AARP Hearing Center

Jenyce Gush was a teenager skipping school in Dallas. Dean Kahler was a college kid walking on campus to class. Clara Jean Ester was a young woman hoping to meet a hero in Memphis. Each was an ordinary person who lived through an extraordinary event. Read on to learn about people like us who saw a page or even a chapter added to the history of our time.

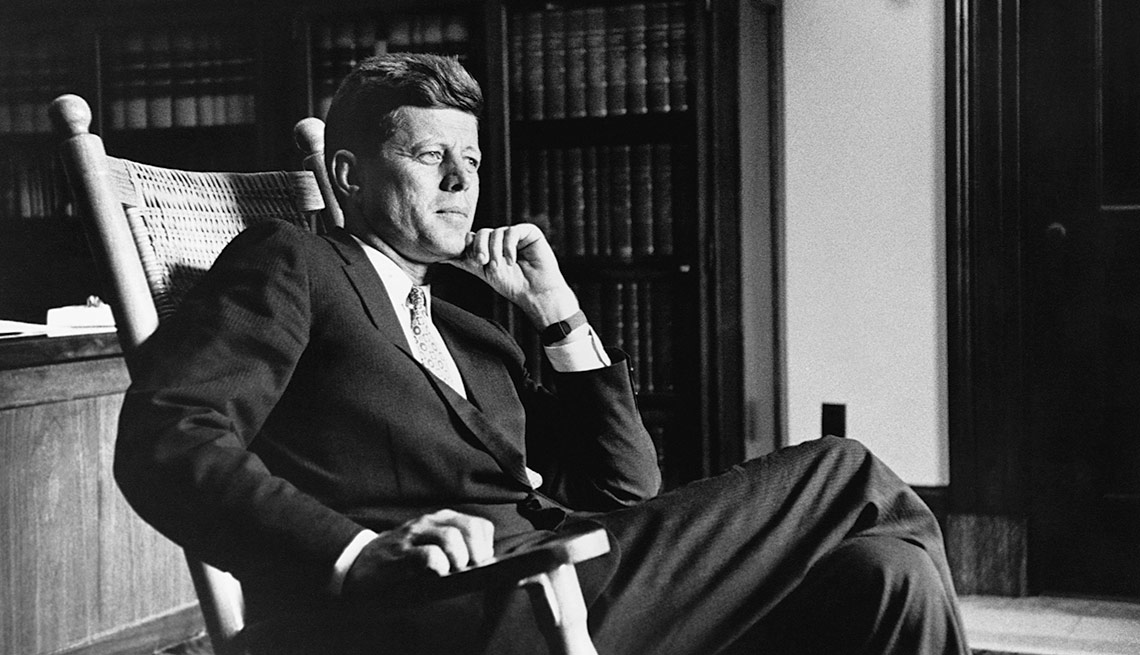

Death of a president

Jenyce Gush, 73, director of volunteer services at the Suicide and Crisis Center in Dallas, on the JFK assassination

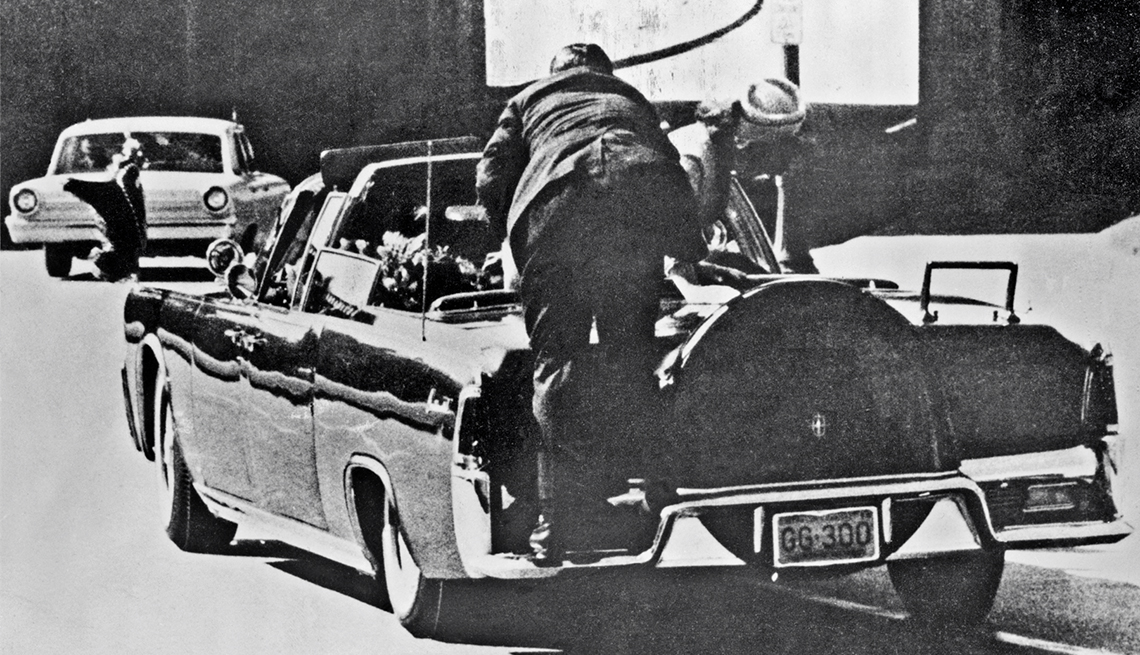

On November 22, 1963, a friend and I decided to skip school. We knew that the president was visiting Dallas and that his motorcade was going to come right down Lemmon Avenue. I was 15 years old, going to Rusk Junior High. The whole city came alive. It was the most exciting thing I’d ever seen. I was standing on the curb on Lemmon Avenue, wearing big pink rollers in my hair, when I saw the governor of Texas, John Connally. And then there they were — the president and the first lady — in an open Lincoln limousine.

I was in awe. This was the Camelot era. There had never been a president like John F. Kennedy or a first lady like Jackie. I was surprised to see them in an open car, that there was no bulletproof bubble. But mostly I was thinking about how attractive he was. He had on a pinstriped shirt, and he had these bushy eyebrows. I looked at Jackie, who was the epitome of beauty, with lipstick that matched her pink suit. I waved at them, and President Kennedy’s eyes fixed on me because I looked funny wearing these big pink rollers in my hair. He waved.

About a half hour after I saw the president, suddenly I saw this lady hysterically screaming in front of what was then Skillern’s Drug Store. She was yelling, “They shot him! They shot him!” I thought she was talking about someone she knew, a family member or something.

“They shot who?” I asked.

“They shot the president!”

“No, no,” I said. “We just saw him.”

I went into Skillern’s Drug Store and saw people huddled around a TV. No one spoke. It was surreal. That is when I heard Walter Cronkite say those haunting words: “From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, 2 o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago.”

I thought, This can’t be happening.

For days, it was all anyone could talk about. It was such a dark time for the whole world. My mother had previously worked as a waitress for Jack Ruby, at the Carousel Club. So when Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested and Jack Ruby was captured on a television camera shooting Oswald, it was just unbelievable. Within a short period of time, the FBI showed up at our door. I answered, and there were these two agents with badges. I panicked, shut the door in their faces and ran to get my mother, who was asleep. “Mother!” I said. “My God! The FBI is here! Did y’all kill the president?” Somehow, my young mind had made that leap. Of course, she had nothing to do with it.

Looking back, it was something you never dreamed could happen, and certainly not in your own hometown.

Ballad of Lady Diana

Mary Robertson, 78, unlikely friend of the princess, on the day of her funeral

In 1980, my husband got transferred to London for his job at Exxon, and before we left, a neighbor gave me the name of an agency she had used when she was in London, to find a babysitter. I was going to work for a bank part-time and needed help with my 6-month-old son, Patrick. We got to London and I rang the agency, which was called Occasional & Permanent Nannies. “Here’s someone,” the woman on the phone said. “Her name is Diana Spencer.”

So, this young woman showed up for an interview. She was 18. The name Diana Spencer meant nothing to me.

She and I hit it off, and I hired her on the spot — didn’t even check her references. For the next year, she came to my house two days a week. We had a very intimate relationship. I called her Diana, and she called me Mrs. Robertson.

One day I found a bank deposit slip sticking out of a sofa in my living room. The slip was from Coutts, the bank for the aristocracy and the royal family. And the name on it was Lady Diana Spencer. I knew that this was an important title. So, I took the deposit slip to the bank where I was working, and there we looked up Lady Diana Spencer in a book on the aristocracy. It just seemed impossible, and one of the British bankers said, “We think you’re great. But there’s no way that someone with her pedigree would be working for an ordinary American like you.”

She had been taking my son to “Kensington” to play with her sister’s little girl. She did not tell me that Kensington meant Kensington Palace, because her sister was married to the queen’s assistant private secretary. When our family moved back to the States, these little blue airmail letters started arriving. She wanted to share what was going on in her life and to tell us how much she missed Patrick and me. Of course I was reading in the newspapers about her relationship with Prince Charles. Then, one day in February 1981, my phone rang. It was a friend from London. She said, “Your girl made it!” I literally jumped for joy. Then came another note. “Of course,” Diana wrote, “you will be receiving an invitation to the wedding.” We went to the wedding and also to this fabulous party at Buckingham Palace two days before. Prince Charles could not have been more gracious. I believed in the fairy tale. I thought this was going to work out wonderfully.

For the rest of Diana’s life, we wrote letters and saw each other when we could. I knew she was having a hard time. The last time I saw her was at a private lunch at Kensington Palace, just her and me and my two children. The food was not kid-friendly, but Diana cut my daughter Caroline’s chicken puff pastry for her. Caroline fell in love. This was a real-life princess.

One night in August of 1997, I was awake at 2 a.m. because we’d had a family party. A friend called. “Mary,” she said, “go turn on your television. Diana has just been killed in a car crash in Paris.” I rushed downstairs, turned on CNN and watched for hours. It all seemed so unbelievable. I’ll never know who thought to invite us to the funeral. Diana was the only person in the royal family that we knew. But I got a call from Lord Chamberlain, inviting me.

Fall of the Berlin Wall

David Patton, 58, of Connecticut College, on the barrier’s crumbling

In September 1989, I got to West Berlin. I was 26 and a Ph.D. student at Cornell University. It was a time of great change. People were trying to leave East Germany. Protests were going on. In October, East Germany’s leader, Erich Ernst Paul Honecker, resigned. It was clear something important was going on, but nobody was talking about the wall coming down. That seemed a long way off, if it was to happen at all. On the afternoon of November 9, I was listening to a press conference. A communist East German official was reading a new policy on how East Germans could leave the country, and he kind of messed it up. From what he was saying, it sounded like the Berlin Wall was going to open up, although that was not his intention. Crowds began to gather in East Berlin. I was in the West, so I couldn’t see these crowds, but I knew the pressure was building. Eventually, some border guards opened gates, and the crowds from East Berlin poured into the West.

The following morning I went down to the wall. I have a picture of myself standing on the wall that day, celebrating. West Berlin was full of East Germans, and they were welcomed. There was a party atmosphere. Many from the East were driving their smoky East German cars — the Trabants. Everyone was delighted, because nobody expected it.

Over the next days, the wall came crumbling down, and I have pieces of it. You could tell who was from the East by their clothing — they didn’t have Western jeans, for example — and by their hairstyles. Little details stand out. I remember the West Berlin newspapers had inserts with free maps in them, because East German maps showed West Berlin as basically uncharted territory, so the newspaper map inserts showed the East Germans where the streets were and how to get around. Many East Germans saw food items they had never seen before; bananas were talked about at the time, because you wouldn’t have been able to get bananas in East Germany.

I stayed in Germany for nearly another two years. I ended up moving to a cheap, dilapidated apartment in what was formerly East Berlin, and I was in Germany on October 3, 1990, when the country reunified. I was there researching German foreign policy, and I was able to include my experiences in my dissertation and later in a book. What I remember, most importantly, I think, is how unexpected the fall of the wall was, how quickly it happened and the lesson we can learn. Circumstances that you can take for granted can change so quickly. Just because things are the way they are today does not mean they will be like that tomorrow.

Birth of the Mustang

Gail Wise, 80, a former schoolteacher, on a car story like no other

On April 15, 1964, I went with my parents to Johnson Ford, a car dealership on Cicero Avenue in Chicago, to buy a new car. I was 22 years old and had just graduated from Chicago Teachers College. I’d gotten a job in the suburbs, but I still lived at home, so I needed a car to get there.

“I want a convertible,” I told the salesman. “Come in the back room with me,” he said. “I have something special to show you.”

We went into the back room, and there was this car, under a tarp. He pulled off the cover, revealing this marvelous skylight blue automobile. It looked sporty and small, and it had bucket seats. I loved it right away. The salesman explained that he wasn’t supposed to show anyone this car, that it was going to debut two days later. But he let me buy it. It was a convertible and had all the bells and whistles, and I paid $3,447.50. My parents loaned me the money. Many years would pass — decades, in fact — before I would learn that I was the first person in the U.S. ever to buy a Ford Mustang. That day, when I drove out of the dealership, people were waving and asking me to slow down so they could see the car. Even police officers. The day after that, when I drove to my job, the seventh- and eighth-grade boys gathered around the car. They were so excited! I felt like a movie star. I wrote a letter to my boyfriend, Tom, now my husband of 56 years, about the car. He was in the Navy, out at sea, and when he wrote back to me, he told me he had never heard of a Ford Mustang.

On April 17, two days after I’d bought my car, Ford Motor Company debuted the Mustang at the New York World’s Fair, in a ceremony with Lee Iacocca, who became known as the Father of the Mustang. Suddenly there were Mustangs everywhere. The car became so popular that Ford could not make them fast enough.

My husband and I drove that car for 15 years. Then one day he came home from work and said, “There’s something wrong with the car.” He put it in the garage and said he would fix it “next week.” That next week turned into 27 years. Tom saw a guy online claiming to be the first Mustang owner. He said he had bought his Mustang on April 14, 1964, in Canada. But I had bought mine on April 15, and I had all the paperwork. Eventually, Ford verified that my Mustang was the first one sold in the U.S.

More From AARP

10 Events That Shaped Hispanic America in 1973

A snapshot from 50 years ago highlights political, art and entertainment moments in the lives of U.S. LatinosBernice King, MLK’s Daughter, Reflects on Legacy

On the 60th anniversary of the historic 1963 March on Washington, King ponders its impact

Unique First Ladies Through History

A look back at some of the women who’ve called the White House home