AARP Hearing Center

I recently reached what Plato called the threshold of old age. I’m 61 — not old, yet no longer young. The adolescent of senescence. It is an uncomfortable state. I began to cast about for role models. I did not find any. We have plenty of exemplars for pretending not to age, but precious few for actually, well, aging.

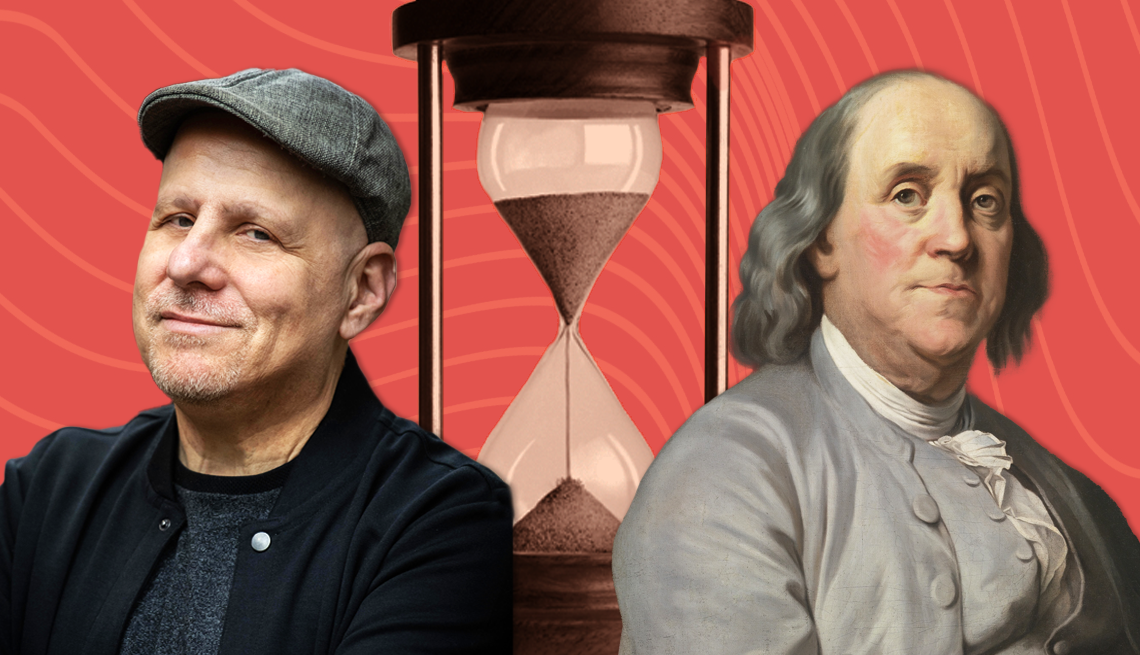

Then I stumbled across Benjamin Franklin and ended up writing a book about him, Ben & Me: In Search of a Founder’s Formula for a Long and Useful Life. He is the model for aging well that I was looking for. The last third of his long life (he lived to be 84) was by far the most interesting, and the first two-thirds were downright fascinating. It was during his closing act that he accomplished the most and changed the most. It was when he became an American rebel, when he charmed the French into supporting the American cause, which helped win the Revolutionary War, and when he signed the Declaration of Independence and Constitution. It was also when Franklin was at his happiest and most fulfilled. The man aged well.

Franklin loved systems, and though he never created one explicitly for aging well, I think he would approve of this list, an homage to this remarkable man on July Fourth, culled from his words and his life.

1. Be grateful for the health you have.

Franklin suffered from his share of health problems: gout and kidney stones, to name just two. He did take steps to alleviate his maladies. He consulted with physician friends and invented medical devices such as bifocals and the flexible catheter. Yet he rarely whined or complained. He treated his body with kindness and gratitude. As he wrote in 1790, some three weeks before his death, “I do not repine at my malady, though a severe one, when I consider … how many more horrible evils the human body is subject to; and what a long life of health I have been blessed with, free from them all.”

In Franklin's eyes, old age was not a failure. It was the natural outcome of a life lived fully. “People that will live a long life and drink to the bottom of the cup [must] expect to meet with some of the dregs,” he said.

You Might Also Like

Read ‘The Excitements’ by CJ Wray Free Online

Lose yourself in this feel-good romp following the law-breaking escapades of two quirky 90-something sisters and WWII vets

‘The Raging Storm’

AARP members can read or listen to the third crime novel in Ann Cleeves' Two Rivers series free online

Read James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’ Free Online

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

Recommended for You