AARP Hearing Center

For nearly two decades, Daniel and Ellen Potts of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, have answered the call of caregiving again and again. Between them, they have provided hands-on care and emotional support for nine family members and close friends — including, today, a beloved friend from their church community who is in the moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Their journey began as kids when both of them had grandparents with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. As adults, their first intimate experience was with Daniel’s father, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2001. At the time, Daniel was a private-practice neurologist, well versed in the clinical side of neurodegenerative diseases. But the personal impact hit him harder than he anticipated.

“Even though I worked with families affected by serious neurologic diseases, it really hit home when it was my turn to be a caregiver,” recalls Daniel, who is now with the Tuscaloosa VA Medical Center. “It shocked me how much I had to learn.”

For Daniel and Ellen, that six-year period until his father’s passing in 2007 was nothing short of transformative. As an only child, Daniel helped his mom care for his father, with help and support from Ellen. “It was a crash course in caregiving,” Ellen adds. “What we knew then and what we know now are extremely different.”

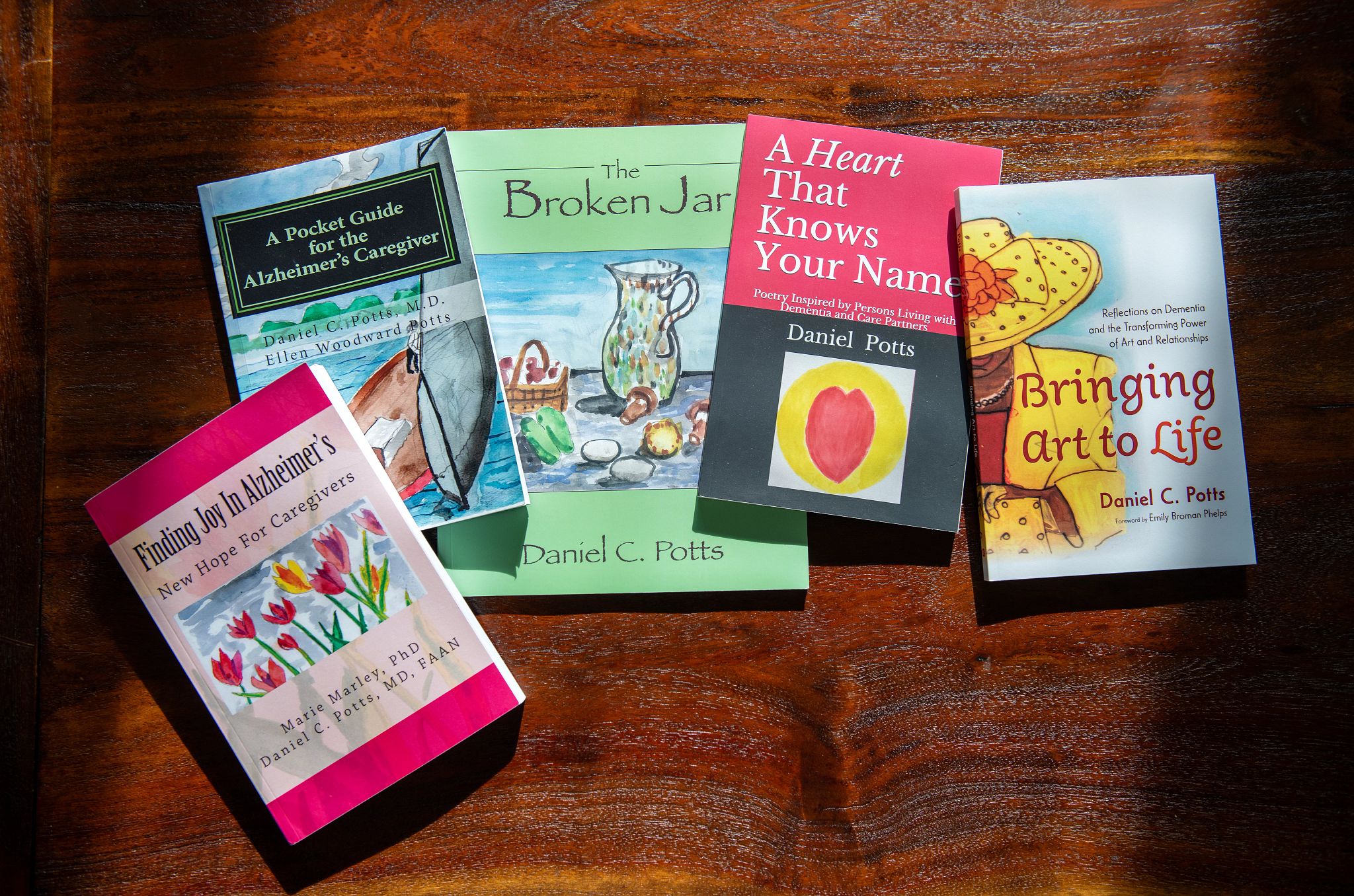

After caring for Daniel’s father, Ellen had a spark of inspiration: Why not write a practical guide for other caregivers searching for straightforward answers? Daniel loved the idea, and together, they coauthored The Pocket Guide for the Alzheimer’s Caregiver, published in 2011.

Since then, Daniel has written two more books on caregiving, including a deeply personal work about an expressive arts program that inspired his father’s watercolor paintings created during his final years, Bringing Art to Life: Reflections on Dementia and the Transforming Power of Art and Relationships.

Lessons in caregiving

Psychologist Julia Mayer entered her second caregiving role after the death of her father from vascular dementia, helping care for her in-laws. Armed with hard-won insight from her experience, one of the most valuable shifts was in how she managed her own expectations. Early in her caregiving journey, she hoped to meet every need, solve every challenge and ensure her loved one’s safety at all times. But over time, she realized that such perfection was not only unattainable; it was unsustainable.

Join Our Fight for Caregivers

Sign up to become part of AARP’s online advocacy network and help family caregivers get the support they need.

While caring for the parents of her husband, psychologist Barry Jacobs, an AARP columnist and contributor, Mayer learned to expect resistance rather than be surprised or discouraged by it. Whether managing medications or preparing meals, she approached each task with the understanding that things might not go as planned. This shift in mindset helped her stay calm, adaptable and focused. Instead of trying to control every outcome, Mayer prioritized her in-laws’ quality of life and embraced the reality of doing her best amid emotionally complex circumstances. Mayer and Jacobs have collaborated again on a new book, The AARP Caregiver Answer Book, a collection of questions that others have asked them about caregiving.

“The second time around, I stopped trying to be perfect and started focusing on what actually mattered,” says Mayer. “My expectations were much more realistic, and I anticipated resistance to doing things instead of being blindsided by it.” Simple shifts made a difference: "”By putting the food on a plate in front of them, they ate much better than when I gave them choices.”

Caregiving experts agree that adopting new mindsets and practical strategies can help make future caregiving experiences not only more manageable but also more meaningful. Here are essential approaches to consider.

Get educated

After his father’s passing, Daniel Potts dove deeply into caregiving research, immersing himself in literature and joining numerous caregiver organizations and advocacy groups. Together with his wife, he found guidance in Joanne Koenig Coste’s book, Learning to Speak Alzheimer’s, which reshaped their understanding of connecting with those living with dementia.

More From AARP

Enjoy These Perfect Puree Recipes

They are easy, creamy and seriously delicious

How to Cope With Guilt After a Loved One Enters a Nursing Home

Look at the big picture to help understand and ease conflicted emotions

Becoming a 'Sudden' Caregiver of a Loved One

Whether due to accident or illness, navigating this unfamiliar world can be daunting