Staying Fit

5

Exactly Fifteen Miles an Hour

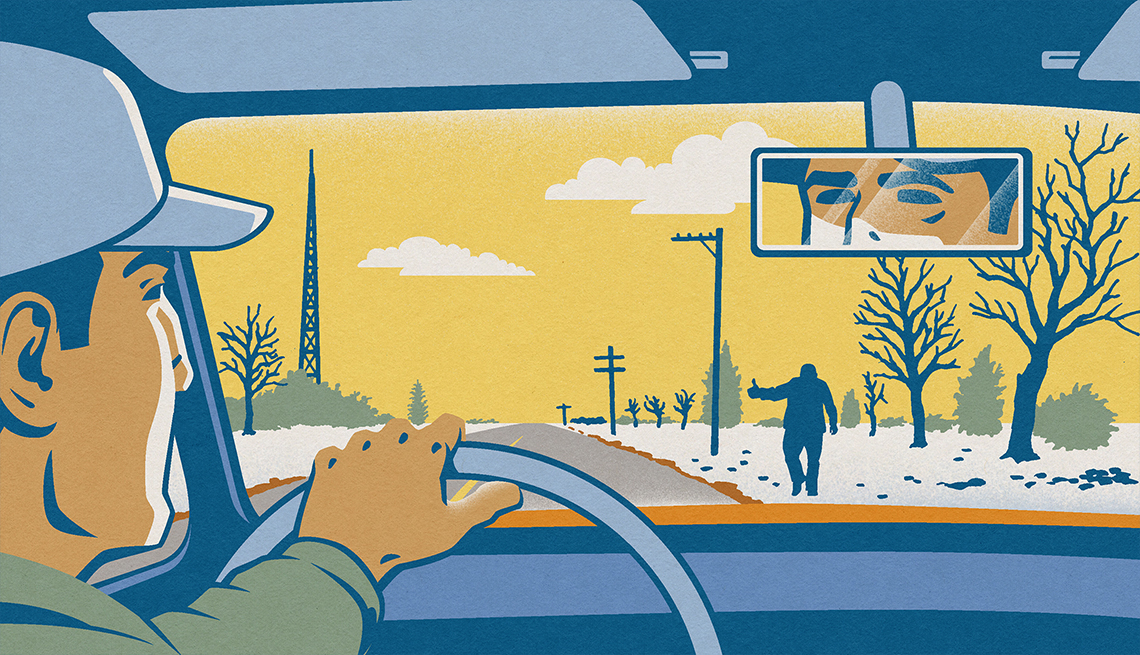

On the way to Traverse City Kermit checked his mobile phone every ten minutes, announcing over and over “no signal here,” and “weak signal here” as he frowned at it. “That’s why I leave mine in my kitchen. Signal’s good there,” I responded, but mostly I wasn’t paying attention. I was brooding over what it could possibly mean that the voice inside my head now claimed to be a murder victim. It sounds, well, crazy, but I realized that somehow I had started to buy into it all—I was actually beginning to think of the voice as a separate person, as Alan Lottner, and could see myself eventually growing comfortable with my conversations with him. There was just something so normal about it—another man’s voice, seeming to be coming from my ears and not from within my brain. That’s really what all human interactions are like, right? Kermit at that moment was yammering away about some way he could make money; it was a separate voice, a separate person, and I wasn’t looking at him. And when you talk on the phone, you can’t see that particular person, either. So none of this felt any different than how life usually goes, even if I knew it wasn’t.But murder? What was next, would he want me to avenge his killer? And who would that turn out to be, the president of the United States or somebody? How long before I complacently went along with this idea, too?

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Traverse City is right on Lake Michigan and has fifteen thousand people in the winter and what seems like two million in the summer, as opposed to land-locked Kalkaska, where I think I know just about everybody by their first name. Kalkaska only really has a crowd control problem during deer hunting season, when the boys from the city arm themselves and wander around wearing camouflage pants, drinking beer.

Kermit was happy for me to drop him off at a drugstore to mess around while I checked into Jimmy Growe’s mystery checks. The silence he left behind when he jumped out made me realize just how much talking he’d been doing—I had a voice both in my head and in my truck.

All of the checks to Jimmy Growe had come from one bank. I walked into the lobby, looking around for the Department of Checks from Nowhere That Bounce.

The person who agreed to help me was a large woman, her bone structure as solid as mine, and I could picture her being a Campfire Girl leader for the three daughters whose framed photographs owned most of the real estate of her desk. She was about my age and wore her auburn hair so that it curled a little off her shoulders. Her dark eyes softened in concern as I spread Jimmy’s six checks—five NSF, one uncashed—across her desk. She told me to call her Maureen.

“Oh my,” Maureen murmured.

I explained my connection to Jimmy and Milton, showing her my business card and Milton’s corporate endorsement of the checks on the back. “What I need to know is who wrote these checks. You can see that the signature is not really legible. It could be Whitmore, or Southmore, or Sophomore. Or Whilnose, or Whilmore.” Those had been my best guesses. None of the names I’d suggested were in the Traverse City phone book, and I doubted anyone on the planet was named Whilnose.

Maureen agreed that the names were hard to read, and even pointed out something I’d missed—the signatures didn’t really appear to be the same from one check to the next. “This one is definitely Wilmore,” she pronounced.

“Wilmore,” I agreed, making a note. She watched me write down the name, frowning.

“Please understand, I am not confirming that as the name on the account,” she warned me, somehow sounding less like Maureen the human and more like Maureen the bank.

“Oh, I understand, it just helps. Most people, when they want to assume a name, pick a variation of their own name.” She looked at me dubiously. “Well, that’s what I read in a mystery novel,” I explained defensively. “So you think these are all pseudonyms?” she asked.

“I don’t know, really. I thought you could give me the name of the owner of the account. Maybe it will turn out to be this Wilmore.”

She bit her lip. “We’ve never had a case of a returned check where the payee didn’t know the remitter.”

“It certainly is interesting,” I agreed brightly, watching the doubt etch shadows into her expression. She wasn’t going to tell me.

“You see, Mr. McCann, it would be against bank policy to give out a name on an account.”

“But these are bounced checks!”

“I’m sorry, even under these circumstances.”

“But you said it has never happened before. Come on, Maureen, you mean you have a policy for something that never happened before?”

“Great idea, get her pissed off,” Alan admired.

A slight flush crept onto her cheeks, but she maintained her composure. “I’m sorry. But the owner of this account …” She paused, frowning. Her head came forward sharply. “These are all different accounts!” she exclaimed.

“They are?”

“Look!” She pointed to the hieroglyphics across the bottom of each check. “You have six checks drawn on six separate accounts.”

I wanted to encourage her curiosity. “How in the world could that possibly happen, I wonder?”

Our eyes met. “Someone must have opened six separate accounts with our bank, receiving a packet of starter checks each time.”

“And not using them at all,” I agreed, finally doing some noticing myself. “See? These are all check number one hundred. That would be the first in the series, right?”

She nodded. “Right.”

I held my breath, watching her mull it over. Then the part of her brain that stood guard over bank policy slammed the door on this line of thinking. “Well,” she murmured, searching for the words to tell me I still wouldn’t be getting any information out of her.

Glancing around the office in my frustration, I noticed her degrees and certificates. “Hey, you went to Michigan State!” I exclaimed.

She blinked at the abrupt change in subject.

“Me too!”

We beamed at each other, and then her expression changed. “You’re Ruddy McCann. The Ruddy McCann?” she gasped.

“That’s me.”

“Oh my!” She half rose in her chair as if to shake my hand again, then sat back down. “I didn’t know you lived here.”

“Right down the road in Kalkaska. Went to high school there and everything.”

“What a small world,” Maureen breathed. “I had no idea.”

We spent a moment looking inward at our college memories. “What happened to you, didn’t you play professional football? I remember everyone saying you were going to win the Heisman Trophy, and then …” Her face turned gray as she remembered what did happen to me. “Oh my.”

I waited. People have various reactions to my past, and I didn’t know what direction Maureen would take.

“I’m so sorry,” she murmured. I could see that she was; her deep brown eyes were sagging under the weight of tragedy.

“It was a mistake I will regret for a lifetime,” I told her sincerely.

“What was?” Alan demanded.

The silence was awkward but I let it build for a moment, then I leaned forward. “Maureen, Jimmy Growe is a very simple guy. I kind of take care of him, like the big brother he never had. He pushes a broom for a living. When these checks arrived, he felt like he had won the Lotto. Now, you and I would probably wonder what the heck was going on, but Jimmy just ran out and cashed these with my employer. And, Jimmy being Jimmy, the only tangible item left from all that money is a motorcycle. Which, knowing Jimmy, he bought from someone who probably took him to the cleaners, so when he sells it he will be thousands of dollars in debt. If I don’t get to the bottom of this, it is going to take Jimmy years to get out of trouble. He still doesn’t really understand what is going on—he offered to pay me by giving me this last, unendorsed check here.”

Maureen made a noise in sympathy. I could see her mothering her image of Jimmy, so I decided to leave out the part about him being the hottest stud in Kalkaska.

“Couldn’t you please look into this? If it is a joke, it has gone way, way too far. These checks are doing Jimmy a lot of harm.”

Her maternal instincts pushed her over to the dark side of banking. “Yes, all right. I’ll be right back.” She swept the checks off her desk and left the room.

“You were a Heisman Trophy winner?” Alan demanded.

“No,” I told him.

“What was she talking about, then?”

“Alan, is it lonely in there? No one to talk to?”

“You don’t know the half of it. When you’re moving it is all I can do to hang on, like when you were driving and that Kermit was talking about how he was going to make all that money by processing credit card charges. But when you’re sitting still and I feel more in control, I want to scream, because—”

“Alan, shut up.”

He bit off his rant in what I swear sounded like hurt silence.

“You are not in control. I am in control. And when I am conducting a conversation with someone, I want you to be quiet. If you are, then when we’re alone, I’ll talk to you. If you’re not, then I’ll never answer you again, and you’ll never have anything approaching a dialogue with anyone unless you leave me and go into somebody else’s head. Okay?”

He didn’t answer.

“Alan?”

“Oh, am I allowed to speak now?”

Maureen was back in the room, carrying a ledger book. “This is very disturbing.” She sat down heavily and stared at me, wrestling with what she had just learned.

“Maureen?” I prompted.

“Well, we still maintain this log in addition to the computer. Whenever we issue starter checks we write down the name and date, here.” She pointed to the list and I looked at it from an upside-down angle. Customer information fl owed across the register in neat rows. I sensed there was a lot more, and waited for her to tell me.

“The thing is, Mr. McCann, none of these packets were ever issued to a customer. See? The account numbers are printed right here. Someone has drawn a line through them.”

“Why would anyone do something like that?”

“Well, sometimes an error is made, and we just void out the account. Under those circumstances, we would mark through the number here and destroy the starter packet.”

“Does that happen a lot?”

“Well, not a lot, but it does happen. Someone should have noticed this, though. Oh.”

“Oh?”

Her eyes were now unreadable as they met mine. “Oh my.”

“What is it, Maureen?”

Wordlessly, she spun the book around for me to see. I glanced down the list of names, noting that the starter packets with the lines through them were grouped together, all issued in December, all within a day or two of each other.

“The handwriting,” Alan murmured.

“The handwriting,” I repeated stupidly.

“Yes. The word void looks like it could be the same as on the checks,” Maureen agreed helplessly.

I looked at her in amazement. “So the bank has been sending Jimmy these checks?”

“No! Oh no, Mr. McCann. Not the bank. An . . . employee.”

“Why would they do that?”

Maureen shook her head, her look as blank as Jimmy’s had been.

“I need to talk to the employees,” I declared grimly.

Maureen appeared shocked. “Oh no, we couldn’t allow that.”

“But ...”

“No, I’m sorry, that won’t be possible.”

I don’t like it when people tell me something I want to do isn’t possible. When I spoke again, it was slowly and deliberately. “Maureen, you need to understand, Milt isn’t trying to go after the bank. We just need to get to the bottom of this. Can you look into it, figure out what happened, who did this? You know. Just compare the log here to people’s handwriting. We’ll keep this quiet. There is no need for Milt to report this to the authorities.”

Maureen’s eyes searched mine. Alan was silent but I swear I could feel his distaste for my subtle threat. Finally she pressed her lips together, nodding unhappily.

“Good, I’ll call you in a day or two to see if you found anything out for me, okay?”

Maureen nodded again, and I shook hands with her and left the office. I was the first to speak in the parking lot. “What, what is it?” I challenged.

“She was helping you and you made it sound like if she didn’t cooperate you’d haul her down to gestapo headquarters,” Alan sniffed.

“Alan, I’m a repo man. I collect money, and if people don’t have any I take away their cars. How do you think I do that, send a Hallmark card with a puppy on it?”

“It was mean.”

I stopped walking and faced a small snowman some children had built so that anyone watching would assume I was arguing with it and not with a voice in my head like some crazy person. “Yeah, well, what do you do for a living?”

“I sell real estate,” he answered loftily.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members