Staying Fit

Just two hours per week is all the time that family caregiver Ayda Beltré devotes to herself.

That’s on Sundays when she goes to church and must leave her 86-year-old dad, Eugenio, alone. Eugenio is bedridden with a few ailments and has been on oxygen since COVID-19 hit the family in February. Beltré can’t afford the high costs of weekend caregiving help. So, when she leaves the house to go to church to pray for her father’s recovery, it’s a roll of the dice that breaks her heart every time.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

“I give him a big breakfast before I go,” says the 61-year-old resident of Fort Myers, Florida, who is currently unemployed. “While I’m gone, I’m worrying about him.”

High cost of ‘free’ care

For the past six years — seven days a week — Ayda has been a devoted family caregiver for her father because she can’t afford to pay for outside help. During the week, her dad gets 17 hours of caregiving assistance through Medicaid but even then, Beltré says, she rarely leaves the house because she doesn’t feel fully confident in the assistance that the caregivers offer.

Money can’t buy the kind of care that family caregivers devote to their loved ones, from driving to appointments to managing medical claims to providing hands-on assistance. But if it could, the amount is staggering, according to the latest report in AARP’s “Valuing the Invaluable” series.

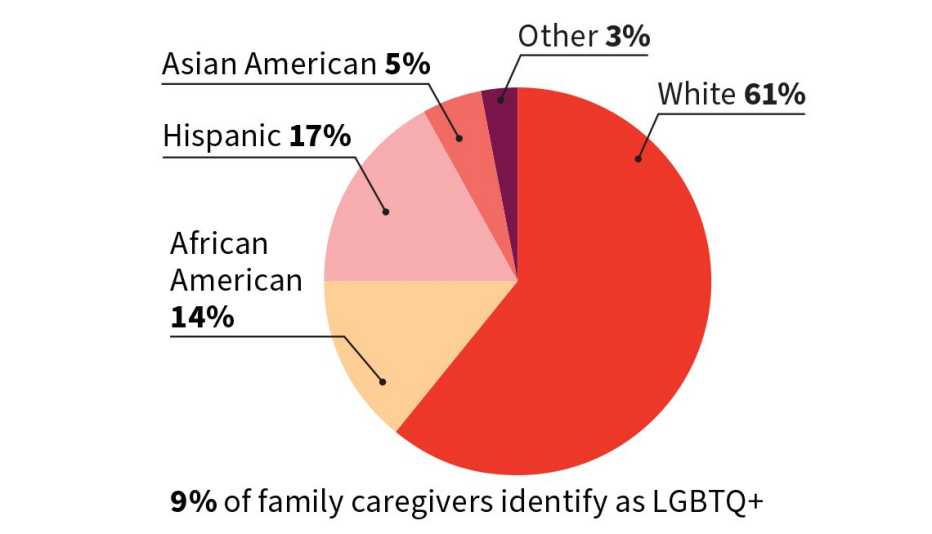

Care provided by millions of unpaid family caregivers across the U.S. was valued at $600 billion in 2021, the new report estimates, a $130 billion increase in unpaid contributions from the 2019 report. The staggering figure is based on about 38 million caregivers providing an average of 18 hours of care per week for a total of 36 billion hours of care, at an average value of $16.59 per hour.

For perspective, that amount is considerably more than the $433 billion spent by families nationwide in 2021 for all out-of-pocket U.S. health care costs. Put another way, the sheer act of trying to save $600 billion by setting aside $100,000 per year would take a total of 6 million years.

Time is money. No one knows this better than the nation’s 38 million family caregivers who devote 36 billion hours of free care to older parents, spouses, partners and friends with chronic, disabling and serious health conditions. Family caregivers are the backbone of the long-term care system in the U.S. But with over 60 percent of family caregivers working either full-time or part-time — and 30 percent living with a child or grandchild — they need and deserve more assistance from city, state and federal governments, says the report. For instance, states can expand caregiving tax credits and workplaces can adapt more family-friendly policies such as paid family leave.

AARP is advocating to turn the National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers, which was delivered to Congress last year, into action that provides tangible help for family caregivers.

“Family caregivers are a scarce resource and should be protected and supported,” says Susan Reinhard, the AARP senior vice president who directs its Public Policy Institute. “If they walked off the job, we’d be $600 billion short.”

The pandemic has impacted family caregivers like nothing else and brought to light the tension that many sandwiched caregivers experience while trying to tend to the needs of their own children even as the needs of their aging parents have increased.