Staying Fit

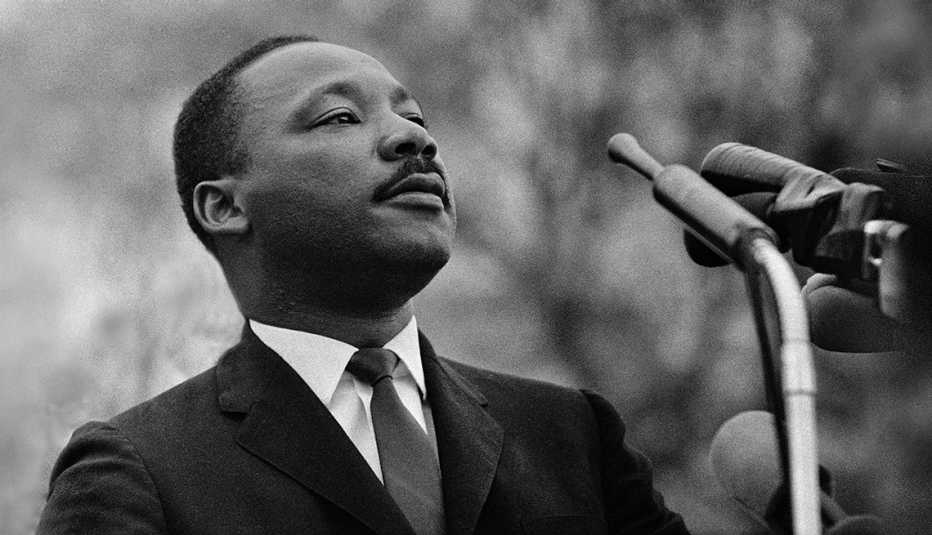

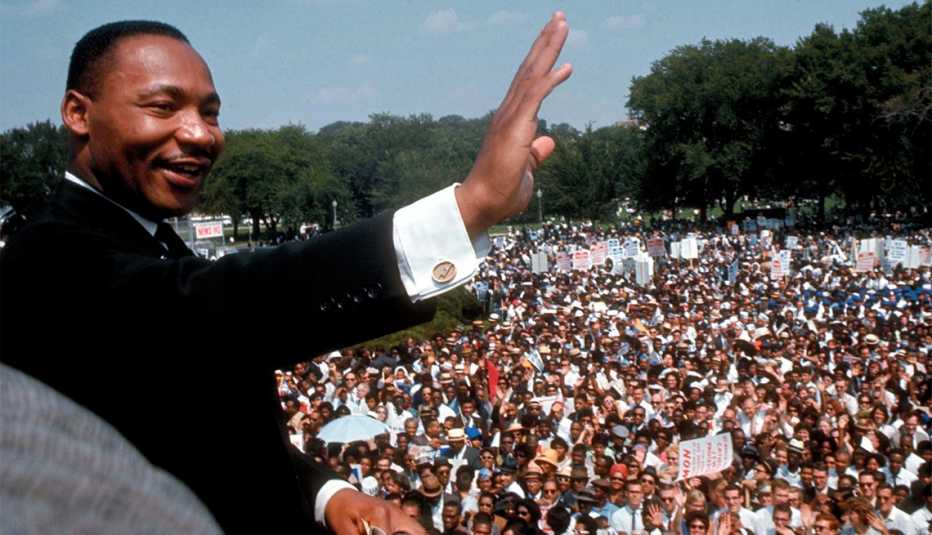

As a young community leader in the 1950s, Martin Luther King Jr. could likely not have imagined how the civil rights movement he helped set into motion would evolve. At 26, his immediate goal was leveraging young Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a local bus into a national movement. But over the next 13 years until his death in 1968, King and a wide range of associates kept their feet on the gas, demanding voting reforms, desegregation and other basic civil rights. Their efforts bore fruit when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were signed into law.

King, who would have turned 94 this year, and his historic efforts continue to inspire others to champion civil rights issues in new arenas and novel ways. Here are few of those people to recognize on Martin Luther King Jr. Day:

Stacey Abrams, 49

Historically, the path to voting for African Americans had been obstructed by literacy tests, poll taxes and intimidation until the original Voting Rights Act cleared the way. But some of those gains have been reversed in recent years. As founder of the Atlanta-based nonprofit advocacy group Fair Fight, former Georgia State Rep. Stacey Abrams has built voter-protection teams, sought to promote fair elections nationwide and helped register more than 800,000 new voters throughout Georgia. Across the country, political candidates like Beto O’Rourke, Pete Buttigieg and Mike Espy have sought her counsel on mobilization efforts. While her own campaigns to become governor of Georgia were unsuccessful, her impact on voting is undeniable.

“Anytime you see [Senators] Ossoff and Warnock and [President] Biden in Washington,” the Rev. Al Sharpton has said, “you’re looking at the work of Stacey Abrams.”

The Rev. William Barber II, 59

William Barber was 4 years old when King visited the Mississippi Delta and saw a teacher divide up an apple to feed eight children. The hunger and misery the leader witnessed inspired the Poor People’s March on Washington: a caravan of more than a dozen covered wagons with slogans such as “Feed the Poor” painted on the side. The procession traveled from Marks, Mississippi, to the nation’s capital for a six-week protest. Barber, who followed in King’s footsteps as a pastor, has continued to carry on similar work across the decades.

“This level of poverty and greed in this, the richest nation in the history of the world, constitutes a moral crisis and a fundamental failure of the policies of greed,” Barber told the crowd, where he was joined by King’s youngest daughter, the Rev. Bernice King, who also spoke at the event.

Bryan Stevenson, 63

At the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, lawyer Bryan Stevenson and his team have won reversals, relief or release for more than 135 wrongly condemned death row prisoners.

Now the organization, led by Stevenson, is expanding its reach through an anti-poverty initiative that works with food banks, anti-hunger organizations and other local partners to provide aid to Alabamans in need. The new initiative will also help people manage fees and fines for misdemeanors and traffic offenses, and create a new project focused on offering free health care.

Through the Equal Justice Initiative, Stevenson has also founded the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice — commonly called the Lynching Memorial. This memorial calls attention to the history of lynching in America.

Stevenson’s work has been showcased in the award-winning documentary True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality and the motion picture Just Mercy, starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx. It is based on Stevenson’s 2014 best-selling memoir of the same name.

Dorceta Taylor, 65

“In King’s day, we fought to drink from the same fountain. Today we fight to drink the same quality water,” says Dorceta Taylor, a professor of environmental justice at Yale University.

She previously served at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, an hour’s drive south of the predominantly African American Flint, Michigan, where residents suffered toxic lead levels in the water. More recently in Jackson, Mississippi, aging infrastructure and severe weather have resulted in a water shortages and unsafe drinking water, a situation exacerbated by the city’s racial inequities.

King often spoke out against pollution, overcrowding and the need for parks — issues that today would be considered a call for environmental justice, Taylor notes. Even the Montgomery bus boycott ties in: It ushered in a year of carpooling, she says.

A senior associate dean of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Yale, Taylor runs two diversity pathway programs to help low-income, students of color, first-generation and allies gain work experience through internships in environmental organizations and agencies.

Lateefah Simon, 45

Early on in her career as the head of San Francisco’s Center for Young Women’s Development (now the Young Women’s Freedom Center), Lateefah Simon’s star rose for her work in aiding formerly incarcerated women, as well as girls who battled drug addiction, prostitution and abuse. Like King, who drew national attention at 26 for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Simon was also a fledgling 26-year-old when she won the prestigious MacArthur “genius” grant.

An enduring racial and civil rights advocate in the Bay Area, today Simon’s string of successes include leading change through grant-making organizations like the Meadow Fund and the Akonadi Foundation; spearheading San Francisco’s first reentry anti-recidivism youth services division; and launching the Second Chance Legal Services Clinic, protecting communities of color, and low-income persons, immigrants and refugees.

During the pandemic, she sourced funding so that employees of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) didn’t lose their jobs. Simon, who is legally blind, is a lifelong rider of public transportation and champions the power of access.

Rashad Robinson, 44

In the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, community activism was more word of mouth. Grassroots folks circulated flyers, worked the phones and placed ads in the paper to get attention. That worked just fine for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, where 40,000 Black bus riders chose other modes of transportation for more than a year.

In the current era, Rashad Robinson, head of the racial justice organization Color of Change, brings innovation to organizing. His nonprofit connects with its 7 million members via social media and online petitions, giving people an accessible way to weigh in on such issues as criminal justice reform, racial discrimination in the federal Paycheck Protection Program or Fortune 500 corporations’ support of white nationalist organizations.

Color of Change’s ongoing Voting While Black website provides an online community hub for civic engagement. Before his current role, Robinson, who’s based in New York City, was senior director of media programs for GLAAD—formerly the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. He continues to explore how racial justice and the LGBTQ movements can work in solidarity.