Staying Fit

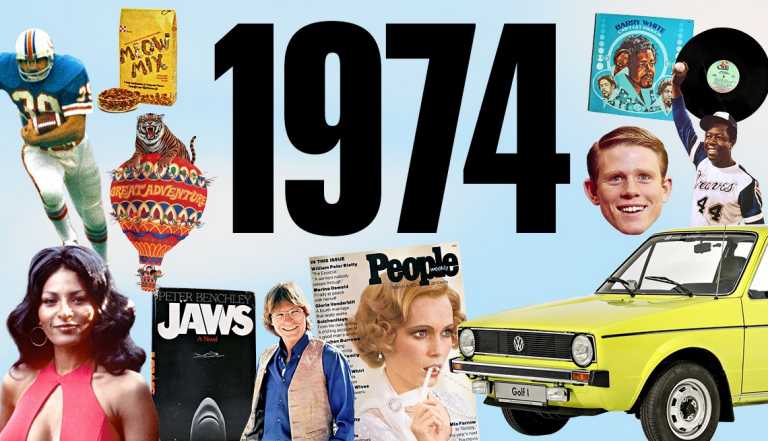

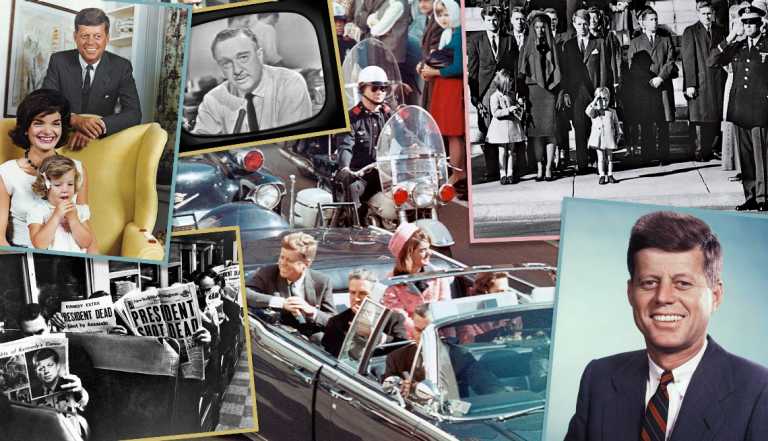

Events & History

Discover new insights into moments that have shaped our history and commemorate milestone events

Explore More Events & History

AARP Membership

$12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Events & History Quizzes

AARP IN YOUR STATE

Find AARP offices in your State and News, Events and Programs affecting retirement, health care and more.