You were credited with softening his sharp edges.

There was a bit of dusting to do, a bit of clearance. I was, like: “Look, if we’re going to have a family, we’re going to have a relationship.” He had a bit of a cloud over his head. He had a furrowed brow we used to call “the mark of the beast.” Getting completely outside of the music business was refreshing for him. It allowed him to do normal things, go to normal places. And having a child shifts your life’s view.

“Her or Me” is a sensual poem about George’s love for his guitar. Did you feel overshadowed by his massive devotion to music?

“It’s not a competition,” George would always say. I have so much respect for artists and the creative process. That gift is all-consuming and holds a place that floats above. You know it’s coming from somewhere they don’t even know. I experienced that myself when I was writing this book. If we were on holiday and George started to write a song, I would immediately hand him a pencil or paper. I was never jealous of it. I was in awe of it.

You pack a lot into “My Arrival,” a dense chronicle about your difficult adaptation to George’s lifestyle and social circle.

People probably thought I wouldn’t be there that long. You can understand that. I didn’t have any history with anyone, so I had no grudges. I write about coming into his house and putting flowers on his mantel and people saying, “No, no, no. He doesn’t like flowers there.” Being an outsider, it was fascinating.

The poem “She” examines your modest upbringing and its parallels to George’s.

We came from similar beginnings. “She” is about me growing up in Hawthorne, south of Los Angeles. It was a sundown town, which I didn’t know until recently. We were this big Mexican family in a white neighborhood. George was born at home during the war in a two-up, two-down: two rooms up, two rooms down. I once said to one of his peers, “You guys were so skinny.” And he said, “We didn’t have any meat or protein. We didn’t have enough to eat.” Rationing in England took place until 1953. George’s father, after driving a bus all day, took people downtown to air raid shelters.

The companion poem “He (Never Hurt No One)” is a sweet biography.

George was a kind, forgiving, compassionate, nonviolent man, in every sense. He defended his family and was bold to the point of danger when threatened. George was loved and admired. He took criticism, blame and violence he did not deserve, and in all his life, he never hurt no one. He often wrote grammatically incorrect things, and I would try to correct him: “You can’t say that.” “Yes I can,” he’d say. So yes, he never hurt no one.

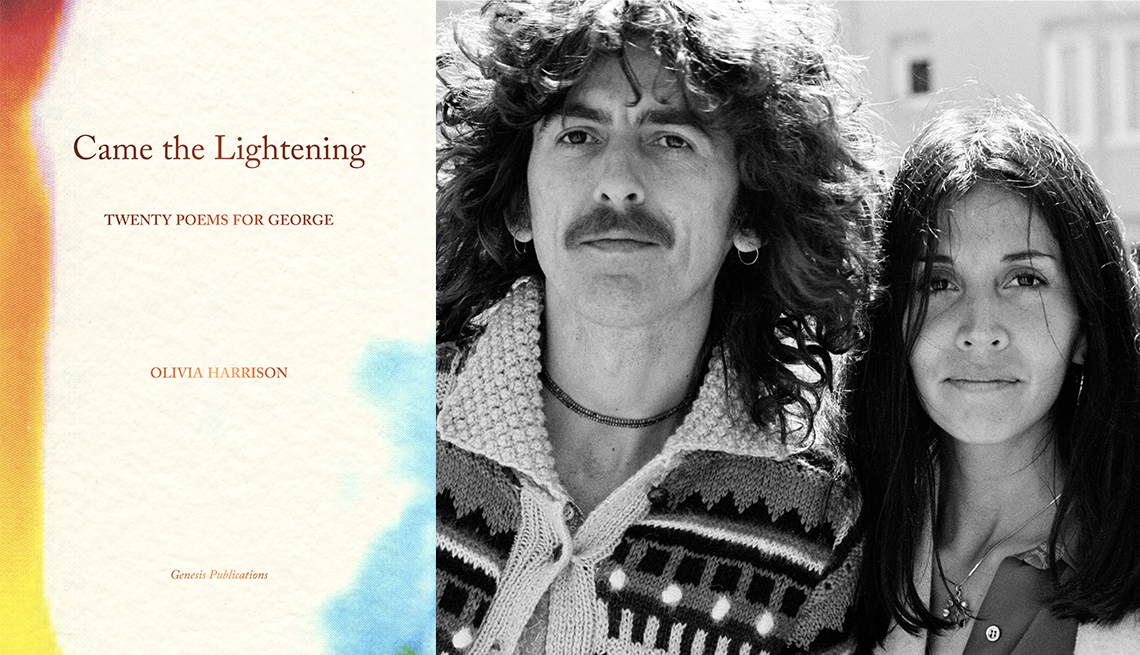

You met while working together. At what point did you know you were meant for each other?

A couple months. I kept trying to go to work! There were 10 people at the office waiting. I think he needed a friend. It developed like that. He was a bit untethered when I met him.

Olivia and George Harrison on vacation together in Italy.

AP Photo/pa/File

Is death the absolute end, or do you think it’s possible you will see George again?

I don’t know. I don’t think there is an end. I think our elements disintegrate. Our fire is going out, our air is going out, but the energy doesn’t end. It just changes form.

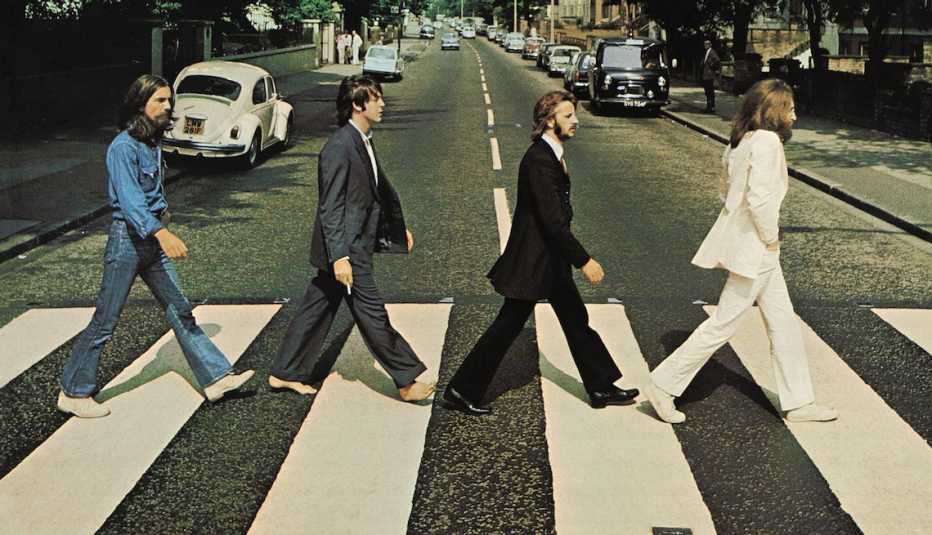

You’ve taken on huge responsibilities as a philanthropist and with the legacies of George and the Beatles. Why haven’t you slowed down?

Maybe there’s a need to feel like you’re going to finish everything before you kick the bucket. How do I balance it? Not very well. I find it hard to focus on things because I want to be in the garden. But writing this book was a real revelation. I really could not stop. I wanted to express that grief. It’s not that I blocked it for 20 years. I certainly went through it and faced it soberly for a couple of years after George died. I thought, What does it mean for me? Same with Dhani. George died for a reason. What is the lesson for us? We better find out, or it’s just a big waste. First Eric [Clapton] called me to do Concert for George. Then we did a movie, we did a book, and then the music. Then some of George’s unreleased music. I have an overdeveloped sense of duty. There are still all these 24-track tapes sitting in the vault.

What potentially could be released?

In 1974, during the “Dark Horse” tour rehearsals, they taped nine concerts in the evenings at Occidental College. And these are with the finest exponents of Indian classical music. Shivkumar Sharma just passed away. They’ve never been released. So I think no one else is going to do it. I better do it. Or the tapes will just rot.

Edna Gundersen, a regular AARP music critic, was the longtime pop critic for USA Today.