Staying Fit

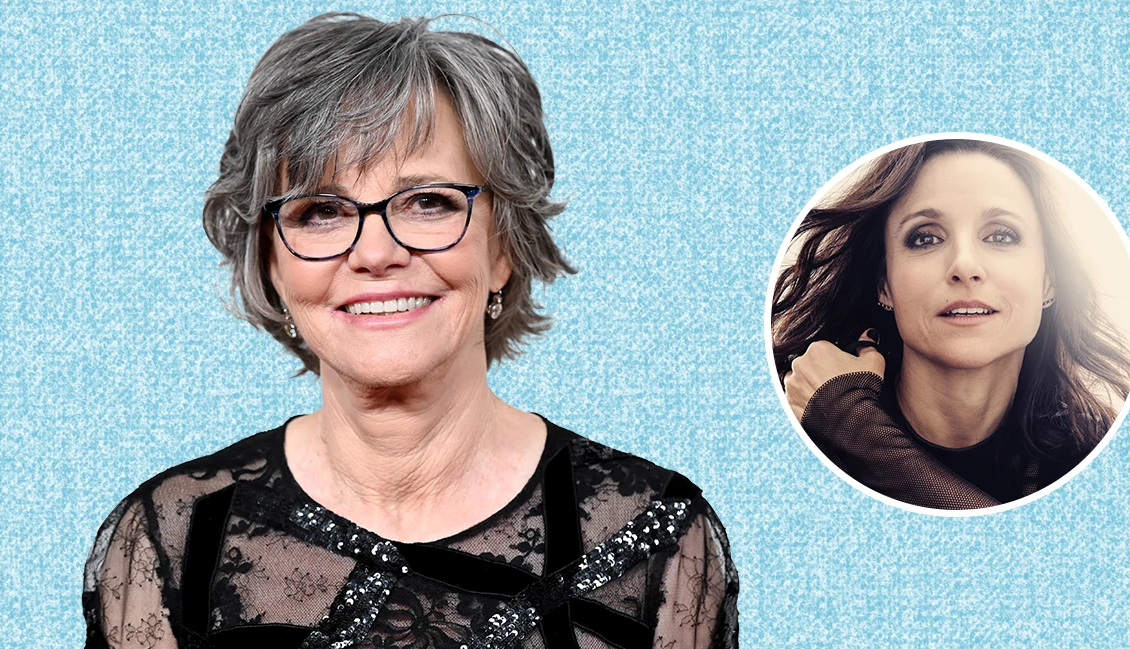

The Movies for Grownups Awards with AARP the Magazine celebrate and encourage filmmaking with unique appeal to movie lovers with a grownup state of mind — and recognize the inspiring artists who make them. Each year the centerpiece honor is the Career Achievement Award, celebrating the contributions of cinema legends.