Staying Fit

Money

Get the latest financial news and expert advice on money management to budget effectively, spend wisely, build a nest egg and live well in retirement

Explore Money Topics

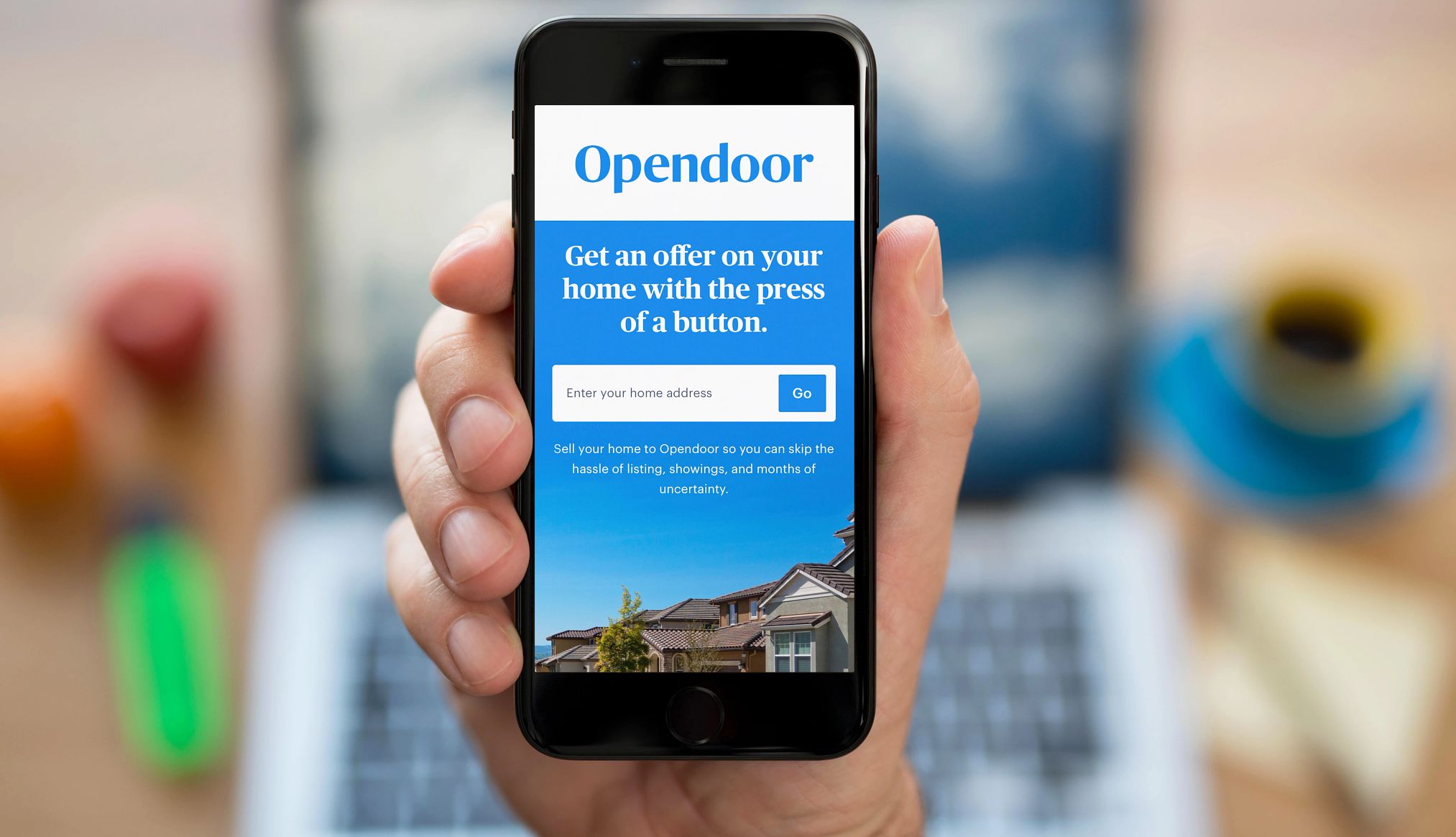

AARP Tools to Manage Your Personal Finances

AARP Membership

$12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Trending in Money

Recommended for You

AARP IN YOUR STATE

Find AARP offices in your State and News, Events and Programs affecting retirement, health care and more.