Staying Fit

Ninety years ago, Wall Street laid an egg.

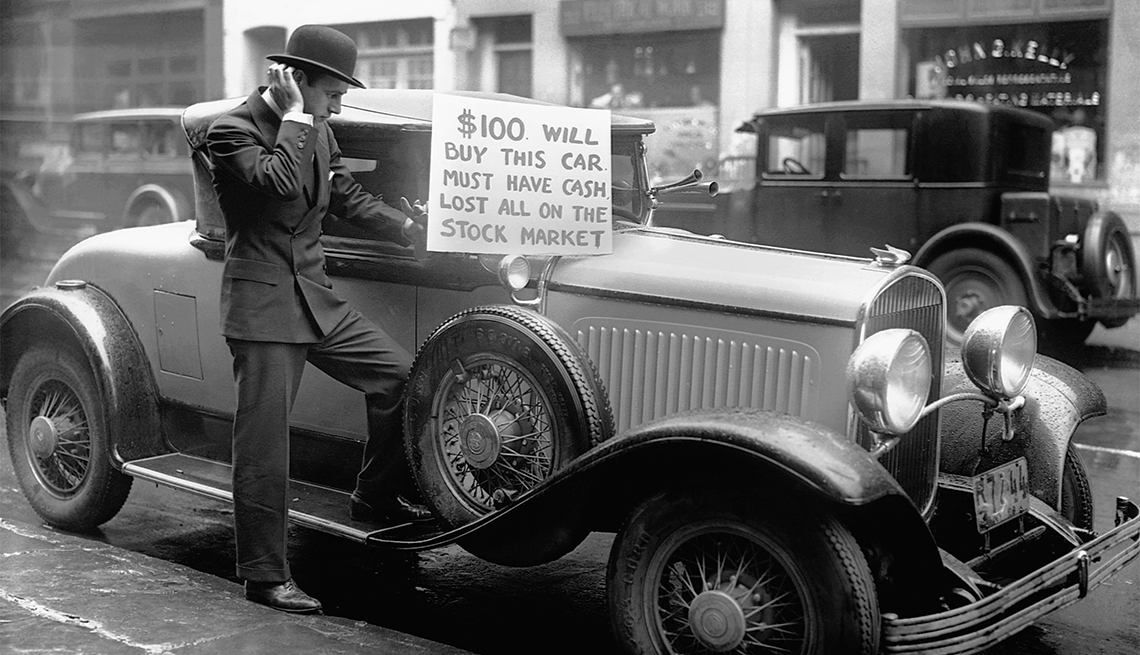

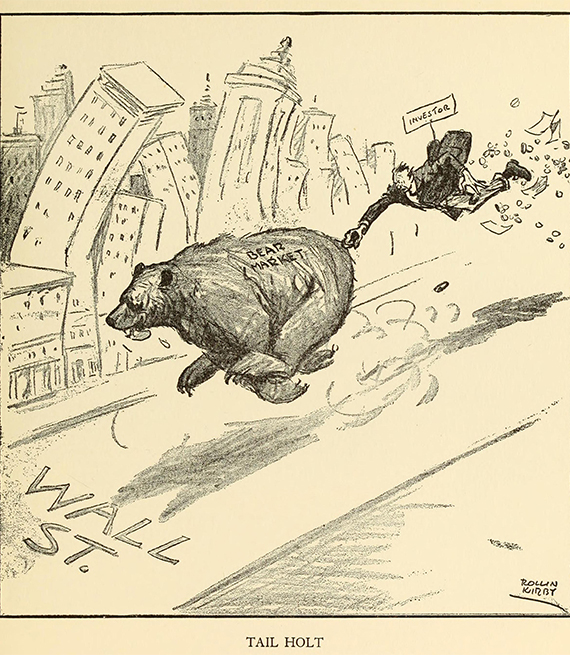

On Oct. 24, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average began a slide that saw a 12.8 percent plunge Oct. 28 and a 11.7 percent decline the next day.

By the end of the bear market in 1932, the Dow had plummeted 89 percent from its 1929 high, erasing all the gains of the Roaring Twenties, and the nation was in the depths of the Great Depression.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Historians have found plenty of reasons for the Great Crash, ranging from excessive speculation to a slowing global economy to shady investment practices. Even though the world is very different than it was in 1929, we can learn plenty of lessons from the Great Crash and the economic disaster that followed.

4 always-good pieces of advice

1. Diversify. Even though stocks cratered in the 1929 crash, government bonds were safe havens for investors. A position in bonds probably wouldn't have shielded you completely from stock-market losses, but it certainly would have softened the blow.

2. Keep cash in reserve. Your most important investment is you, and if you lose your job, you'll need some savings to enable you and your family to stay afloat.

In addition, a cash stash can help you pick up bargains in the aftermath of a market decline. During the Depression, mutual fund pioneer John Templeton invested $10,000 and bought shares of 104 companies for less than $1 a piece. He sold them for around $40,000 near the end of World War II.

3. Never bet more than you can lose. Buying stocks on margin, often with as little as 10 percent down, was common in the runup to the crash.

If your stock rose 10 percent, you would double your money. If it fell 10 percent, you would lose your entire investment.

Some mutual funds put their entire portfolios on margin — and in turn, other funds bought those on margin.

4. Try not to get caught up in hysteria. Stocks had had a long runup to the 1929 crash, and their prices, relative to earnings, were extremely high.

High-tech stocks of the day, such as Radio Corporation of America, were particularly pricey. Soaring prices tempted more and more people to climb into the market, even those who should have known better.

"Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau,” Yale economist Irving Fisher said in September 1929.