Staying Fit

Listen to chapters 13-18 narrated by Jack Holden, or scroll down to read the text.

Chapter Thirteen

MATTHEW AND JEN FOLLOWED the officer up the hill. Ross had wanted to come too. When Rainston had joined them, he’d been like an overexcited kid offered the prospect of a mound of sweets, ready to race ahead.

‘No need for us all to go,’ Venn had said. ‘We still have to consider Sammy Barton as a suspect. He’s got no motive that I can see, but all the opportunity in the world. And the best knowledge of the coast. You need to go back to his house at some point, Ross. Get a sample of soil from the yard where the dinghy had been kept, and from the garden. Also, a scraping from Barton’s boots.’ He’d sensed Ross was about to argue and went on before the man had a chance to speak. ‘Then give Brian a shout. He’s still at the murder scene. I need to know if they found any soil samples there. I didn’t see anything when I was in there, but I wasn’t looking and it wouldn’t take much for a comparison. They’ll be taking scrapings from the drainpipes.’ A pause. ‘Once that’s done, we’re still waiting on details of Rosco’s next of kin. I can’t believe he was completely alone in this world. Get on to it, will you?

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

He must have had some cash squirrelled away. Let’s see who inherits.’

Now, walking beside the local cop, who was beefy in build, but not as fit as he should be, still wheezing as they climbed the steep bank, Venn wondered why he hadn’t let Ross come along. Was it a kind of spite? He had taken a moment of pleasure in Ross’s disappointment. But, after all, a young detective needed to know that a murder investigation wasn’t all about dramatic revelations and murder weapons. It was about detail. And there was nothing a jury liked more than concrete forensic evidence. Jonathan always said Matthew overthought things, and perhaps that was true now as he analysed his response to the DC’s disappointment. Guilt lurked always, ready to pounce. Part of his own inheritance.

The three of them walked up Quarry Bank, past Gwen’s cottage, and past the cottage where Rosco had spent his last few weeks. That had been cordoned off from public gaze. The houses only ran on one side of the path; on the other was a strip of wasteland with a few scrubby bushes, a scattering of brambles. Venn saw that this had been the main area of search. Men and women were crouching, prodding the undergrowth. But Jimmy Rainston was still walking on up the footpath towards the quarry.

The boundary was marked by a rusting metal fence. There were holes in the wire, caused, Venn suspected, by local kids. He’d only learned as an adult that, to most teens, there was nothing as attractive as forbidden ground. He’d been a very different kind of teenager, a rule keeper, a little priggish. He’d probably have shopped anyone breaking through the fence to his parents or teachers. Jonathan would have been leading the fray with his bolt cutters.

Matthew wondered what that would be like: to be part of a gang of kids, released occasionally from parental authority, running wild, forming alliances with children different from himself, kids with different faiths or none. He struggled even to imagine it.

He was so lost in thought that when the policeman stopped at the fence, Matthew almost bumped into him. Beyond the boundary Venn could see a grey granite bowl of rock. A moonscape, pitted and uneven. The cheap set for a sci-fi movie. Large boulders littered the base and there were already saplings growing out of cracks in the cliff. Nature had started taking over what had once been a large industrial site. To one side, a piece of machinery had been left and had rusted so badly, corroded by salt and weather, that it was hard to guess what its function had once been. A group of white-suited officers stood in a group looking down at an object that was out of Venn’s line of sight. Venn heard footsteps behind him and turned to see Brian Branscombe.

‘They found our weapon then?’

‘Looks like it.’ Brian was local, and had a slow, careful voice and a very sharp wit. ‘I won’t go in. I’m still working on the scene in the house and the last thing you need is any sort of contamination for a defence lawyer to pick up on. There’s no rust, according to the boys, so it can’t have been there long and it’s the shape and size Sal Pengelly described when she first looked at the wound.’

‘Sal said it could be a kitchen knife,’ Jen said. ‘Wide bladed at the hilt but sharp. The sort a chef might use, but really anyone who liked cooking could have one.’

Venn turned to Branscombe. ‘Was it hidden?’

‘Nah, not really. It was lying on the ground behind a pile of rock. Not visible from this side of the boundary, but easy enough for the team to find once they’d started searching properly. Like I said, no rust or corrosion, so not left over from the time that the quarry was active.’

‘Could it have been thrown over the fence?’

Venn was trying to picture the scene. The killer would be left with a body in the early hours of the morning. They’d want to get it down to the tender. That at least had been planned. The quarry was in the opposite direction from the sea. He couldn’t see why someone would make even a short detour to dispose of the weapon.

But Branscombe shook his head. ‘You’d have to be a bloody good shot to get it that far. I think someone went in and left it inside.’

Why would you do that? The killer would have known it would be searched for and found. Easier, surely, just to leave it in Rosco’s bathroom? No effort had been made to hide the fact that it was the scene of the crime. Or if the knife was in any way distinctive, why not throw it into the sea while you were rowing out with the tender? It would be unlikely ever to be discovered then.

Again, Matthew thought this was staged in a childish sort of way. The killer was playing ridiculous games.

‘Did you find any soil in the house?’

‘DC May has just been in touch about that. There was nothing obvious in the bathroom, but we’ll be draining the plughole and taking samples from the stair carpet. Don’t hold your breath, though. Even if we find anything, we won’t get the analysis back immediately.’

‘You can get started on the stuff in the dinghy tender?’

Branscombe nodded. ‘Yeah, that’s already on its way to the lab.’

They watched him walk back towards the cottage crime scene, head bent, preoccupied.

Matthew stood for a moment, weighing priorities. The only person who’d been seen anywhere near Jem Rosco’s house at the time of the murder was Alan Ford’s mysterious woman. He turned to Jen, who was fidgeting, waiting for him to move.

‘The school day finished at three fifteen. It’s not much after that. Let’s go and talk to Matilda Gregory. I don’t suppose she’ll leave immediately, so we should catch her.’

+++

When they arrived, however, it was clear that this wasn’t the end of a normal day. People of all ages were going towards the school, not walking away from it. It was a small building, dated, Matthew guessed, from the thirties, when the quarry would have been at its most productive. Four classrooms faced onto the playground. Bunting had been strung over the door and a poster, painted by a child in orange and yellow, announced the school’s autumn fayre.

‘What do you think?’ Matthew asked. ‘Shall we come back another day?’

‘Nah.’ Jen was already making her way to the queue by the door. ‘Bet there’s a cake stall, and it’ll be a good way to get the village on side.’

They paid the pound entrance fee and followed the flow of parents and grandparents into the school hall. Stalls had been set up round the walls. It was a cross between a jumble sale, a craft sale and a fairground, with a coconut shy, raffles and sales of bric-a-brac, jars of homemade jam and home bakes. More of the grotesque knitted animals. Matthew recognized some of the lifeboat crew. Peter Smale and Harry Carter were manning stalls. Gwen Gregory was serving teas in one corner.

The conversation dropped a little when the detectives walked in and there were stares, not of hostility exactly, but wary curiosity. They could have been poisonous snakes in a zoo.

A woman moved towards a low stage at one end of the hall and called the room to order. Matthew recognized her from the photo he’d seen in the Ravenscroft farmhouse as Matilda Gregory.

She had a singer’s voice, deep and smooth, with a hint of a local accent. ‘Thank you so much to you all for coming. And to our children for all their hard work. I’m sure you’ll agree that the hall looks magnificent. This year, we’re raising money for Artie’s Fund. So, dig deep, so we can send a very special pupil to America to make him better.’

There was a loud cheer. Matthew looked around but he couldn’t see Mary Ford or her son. Maybe the child wasn’t well enough to attend, or perhaps the woman would find the idea of the charity deeply embarrassing. He knew that he would.

Jen nudged him and pointed to a grey-haired man who’d just come through the door, pushing the small boy in his wheelchair. There was still no sign of his mother.

‘That’s Alan Ford.’

As they watched, a young girl, whom Matthew supposed to be Mary’s daughter, ran from behind a stall towards the man. Ford swung her into the air and made her giggle. Matthew had a jolting memory of his father doing exactly the same thing, of the world tilting, of feeling safe in his dad’s arms, of finding himself laughing. His father had never done anything like that when Matthew’s mother was around. She disapproved of what she called ‘silliness’, and Matthew’s dad had always acceded to her will, in her presence at least. These rare moments between father and son had been secretly shared and now that he was dead, they were treasured.

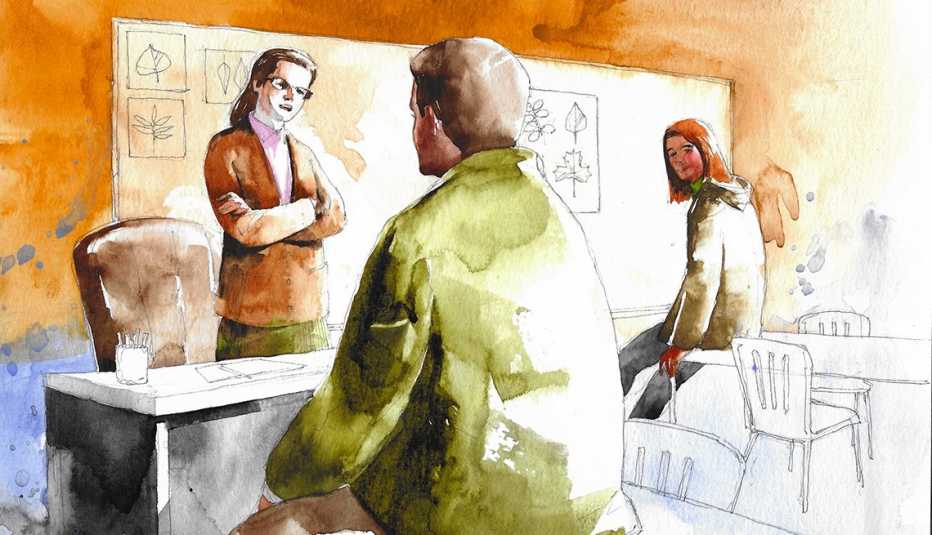

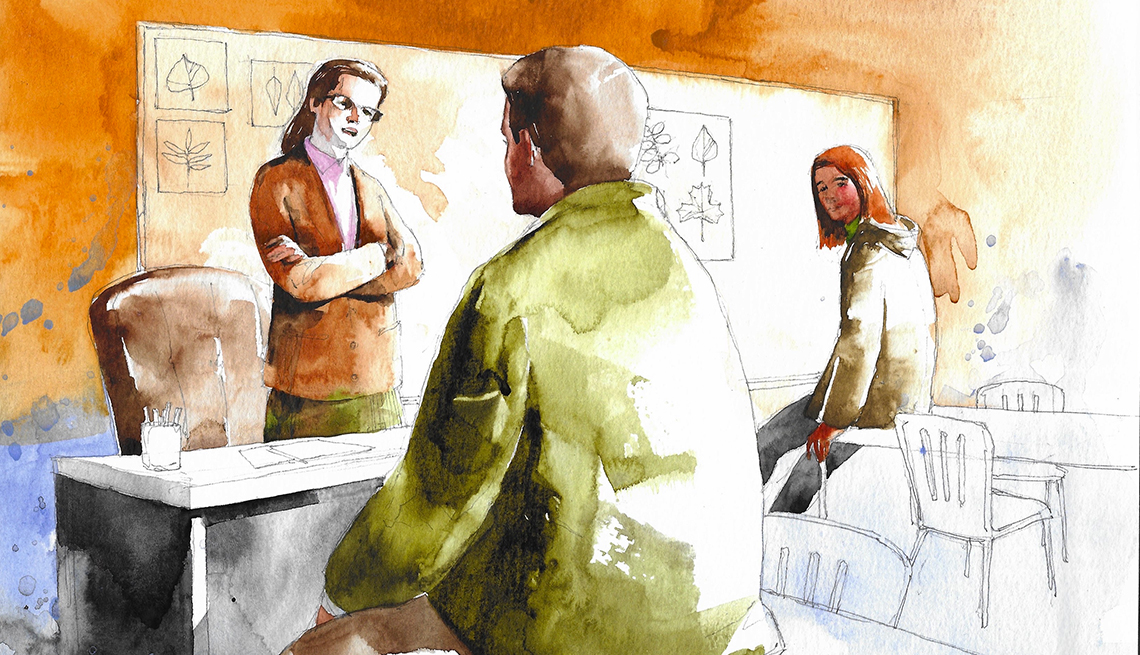

Matthew waited until the small crowd of parents around Matilda Gregory had dispersed, and then he approached her. She frowned, but led them out of the hall and into a classroom.

‘This really isn’t a good time. As you saw, I’m rather busy. We weren’t even sure we’d go ahead with the fayre until this morning.’

‘Because of Mr Rosco’s death?’ Jen asked.

The teacher looked up sharply. ‘No! Because of the power outage. They promised it would come back on today, but these things are never certain.’

She was wearing a long cord skirt and a rust-coloured cardigan, autumn colours, matched by the children’s art on the walls, a collection of collages made up of dried leaves and berries. Through the long windows there was a view of the grey sea.

Matthew introduced himself and Jen. ‘You’ll have heard that we’re investigating Jeremy Rosco’s killing.’

‘Of course. Davy phoned at lunchtime and said you’d been to the house to speak to him. I never met Mr Rosco in Greystone, though. I’m not sure how I can help.’ There was that frown again. An indication of things not being quite as they should be, or not as she would like them to be. Venn knew the feeling. He’d grown up with the Brethren too and understood their need for certainty, for unspoken rules to be kept.

‘We’re talking to most people in the village,’ Venn said easily. ‘It’s routine. The way we always work.’

She nodded as if she could accept the need for the routine. ‘Just a few questions.’

They sat on the children’s tables, rather than the chairs, but still Venn felt uncomfortable, undignified, too close to the ground. Matilda Gregory had a proper grown-up chair at the front of the class. She was wearing brown leather ankle boots with a small heel and she crossed her feet. Everything about her was modest, but she managed to look stylish.

As they’d decided, Jen took the lead. ‘Could you tell us where you were in the early hours of yesterday morning, Mrs Gregory?’

‘Is that when Mr Rosco was killed?’

Venn expected an evasive response, but Jen answered. ‘We’re pretty sure that it was.’

‘I was fast asleep,’ Matilda said. ‘I’m not one for late nights, even at the weekend. Certainly not when there’s school the next day.’

‘You were at home in Ravenscroft?’

She shook her head. ‘Some friends had an emergency. Ruth and Peter Smale. Peter’s the doctor here. Ruth’s mother’s very ill and they were called to the hospital in Barnstaple. They asked me if I could babysit their daughters in the old rectory in Willington. It’s only just down the road from us, but I wasn’t sure what time they’d get back, so I took an overnight bag.’

Venn thought that was something they could easily check. He made a mental note.

‘What time did they get back?’ Jen kept her voice easy, conversational.

‘Just after eleven. The crisis with Ruth’s mother had passed, so they felt able to leave her and come home. I was already on my way to bed, so I decided to stay.’

‘And you didn’t go out again?’

‘No! Of course not. What is this all about?’

‘A woman matching your description was seen getting out of a car at the bottom of the terrace where Mr Rosco was staying. Of course, your sister-in-law lives there too. Perhaps you were going to visit her?’

The teacher looked bewildered. ‘At that time in the morning? Why would I?’

Jen’s voice was gentle. ‘If Gwen was having a crisis of some sort? Surely you’d be one of the people she’d call? She has nobody else, does she?’

‘You think Gwen killed Rosco and called me to help her get rid of the body? That’s crazy, the stuff of horror films.’ She gave a little laugh. ‘Or comedies. You’ve talked to Gwen! She wouldn’t hurt a fly.’

‘Had you ever met Mr Rosco? Before he turned up here in Greystone?’

She was quiet for a moment. ‘Not that I remember,’ she said at last.

‘I’m sorry?’ Jen made it clear that she didn’t understand.

‘He knew my parents. Apparently, they were close when they were younger, all members of the Morrisham Yacht Club, but as far as I know, I never met him.’

‘He was at school with your husband. Yet you didn’t invite him to your house when he was in Greystone? Have him round to dinner to chat over old times?’

Watching, just out of Matilda’s sight line, Venn thought that was a great question. He wasn’t sure he’d have asked it in the same way. Jen was making a splendid job of the interview.

There was another silence. ‘We did invite him,’ the teacher said at last, ‘but he made excuses. He said he was expecting a visitor and he wasn’t sure when they’d turn up. He didn’t want to be too far from home when they arrived.’

Jen didn’t respond immediately and when she did her voice was a little firmer. ‘Just to be clear. You didn’t visit Mr Rosco in the early hours of yesterday morning? It seems such a coincidence, you see.You have a very striking appearance. It’s hard to believe that two women who look like you could be seen in the same place.’

Matilda looked up sharply. ‘I don’t lie, Sergeant. I think it’s a sin.Your witness is mistaken, or another woman who looked like me was there. Either explanation is more likely than that I’d be out on my own, visiting a man who’s not my husband, and that I’d lie about it.’ There was a moment of silence. Jen was hoping Matilda would say more, but in the end, she was the person to speak.

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Gregory. I don’t mean to upset you. I hope you understand why we have to check these things. A man has died.’

‘Of course.’ Matilda seemed a little more relaxed, even gave a smile. ‘And once the Smales got back from the hospital, they were in the house with me all evening.There were no mysterious disappearances. I can assure you of that.’

She got to her feet. ‘If that’s all, Detectives, I should get back to the fayre. The fundraising is important to us all in Greystone.’ When they didn’t immediately move, she stared down at them, the iciness returning. ‘I don’t know why you’re asking us all these questions. Mr Rosco only spent a few weeks here with us. Surely you should be asking the people he spent most time with: his family and close friends? They’ll be able to tell you more about him than we can.’

Jen glanced at Venn. He nodded his agreement that the interview was over, and they left together. Glancing back at the school as they passed through the gate, Matthew saw Matilda Gregory watching them through the classroom window, her phone to her ear.

Chapter Fourteen

AFTER THE BOSS AND Jen Rafferty left to talk to the teacher, instead of going straight to the Bartons’ cottage, Ross May headed back to the pub. A minor gesture of rebellion, to prove to himself that he couldn’t be pushed around. He’d try Barton later. He made an effort not to care, but he felt like the youngest in a family, always left behind, always treated like shit, never listened to. He worked harder than Jen – not surprising because he didn’t have the distraction of children – but Venn never seemed to notice. He and Mel intended to have kids sometime. Of course they did. But not until they’d established themselves in their careers and maybe not until they’d moved up the housing ladder a step. And then, Ross wouldn’t let kiddies get in the way of his work. It wasn’t his fault that Jen Rafferty had moved down here, leaving her husband behind. She’d chosen to be a single mother. Let her deal with it.

On the way, he phoned Brian Branscombe and received the information that the soil in the dinghy had already been sent to the lab and that nothing of interest had yet been found in Rosco’s bathroom. It would take time to collect all the samples, Branscombe said, implying that Ross should know that and was hassling him.

‘Sorry,’ Ross said. ‘The boss told me to ask.’ Let Venn take the crap.

There was a note on the door of the Maiden’s saying it would be closed all afternoon because of a community fundraising event. Ross had a key and let himself in. At least he’d be able to sit in the bar, instead of the poky room at the back. He set about struggling to get a handle on Rosco, to track down any recent contacts for him. There was a Facebook page, but that seemed to be professional rather than personal, and nothing had been added in the last six months. There were lots of photos of fancy yachts, gleaming in the sunlight against a backdrop of impossibly blue seas. Sailing porn. But few facts.

There was a phone contact for an agent, but when Ross phoned it, he was told that Jeremy Rosco was no longer a client.

‘Had he found a new agent? Could you give me the details?’

The voice at the other end of the line was frosty. ‘Mr Rosco decided that he could manage his own affairs. He resented paying our very reasonable commission.’ A pause. ‘He could be a little demanding. We weren’t sorry that he’d made the decision to go it alone.’

Ross was still working out the implication of that, and forming another question, when he saw that another call was coming through: his colleague Vicki. He apologized and told the agent that he might need to speak to her again.

Vicki had been helping with data collection in the station in Barnstaple and had found an address for the man: a flat in Morrisham. Once she had that, she’d traced his GP.

‘Not that it did much use,’ she told Ross. ‘Apparently Rosco hasn’t visited the doctor for at least five years.’

‘They’ll have a next of kin for him, though.’

‘Only an out of date one. An ex-wife. They divorced twenty-two years ago. She’s living in Barnstaple now.’ Vicki read out the address. ‘I asked someone to go round to inform her of Rosco’s death, but she’d already seen it on the news. Apparently, she wasn’t heartbroken.’

Left on his own in the Maiden’s Prayer, Ross tried to google Rosco again and came across an old episode of Desert Island Discs from Radio 4. Ross’s mother always listened to it while she was preparing Sunday dinner, so he knew the format. The adventurer was picking the eight records he’d want with him if he was stranded, and talking about his life. Ross thought much of the music was a bit boring. Though there was a bit of punk and some classic rock, it was mostly country. It was interesting, though, to hear the man talking about himself and his childhood, growing up on the North Devon coast.

‘I was an only child and my dad left when I was a baby. Probably just as well. He’d drunk himself to death by the time I was ten; they found his body in a hostel for the homeless in Plymouth. Yeah, it was tough growing up. My mother worked in a cafe – long hours in the summer and bugger all work in the winter. What you’d call a zero-hours contract these days. As a young teenager, I got into bother. Nothing serious. Mucking around. Always hyper, always wanting to be in on the action. Couldn’t see the point of school. It was the sea that saved me. There was a poster on the noticeboard in the classroom. Learn to Sail This Summer: hand-drawn pictures of dinghies in full sail. Turned out one of our teachers was into sailing. Suddenly, more than anything I wanted to be there, out in the bay with the wind in my face. I’d always been a water rat. I spent my days on the beach while my mother was working in the caff, looking for treasure on the tideline, poking around in the rockpools. I guess the club wanted some younger members, though I doubt they were expecting someone like me. I turned up to the yacht club with a couple of posh girls, and that was it. Love at first sight. With the sailing and with one of the girls.’ He gave a strange snort, which could have been regret. ‘I never looked back.’

The rest of the interview was about his success, the round-the-world record, his expeditions. But there was no explanation as to how he’d made the adventures happen. Ross couldn’t see how he’d turned from a schoolboy, crewing on other people’s boats, to a round-the-world yachtsman. A boat like that would cost a fortune, wouldn’t it? It would take sponsorship and Rosco wouldn’t have had those sorts of connections. They’d been told that the man had ambitions to sail in the Olympics, but he’d never made the team, and Ross couldn’t see how sponsors would be interested in ‘might have beens’. It could be worth a trip to the yacht club. Someone there might remember the real man, rather than the legend.

Then there was the posh girl who Rosco had fallen in love with. There’d been something in his voice as he’d spoken about her on the radio broadcast ... It was a leap, Ross knew that, but could she have been the mysterious woman the sailor had been waiting for? A romance from the past? His very first love?

He was still pondering this when Venn and Jen Rafferty came in, bringing a blast of cold air with them.

‘How did you get on with the teacher?’ Ross was about to ask if she was as glamorous as they’d been led to believe, then thought better of it. Neither Venn nor Rafferty had a sense of humour about stuff like that.

‘I’m not sure.’ Venn sat at the table. ‘She was very hard to read, and she was distracted. There was an event going on at the school. She claims that she was staying with friends on the night Rosco died.’

‘You didn’t believe her?’

Venn shrugged. ‘Not sure. The friends were in bed soon after eleven. We’ll have to check with them, of course, but she could have gone out again. Davy could have picked her up in his taxi. I can’t see why he would bring her into Greystone, if she and Rosco were having an affair? If she was his mysterious visitor. She might not be telling us everything she knows, but in an investigation, everyone’s got something to hide. It doesn’t mean she’s guilty of murder.’

‘Matilda Gregory said we should look into Rosco’s past for a motive,’ Jen said. ‘That makes sense, I suppose. As she pointed out, he was only here for a few weeks. But it did sound as if she was directing our attention away from the village. I wonder if it’s the community she’s trying to protect, not just herself.’

‘I have been doing a bit of digging into Rosco’s past,’ Ross said. ‘Vicki tracked down an address for his ex-wife.’ He’d been tempted to claim the discovery as his own, but Venn had a way of sniffing out that sort of deception. ‘They’ve been divorced for donkeys’ years, but she’s still living just outside Barnstaple.’

‘I could go and chat to her on my way home,’ Jen said. ‘At the very least she can give us some background, but she might have more recent information.’ A pause and a wry smile. ‘I suppose some divorced couples stay friends.’

‘I’ve had another idea too.’ Ross explained about the radio broadcast and Rosco’s early days of sailing. ‘I thought I’d visit the yacht club and see if anyone there remembers him and can explain how he funded his first trips. And he mentioned falling in love with a posh schoolgirl who learned to sail when he did. He comes across as a romantic sort of chap, doesn’t he? He might still have been holding a candle for her. I wondered if she could be the mysterious woman he was expecting to turn up at the cottage.’

‘Will anyone be at the sailing club?’ Venn sounded doubtful. ‘This sort of weather, nobody will be out in a boat.’

‘This time of year, it won’t be about the sailing.’ Ross was a member of the rugby club and, he thought, out of season, it wouldn’t be very different. ‘It’s more like a social club. Old guys sitting at the bar and chinwagging about past glories.’

Venn nodded.

‘I thought I might head out there this evening.’ Ross could see the prospect of an evening’s escape from this drab, depressing village. ‘It’s only a few miles away and I might turn up something.’

‘Sure,’ Venn said. ‘Good idea. Let’s catch up when you get back.’

+++

It was almost dark when Ross arrived in Morrisham, a stately town with wide, tree-lined streets leading to the waterfront, with its marina. This felt nothing like the North Devon Ross knew. It was genteel, with a faded grandeur, the main street flanked by a couple of large churches. Surrounded by gently rolling farmland, it had a vibe more reminiscent of the south of the county. Coaches full of elderly tourists regularly stopped here on their way to Torquay. There was one very grand hotel, with manicured lawns, and terraces where afternoon tea was served. The shops sold the sort of clothes his gran might have worn. He thought it must be a nightmare to be a teenager here. No wonder Rosco had been a bit wild.

The sailing club must have been built in the sixties or seventies. It was made of concrete and glass and looked down over the marina. Beyond it, a beach, backed by a wide promenade, led away into the distance. This, presumably, was where Rosco had gone beachcombing as a boy.

Ross May turned his vehicle into the club car park, and walked to the front of the building to get a sense of the place before going inside. Perhaps because the marina was so sheltered, some boats had been left there. The metal rigging sang in the breeze, a strange, slightly eery sound. The bar was at the top of the building and had a view of the water. The lights were on and Ross looked up to see couples sitting at the tables by the glass. The only young people in the place were the workers.

The door was at the back next to the car park, and was locked. It would take a code to get in. Ross pressed a buzzer, and waited.

‘Yes?’ The voice impatient and a little haughty. This wasn’t one of the young waiting staff.

Ross introduced himself. ‘It’s about the murder of Jeremy Rosco. I’d like to speak to anyone who knew him.’

A pause, a little laugh. ‘Oh, we all knew Jem Rosco. All the established members. He was quite a fixture when he was in town.’

The door clicked and Ross pushed it open. Inside, the lights must be operated by a sensor, because they suddenly switched on. There was a lift, a Perspex box, to carry the elderly or disabled to the first floor, and a set of varnished stairs, which Ross took. An overweight, florid man was waiting for him at the top. He held out a sun-spotted hand.

‘Barty Lawson. I’m commodore here. Come along in.’

He must have warned everyone in the bar of Ross’s arrival, because the whole room turned and stared, before pretending to be engrossed once again in their conversations. Now, it was quite dark outside, and Ross was mesmerized for a moment by the flashing buoys in the bay, and the sweep of the lighthouse beam from the headland beyond the beach.

‘Glorious, isn’t it?’ Lawson sounded as proud as if it were his personal property. ‘Takes a fortune in upkeep, of course. The salt wind eats away at the concrete. Now, what would you like to drink?’

Ross was tempted. Despite his swagger, he felt out of place in this sort of company, and a drink might relax him. But Venn had an uncanny way of sniffing out misdemeanours, and the breaking of rules.

‘Coffee,’ he said. ‘Thanks.’

Lawson ordered a coffee and a whisky from a middle-aged woman behind the bar, and led Ross to a table by the window. He must have been sitting there before Ross showed up, because a whisky glass, with a little left, remained on the table.

More From Ann Cleeves

‘The Long Call’

Book 1 in the Two Rivers series available free online

‘The Heron's Cry’

Book 2 in the Two Rivers series available free online

Short Story: ‘The Girls on the Shore’

Companion piece to ‘The Raging Storm’ available free online

A Chat With the Author

The best-selling British crime writer shares how ‘The Raging Storm’ differs from the first two books in the series