AARP Hearing Center

At age 18, my father, Pincus Mansfield, volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, but he was rejected. He had only one good hand. But he returned and convinced the Air Force that it couldn’t fly without him. He was inducted on Aug. 13, 1943, and was trained to be a waist gunner, one of the men shooting a machine gun out of the open “gun port” of the B-24 Liberator bomber.

“My parents thought I was nuts and did until their dying day,” he said. His Uncle Sammy bought him a trumpet at a hock shop. “Here, when they hear you play maybe they won’t send you overseas,” Sammy said. He didn’t think his one-handed nephew was going to win the war.

Why would they take a one-handed 18 year old? The short answer is that in 1943 they were losing 75 percent of the men they trained and sent into battle. The Eighth Air Force had more deaths — 26,000 — than the entire Marine Corps. Only Pacific submarine crews suffered a higher fatality rate.

On my father’s 19th mission, over Kassel, Germany, he was hit by flak. He was shot up pretty badly, hit in the legs, buttocks and face. He was sent back to the United States and was hospitalized for 164 days.

You can subscribe here to AARP Experience Counts, a free e-newsletter published twice a month. If you have feedback or a story idea then please contact us here.

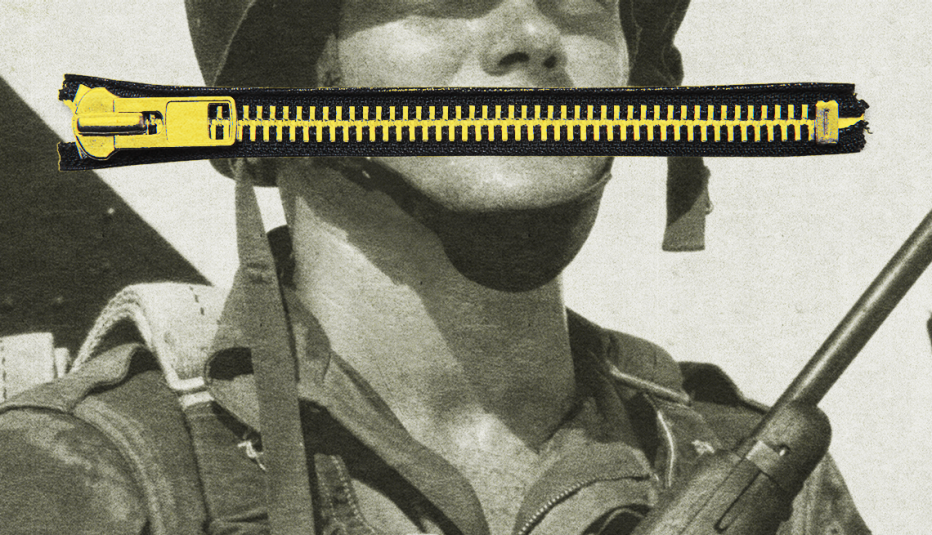

All this was hidden history in our family. My father never talked about the war and we learned not to ask. “I’m not gonna tell any war stories,” he’d say. In choosing silence he was like most men of his generation. It was a rule with him and millions of other veterans. But why?

Shortly before my father died five years ago, I stumbled over the answer to that question. As we were cleaning out the old home, I found a small, folded set of pages that had sat in a drawer for 65 years. It was a short journal of the bombing missions he had flown. I had no idea he’d kept this record. Airmen were forbidden to keep diaries.

I quickly read through it. Some of the missions he flew were harrowing, marked by attacking fighter planes, big anti-aircraft cannons firing from the ground, blowing holes in his bomber and wounding crewmen. They had limped back to England flying on three of the four engines with another engine threatening to quit.

More From AARP

Graphic Novels That Keep Military History Alive

Discover the fresh ways of telling stories of service and sacrifice

Brothers' Vietnam Service Inspires Group for Wounded Veterans

Operation Second Chance has helped thousands of military families

Gary Sinise Salutes America’s Medal of Honor Recipients

These humble heroes wear the medal not for themselves, but for those who did not make it home

Recommended for You