Staying Fit

When we lose someone dear, it’s normal to feel twinges and waves of grief, even years after the death, says psychologist Robert Neimeyer. “That in itself is simply a response to the informed heart,” says the director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition.

But what Neimeyer and other mental health experts now call prolonged grief disorder (PGD) is something different.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

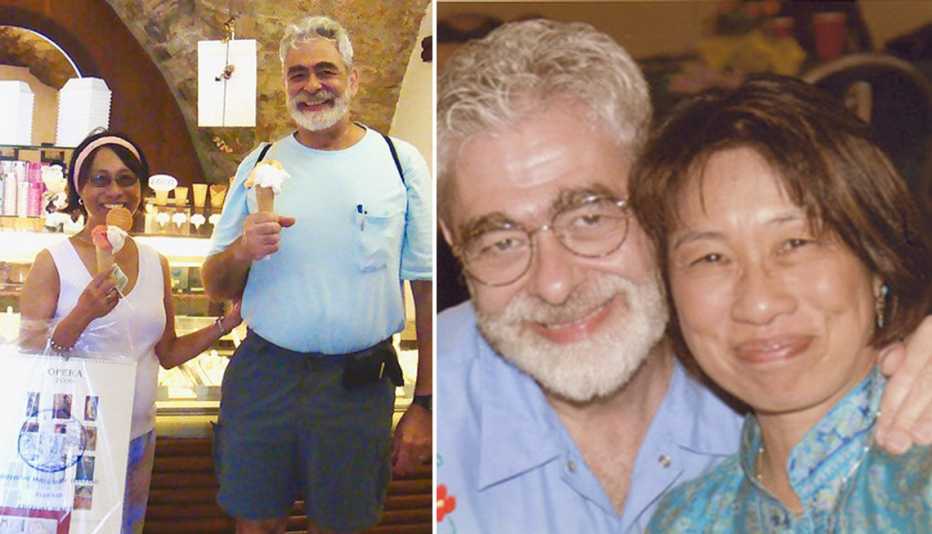

It’s the kind of distress John Barba, 76, of Oakton, Virginia, still felt six years after the death of his wife, Margie, from cancer. One day, he says, he was at home listening to a favorite opera when he was overcome with an out-of-body experience “that Margie was dying, that she was still here, she was dying upstairs in the bedroom.”

Barba, a school psychologist, says that event helped him realize he had never “faced the horror of her death.” He’d had therapy on and off, he says, but still felt “locked in,” and detached from life. He couldn’t work full time, enjoy old friends or savor time with his children and grandchildren. He couldn’t look at pictures of his wife or talk about her. At his younger son’s wedding, he felt no joy, just intense anger that his wife wasn’t there.

In 2017, Barba got specialized therapy for what was then called complicated grief. He’s doing much better today.

Experts hope many more people will get similar help as the result of some recent changes. After years of debate over whether grief could ever be a mental illness, PGD was added to psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2022. (The DSM is the health care handbook for the diagnosis of mental health disorders.) That means more mental health professionals are learning to recognize it and provide targeted therapies, including the type Barba underwent at Columbia University’s Center for Prolonged Grief in New York.

More From AARP

Grappling With Grief When a Grandchild Dies

Sometimes grandparents are the “forgotten mourners”When a Dying Friend Keeps Her Distance

Death doula explains how to respect and accept different end-of-life choices

My Journey as a Family Caregiver in the Wake of Grief

Five months after my mother’s death, I’m feeling more at peace