Staying Fit

Chapter One

JEN HAD DRUNK TOO MUCH. They were in Cynthia Prior’s garden, lounging on the grass, and it was just getting dark. The party had moved outside, become quieter and less frenetic. Jen could smell cut grass and honeysuckle, the scent intense, heady and oversweet. She found herself mesmerized by the rhythm of the flashing fairy lights that Cynthia had strung along the high brick wall and woven between the ivy and climbing roses.

Cynthia’s place was the kind of gaff to have a wall around it: a large detached house looking out over Rock Park, only a few hundred yards from Jen’s narrow terraced home, but a million miles in terms of class. Jen was a Liverpudlian and carried the idea of class with her like a badge of honour. Her dad had been a docker and her mother still stacked shelves in a supermarket.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Although it was dark, the air remained hot and the fire in the pit was there for effect, and to toast marshmallows, not because it was needed. They’d had an early heatwave. It was only the end of June but already there were calls for water rationing, talk of standpipes if the weather didn’t break soon. In North Devon, they weren’t usually short of rain.

Earlier, inside the house, there’d been loud music and, despite the warmth, dancing; Jen loved a good dance and could move like a demon. Her husband had disapproved, but she no longer had to care what he thought. Now they’d all drifted outside and Wes, one of Cynthia’s arty mates, was playing guitar, something moody and slow. Nobody could do moody like Wes. Jen had fancied him like crazy when she’d first met him, but then she fancied most of the single men she bumped into. She was a tad desperate. Wes was brooding, dark-haired and fit, the stuff of Jen’s dreams. Later she’d decided that a weed-smoking musician, who lived with a bunch of hippies in the hills, and supplemented his income by making weird furniture from driftwood, wasn’t the best fit for a woman with sole responsibility for two teenage kids. Who was also a cop.

Next to the wall a table had been set up and covered with a cloth. The cloth was Cynthia all over, and showed how classy she was. With the general exodus, Cynthia had brought out all the bottles and put them there, proving to the world that she was still organized and in control, though she must have had just as much to drink as Jen. Jen poured herself another glass of red and sat on the grass too. She told herself, and everyone else within earshot, that it had been years since she’d been to such a great party. Bloody years.

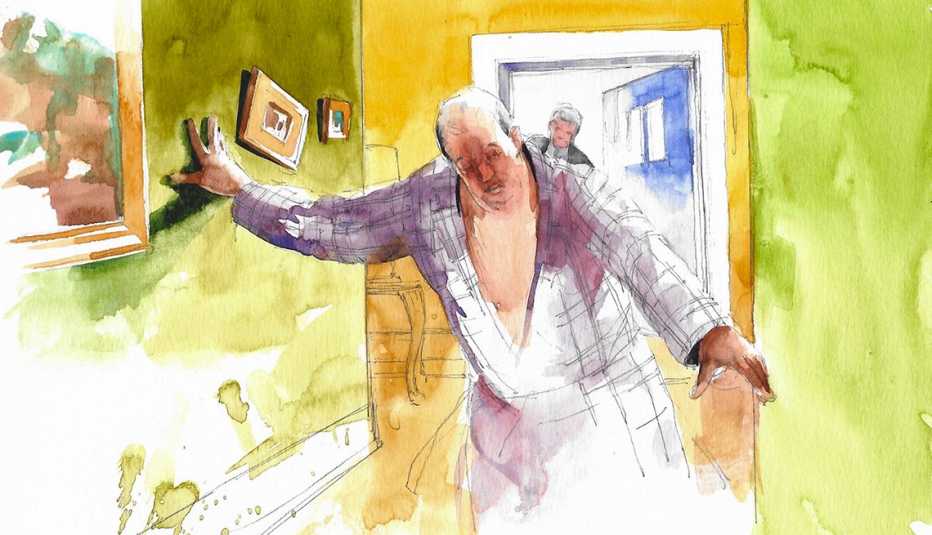

Later, only a small group was left close to the fire. Jen found herself talking to a middle-aged man, one of Cynthia’s neighbours. She’d seen him inside earlier, before they’d turned up the music, working the room, chatting politely to the other guests. He was small and sturdy, built like a troll from a fairy story, with a square head and short legs, and a wide smile that just prevented him from being ugly. Jen didn’t fancy him in the slightest, but everyone else seemed to have paired off, and she hated that sense of being the only single person in the group. Since her divorce the world seemed made up of happy couples. She even envied the ones who weren’t so happy. This man wore a checked shirt and walkers’ trousers, lightweight, easily dried. Jen could imagine him a member of a ramblers’ club. She thought he might be an accountant or a lawyer. Cynthia was a magistrate, sitting in the lower court, passing judgement on the petty criminals, the misfits and saddos, whom Jen was trying to convict, and she knew lots of lawyers. She and Jen had first met in court. Despite their different roles, they’d always got on. Cynthia’s husband was something important in the local hospital trust and she didn’t need a paid job.

Now, Jen was at that stage when she knew she’d had enough to drink, but she couldn’t quite stop. Her ex-husband had always said she had an addictive personality, the words spoken with a sneer and an edge of pity, just before giving her a good slap, and then blaming her for provoking him.

She thought Nigel had been holding the same glass of dry white for most of the evening.

‘So, Nigel. What do you do for a living?’ He’d already told her his name, slightly apologetically, as if it wasn’t a name to be proud of.

Nigel. Nigel Yeo. Yeo being a local name means he’s obviously from the West Country. Nigel ages him though. Who calls their kid Nigel these days?

Now she smiled, her best flirty smile. He might be older than she usually liked her men and was probably a boring sod, but chatting to him was better than sitting here on her own like a Billy No-Mates. Although Cynthia always said she shouldn’t try so hard and that the right man would come along eventually, Jen couldn’t bear the idea of being lonely for the rest of her life. Soon the kids would be flying the nest and she imagined her little house, as silent and cold as a grave, when she got in from work.

‘I work in the health sector.’ His knees were bent and she could see his shoes. Good quality, recently polished.

‘Oh, a medic?’ That made him more interesting. Jen might never want to think of herself as a snob, but she liked the idea of hanging out with a doctor.

‘Not any more.’ He smiled too, as if he knew what she was thinking, and again, there was something lovely about the smile, something that made up for the troll-like stature. ‘You could say I’m in the same line of business as you. Sort of. Though I’m more of a private investigator at the moment. In fact, there was something I wanted to discuss, but I’m not sure this is the right place after all.’ He seemed distracted for a moment. ‘Actually, it’s probably time for me to head home, I think.’ Nigel got to his feet, the movement smooth and easy, and wiped a few grass clippings from his bum. It was rather a nice bum too.

He hesitated when he was on his feet. ‘Is it okay if I get your number from Cynthia and call you?’

‘Yeah,’ Jen said. ‘Sure.’ She thought he might be suggesting a date and was flattered, almost excited, but it seemed he had something more formal in mind.

‘Work contact details will be fine if you don’t want to give me your personal number.’

She watched him walk away to say a polite goodbye to Cynthia. She felt ridiculously bereft, and that she’d missed an important opportunity for friendship.

The evening went downhill from there. She sat alone for a while with a beer, staring into the flames. When she saw Wes dancing slowly to music that he was humming and nobody else could hear, his arms round a woman young enough to be her daughter, she stumbled to her feet and walked home.

Chapter Two

JEN WOKE TO HER DAUGHTER BANGING on the door and shouting. She’d undressed the night before, but not bothered taking off her make-up; she could feel the mascara spiky on her eyelashes, see foundation and lipstick smeared on the pillowcase. So, she’d had a good night, but she hadn’t disgraced herself. Going to bed fully clothed was always a bad sign. Waking up with a stranger was even worse, but she only did that when the kids were in the Wirral with her ex’s parents. She’d never sunk so low as to bring a bloke home when Ella and Ben were here.

‘Yeah, come in, love.’ She pulled herself into a sitting position and looked at the clock by the bed. Ten o’clock, but it was a weekend and she wasn’t on duty, so no need to panic. She’d even been to the supermarket on her way home from work the evening before, so there was bread and milk for breakfast and they knew well enough by now how to scavenge. At least, she always thought when guilt stabbed her in the gut, more painful than heartburn, her kids wouldn’t grow up to be snowflakes.

The door opened and Ella came in. Sixteen, specky and skinny, at ease in her own skin. A science nerd, already in love with another geek, Zach, a lad from school, who bored the pants off Jen.

‘Don’t you want to go out and have fun?’ Jen would ask. She’d married too early and hated the thought of her daughter settling down too soon.

‘We are having fun.’

And they’d disappear off to Ella’s tidy room in the attic, not for drink, drugs and illicit sex, but to pore over chemistry homework or to watch some strange fantasy series on Netflix.

This morning Ella looked very young, still in her nightie, but the disapproval was obvious as she crossed the room to open the window. ‘It stinks in here. You need some fresh air.’ She could have been the parent.

‘Yeah.’ Jen ignored her thumping head. ‘Everything all right?’

‘You left your phone downstairs. It’s been ringing since I got up. Matthew Venn.’

‘Shit.’ Matthew Venn was the boss. The best boss she’d ever had, but he wasn’t much into fun either. He was a man of principle, still haunted, Jen thought, by a strict evangelical childhood. He could do disapproval as well as her daughter. ‘I stuck some clothes in the dryer before I went out last night. Can you fish them out while I jump in the shower?’

‘It was sunny yesterday. You could have put them on the line.’ More disapproval. Not content with saving her mother, Ella wanted to save the world too.

‘I know, but they don’t need ironing when they come out of the dryer. That saves power, doesn’t it?’ Jen pulled a face, which she knew would make her daughter laugh. There was an element of ritual to this exchange and El quite liked being superior.

Jen was already out of bed and on her way to the bathroom. She turned her voice into a wheedle. ‘And could you stick on the kettle, make some coffee? I bought some proper stuff yesterday.’

***

She phoned Matthew while she used the coffee to swallow two paracetamol. Ella had made toast too. There was no sign of Ben, who only ever emerged at lunchtime at weekends. Jen buttered the toast while she returned Venn’s call. If this was a shout, who knew when she’d next eat? ‘Sorry, boss. It’s my day off and I’ve only just picked up your call.’

‘We’ve got an unexplained death,’ Matthew said. ‘Ross and I are already at the scene. Westacombe. A group of craft workshops in the grounds of a big house.’ He gave her the postcode. He hadn’t said murder. He was always careful when he spoke.

‘I’ll be there as soon as I can.’ As soon as I’ve finished my breakfast.

‘You are okay to drive?’ She could hear him trying to keep the judgement from his voice but she knew what he was thinking: If you had a skinful last night, you might be over the limit.

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘Sure. See you soon.’

***

At least Westacombe was inland, and she was driving against the flow of the tourist traffic. She’d lived in North Devon for five years now and she’d become used to the narrow, twisting lanes, the high banks and hedges, which could hide sneaky tractors and oncoming traffic. She’d never quite got used to the summer traffic, though, to the endless streams of huge cars carrying children, camping gear and surfboards. The road climbed away from the coast and at one point, as she pulled into a lay-by to let a Land Rover and horse box go past, she had a view over the whole estuary — the two rivers, the Taw and Torridge, spilling into the Atlantic, glistening in the sunshine. This was her patch now, but she still missed the Mersey, with its ferries and the view from Birkenhead of Liverpool’s astounding skyline, with a passion that felt like bereavement. Classic soppy Scouser, she thought. You live as close to paradise as you can get but you’re still not satisfied, still dreaming of home.

The satnav on her phone directed her down a single-track lane; there was no room even for two small cars to pass. Grass grew in the middle of the road. She turned a corner and she was there. The lane fizzled out into a yard. There was a rather grand house, built of warm red brick, the same colour as Cynthia’s wall, but older, crumbling in places. It had two storeys and, above them, what must be attic bedrooms, with little dormer windows built out of the slate roof. To one side of the yard a cottage. On the other a large barn. There was a row of smaller outbuildings with stable doors. This was one complex, but with multiple uses, all converted from the original farmhouse and farm buildings. Jen knew this because as she’d driven into the yard, she realized she’d been here before. Westacombe was less than three miles from the busy seaside village of Instow, but felt entirely cut off, a world of its own. That was what she remembered: the sense of having wandered into somewhere a little magical and not quite real.

She’d only visited once, but she hadn’t forgotten it. The visit had felt like an act of transgression, but also a celebration of freedom, of getting her life back. She’d never had a wild, irresponsible youth and this was as close as she’d got. Wes had brought her one Easter when the kids had been staying with their grandparents in Hoylake. Jen had been fretful and tense, anxious that her ex’s mother and father were poisoning her lovelies with stories about her fecklessness, her inability to look after them properly. Not that Robbie, her former, unmissed husband, had wanted them full-time. He’d never made a claim for custody. He liked his new, single life too much for that. Ella and Ben never stayed in his grand apartment in the old Albert Dock during their increasingly irregular visits, but instead with Reg and Joan in their Victorian villa by the coast in the Wirral. Robbie deigned to call in occasionally to meet his children. When work and his private life allowed. Sunday lunch was a favourite time. Nothing much happened in his world at Sunday lunchtime and his mother was a decent cook.

It was the first time she’d met Wes. Cynthia had invited her out. ‘You can’t stay at home brooding when you’re free from parental responsibility at last.’ She’d taken Jen to a bar right on the beach in Instow. ‘There’ll be jazz. I’ll introduce you to a few people.’ It had been small, dark, crowded, owned by a middle-aged Scot called George, who introduced the musicians as if they were all his best friends. Checked tablecloths and candles in bottles. A fishing net hung from the ceiling. Kitsch, but in a self-conscious sort of way. Jen had been intimidated by the music and the people, who, in the silences between songs, talked about books she’d never read and films she’d never seen. So of course, she’d drunk too much, become too loud, too chatty. Wes had been in the audience that night, not playing, though Jen had been able to tell he was a regular; he knew all the bar staff, and George treated him indulgently, as if he were a son who’d gone slightly off the rails. When Cynthia and her chums talked about heading back to Barnstaple, Wes had taken Jen’s hand.

‘Stay for one last drink. We can get you a taxi home.’ They’d walked on the beach in the moonlight and her head had been spinning as they’d looked up at the stars. When the taxi had arrived, it had taken them to Wes’s place, to this house, where he had a couple of rooms in the attic. Jen, of course, had paid the fare. It only occurred to her now, as she climbed out of the car, that the unexplained death might relate to Wes.

Matthew and Ross were standing in the yard, suited and booted like the CSIs, but recognizable, even in their paper suits and masks. Matthew was upright, almost military in stature, and his eyes were as grey as granite. Ross May was as skinny as a whippet and fidgeted like a child. She joined them, took a suit for herself, and while she was climbing into it, spoke to Venn.

‘Male or female? I’ve been here before and know one of the guys who lives here. Or who used to live here. He might have moved on. It was a couple of years ago.’ It was best to let Venn know how things stood before the investigation developed.

‘Male,’ Matthew said. ‘What was your friend’s name?’

Jen was going to say that he wasn’t a friend, not really, but that would have been protesting too much. Besides, Matthew liked straight answers.

‘Wes,’ she said. ‘Wesley Curnow.’ She hesitated for a moment. ‘Actually, I saw him last night.’

Matthew shook his head. ‘That’s not the name.’ He looked at her. ‘What do you know about this place?’

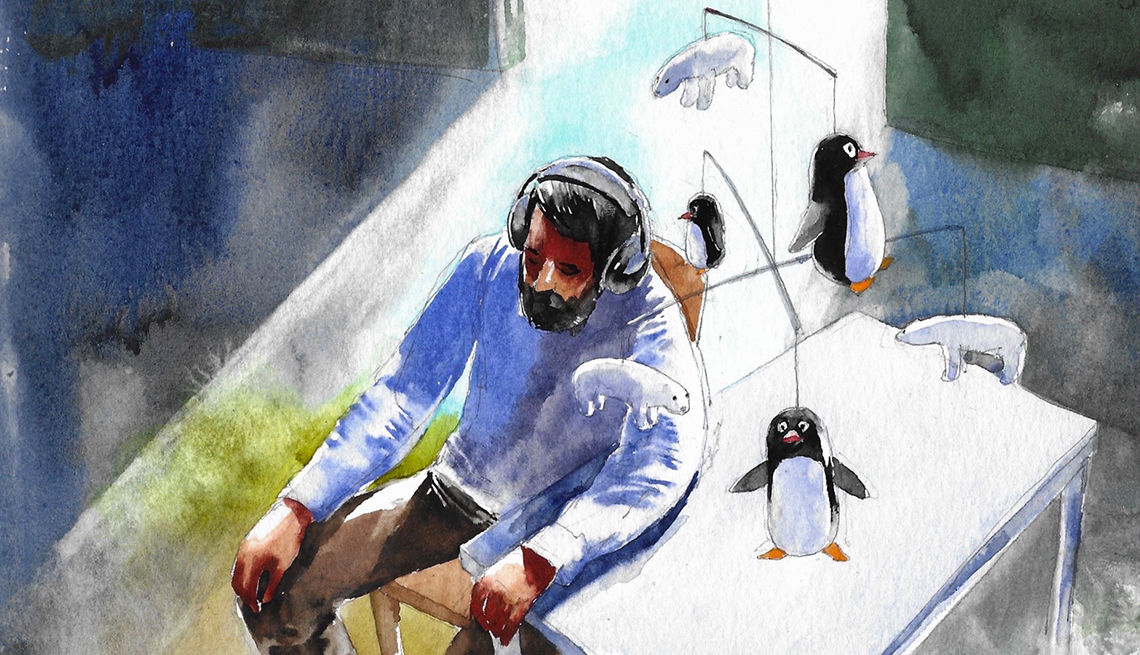

Jen shrugged. ‘I only came here once.’ The morning after hooking up with Wes, he’d made her breakfast in a large, untidy communal kitchen on the ground floor. Flagstones on the floor and an Aga pockmarked with grease. Another hangover. More coffee and bacon sandwiches on fresh white bread, dripping with fat. A couple of other people had drifted through, but she’d not taken much notice of them. Wes had been the focus of her attention. He’d been barefoot, in tatty jeans and a loose T-shirt. Even with the hangover, she’d been smitten. He’d been a kind and thoughtful lover, and that had been a novelty for her. Even now, she found a smile drifting across her face as she remembered the night. ‘It’s a kind of artists’ commune. The owner lives in most of the house, but he rents out a couple of flats in the attic to crafts people and they have their workshops here too.’

Ross sneered, seemed about to say something cutting about artists or communes, then thought better of it in front of the boss. He was learning.

Jen went on: ‘The guy I know makes recycled furniture, driftwood sculpture, that sort of thing. He’s a musician too. Jonathan will probably have come across him.’

Matthew nodded. Jonathan, his husband, managed the Woodyard, a large and successful community arts centre in Barnstaple. He mixed in such Bohemian circles. The Woodyard wasn’t Matthew’s natural home, but he was learning too, and making more of an effort to get on with Jonathan’s friends. Perhaps because of his evangelical upbringing, Matthew found it hard to consider an activity that was fun, creative or exciting as real work. He’d joined the police service because it provided the sense of duty and community that he’d missed when he left the Brethren. Jonathan sometimes mocked him because he took himself so seriously. He turned his attention back to his colleagues. ‘Shall we see what we’ve got, then?’

Jen tucked her hair inside the paper hood, pulled on her mask and followed him. A row of farm buildings had been turned into studios and workshops.

‘Who found our victim?’

‘His daughter, Eve. She lives and works here. She’s a glass blower. She found him in her studio at eight thirty this morning.’ Matthew paused. ‘The cause of death is obvious enough apparently, but Doctor Pengelly is on her way.’

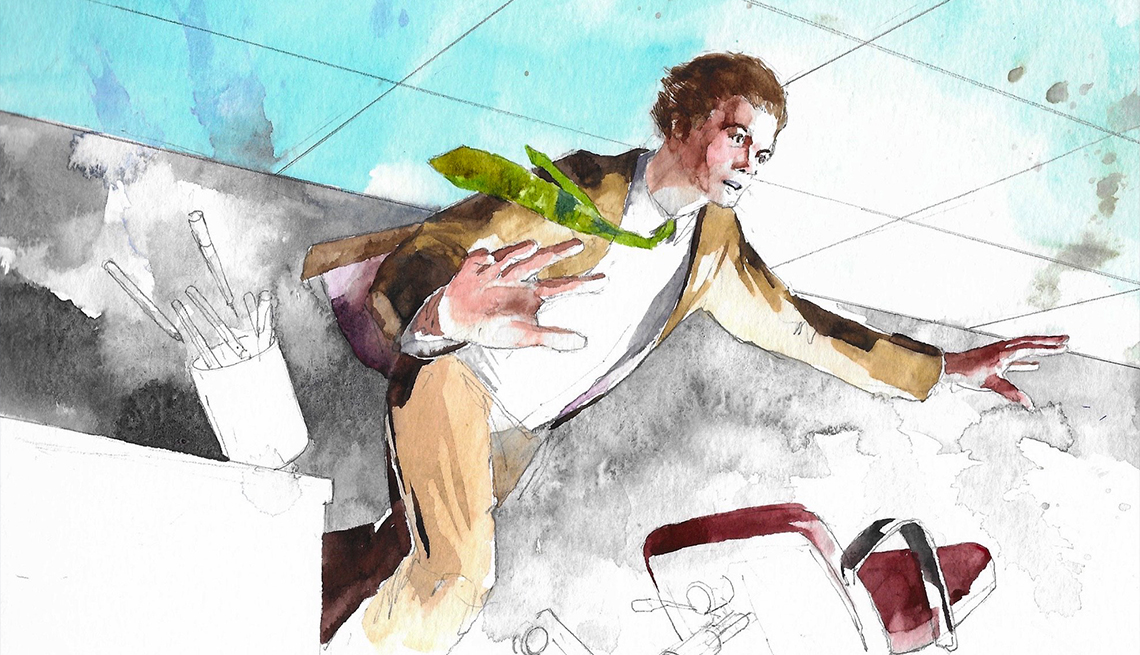

There was a stable door leading directly from the yard into one of the outbuildings, a long, low room. Jen was expecting the space to be dark and claustrophobic, but much of the roof had been replaced by a skylight and sunshine was flooding in. It was almost unbearably hot. The heat seemed to be coming from a furnace in the corner. Jen wondered why nobody had thought to switch it off, but of course, nothing could be touched until the CSIs had finished their work. Getting closer, she realized that the furnace wasn’t lit, but must still be hot from the day before. On the wall there were racks from which a series of long metal pipes, a steel shovel with a square, box-like end, and a flat-bladed shovel dangled. There were shelves containing devices and objects which could be instruments of torture: pincers and tongs, and a couple of blowtorches.

The whole place had the air of a torture chamber. Jen thought it resembled an image of hell, as described by one of the more imaginative nuns who’d taught her. A man was lying on his back in front of a polished workbench, caught in the sun’s rays. He was surrounded by shattered glass and a shard, as long and sharp as a knife, had pierced his neck. There was blood. A lot of blood, spread all over the floor and spattered on one of the walls.

‘So, it seems that he was killed where he was found,’ Matthew Venn said.

Jen hardly heard her boss speaking. ‘I know him,’ she said. ‘At least, I’ve met him. Last night. I was at a party at Cynthia Prior’s place and he was there. His name’s Nigel Yeo.’ She paused. ‘He works for an organization that monitors the health authority. Something to do with investigations. He wanted to talk to me, but said it could wait.’

‘He wanted to talk to you professionally?’ The workshop door was still open and they were standing just inside. Matthew had turned towards Jen.

She shrugged. ‘That’s what I thought he meant. But it was a party. I’d had a few drinks. You know what it’s like ...’

But Matthew wouldn’t know what it was like. He drank very little and certainly would never lose control. Jen tried to imagine him going to bed, too drunk to take off his clothes, but the idea was ridiculous. She looked again at the body, remembered the heavy smell of honeysuckle in Cynthia’s garden, the kind smile, and found herself feeling a little faint. ‘He seemed like a kind man.’

‘His daughter, Eve, is in the kitchen. If you’ve been here before, you’ll know where it is. Go and take an initial statement, while things are still fresh in her mind.’

Jen nodded and went out into the yard. She stood for a moment taking deep breaths. The sun was already hot. The kitchen was cooler, though. There were still stone flags on the floor but the range she remembered from her previous visit had been left to go out. A new electric cooker stood in one corner, and the room seemed cleaner, tidier; otherwise, little had changed. A woman in her late twenties or early thirties sat at the table. She was wearing dungarees and a striped T-shirt, red sandshoes. To Jen’s relief she was alone. There was no sign of Wes.

‘Eve?’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members