff at HQ, but the rest of us do it for love. Because it could be one of our boys needing to be rescued.’

‘Sammy was helm for thirty years.’ The woman set down her knitting again and looked up, proud of her man. ‘He only stopped after the heart attack and that wasn’t his choice.’ She got to her feet. ‘Now I’ve finished this line, I’ll make some tea, shall I? We’re lucky we have a Raeburn in the kitchen and a load of logs that Sammy chopped from some pitch pine that washed up in the summer. Luckier than some in the village. I’ll make a pan of soup in a while and get it out to some of the older folk who have no power. You’ve got time for a cup of tea, Constable?’

‘I’d love one.’ The woman reminded Ross of his grandmother. As a small kid, he’d always been happier in his grandparents’ house than his own. His father had suffered from bouts of gloom, and had been a prickly bastard when the darkness hit. Depression, they might call it now. They’d probably have called it that then, if his dad had found the sense to ask anyone for help, or if Ross’s mother had shown any sympathy.

The woman went out and Barton switched off the laptop. ‘Best to save power though they seem to think we’ll be back tomorrow.’

‘What’s your regular job then?’ Ross suspected that Barton was retired. He’d hardly be sitting here in the middle of the afternoon if he was in full-time employment. But he knew too that people could be sensitive about stuff like that, and the man certainly didn’t quite look old enough to be getting a pension.

‘I do a bit of fishing in the summer. Lobster. Crab. The fancy restaurants round the coast will pay a good price.Tourists like the fact that they’re locally caught. The boat’s pulled up in the yard behind the house for the winter.’ He paused. ‘When I was still working full-time, it was more of a hobby, like. Now, it’s turned into a little business.’

‘What were you doing before?’

‘I was up at the quarry. Foreman. The last man standing when they decided to close it.’

‘That must have been a blow for the village. All those proper jobs lost.’ Ross’s dad had been in a proper job once. He’d been a serving policeman. Then he’d lost his nerve and ended up selling menswear in the only department store in Barnstaple. That had never seemed much of a real job for a man to Ross.

‘Ah,’ Barton said. ‘We could all see it was coming. The site nearly worked out and the transport costs so high. There was a bit of hope when they bought up Colin Gregory’s land, but it never came to anything.’

‘Did you know Jeremy Rosco?’ Ross thought it was time to get to the point. ‘Before he turned up in the pub a couple of weeks ago, I mean.’

Barton shook his head. ‘Only by reputation.’

‘You’ll have gone to the same school, though, if you grew up here.’

‘Only for a couple of years,’ Barton said. ‘Rosco was a bit younger than me, and you don’t mix much with the young kids, do you?’

‘I guess not.’ Ross paused for a moment. ‘What was he like at school? Did everyone think he’d end up being special? Famous, like?’ Oldham, the superintendent, would have thought a question like that was irrelevant, would even have mocked it, but Venn liked background, and Ross was starting to understand his way of working, and to appreciate it.

Barton took a while to answer. ‘Jem Rosco was always a good sailor. There was talk of him being in the Olympic team while he was still at school, but he never quite made it.’ There was another moment of silence. ‘He had a bit of a reputation as a cocky bastard. The staff would have loved it if he’d made the squad for the kudos of the school, but, secretly, I think the other kids were pleased when he missed out. They didn’t mind seeing him taken down a peg or two.’

‘Maybe they were just jealous that he was getting all the attention.’ Ross knew that he’d be jealous.

‘Perhaps you’re right. It’s a terrible thing, envy. It can eat away at you.’

Barton’s wife came in then with a tray. Tea in a pot. Chocolate biscuits on a plate printed with flowers, cups and saucers. Again, Ross was reminded of his gran.

‘Were you there when he turned up suddenly in the Maiden’s Prayer that first night?’

Silence.

‘We’re not really drinkers.’

Ross thought that wasn’t any kind of answer.

‘We go to the Maiden’s, though,’ Jane said. ‘Just for the company. It’s where the community gets together these days. It’s like a second home for the lifeboat crew. Nothing wrong with that.’

It seemed an odd response. A bit defensive. It reminded Ross of Matthew Venn when occasionally he came to the pub with the team after work. He always seemed a bit awkward there, never quite relaxed.

‘So, you were there that first night when Rosco came in?’

‘We were just on our way out, weren’t we, Sam?’ It was Jane again.

‘Yeah, we just crossed in the doorway,’ the man said.

‘Did you recognize him?’

‘I did,’ Jane said. ‘Not at first, but when he went inside and the light caught his face. I like those natural history programmes on the TV. But I didn’t say anything. Famous people must want to be private sometimes, don’t you think? They wouldn’t want to be bothered all the time by strangers.’

‘Did you see how he arrived? We can’t find a car.’

‘He was in Davy Gregory’s taxi.’ Still, Jane was the person to answer. Sammy Barton remained silent. ‘He’d already climbed out when we opened the pub door, but I saw it drive away.’

Ross thought this was a new piece of information, and his heart sang. He’d only just arrived on the scene and already he was making a difference. Ross saw this case as his opportunity to shine. His phone rang. He apologized and went outside to take the call. The wind blew his words away and he struggled to hear what was being said. He had to ask Venn to repeat his instructions.

‘One of Brian’s team is in Appledore to check out the dinghy where Rosco was found. It has a name on the side. Moon Crest. If you’re still with Barton, can you ask if he recognizes it? It might belong to one of the fishing boats based in Greystone.’

‘Sure.’

Ross opened the door to Barton’s cottage without knocking, and caught the couple in the middle of a conversation. They stopped talking immediately, as soon as he entered. He hadn’t made out any of the words, but sensed there’d been some disagreement. They stared at him awkwardly.

‘Is there anything else?’ Barton was gruff, almost to the point of rudeness. ‘I’ve spent all day on this.’

‘Just one more question.’ Ross kept his voice pleasant. ‘We’ve been looking at the dinghy where your crew found Rosco’s body. It’s called Moon Crest. The boss thinks it was the tender for a bigger boat. Does that mean anything to you?’

There was another moment of awkward silence. Jane looked at her husband.

‘That’s the name of my boat,’ Barton said at last. ‘She’s Moon Crest. But she’s been in the yard at the back of the house since I brought her in at the end of the summer.’

‘You have a tender?’ Ross asked.

Barton nodded. ‘In summer, I anchor Moon Crest out in the bay. Saves having to bring her ashore every time I go out. I use the tender to get to her.’

‘You haven’t missed it?’

Barton shook his head. ‘But then I haven’t looked. It’s under tarpaulin.’

‘We’d better go and look now then, hadn’t we?’

Barton didn’t speak. He pulled on the pair of wellingtons which were standing by the door and a yellow oilskin hung on a hook above them. He led Ross outside. The woman stayed where she was. There was an alley at the side of the house, wide enough for a car and trailer. Behind the house it widened into a yard, surrounded by a high wall. Ross could see the trailer out there, covered by flapping tarpaulin. Barton lifted a corner and Ross saw a white hull, a narrow deck leading down to a small cabin.

More From Anne Cleeves

‘The Long Call’

Book 1 in the Two Rivers series available free online

‘The Heron's Cry’

Book 2 in the Two Rivers series available free online

Short Story: ‘The Girls on the Shore’

Companion piece to ‘The Raging Storm’ available free online

A Chat With the Author

The best-selling British crime writer shares how ‘The Raging Storm’ differs from the first two books in the series