Staying Fit

Twenty-five

Matthew

IN THE CLOAKROOM they started talking about the millennium. Heather’s mother, an accountant, claimed that everything was going to crash at midnight on December thirty-first. “But there must be safeguards,” Matthew said. The idea of massive disruption was disturbing and thrilling: Big Ben with both hands stuck at twelve; trains running randomly; the Co-op giving out free food. Tim said there were safeguards, but some hacker in Moscow could topple the whole system. Raj said the important thing was not to fly on New Year’s Eve. By the time Matthew collected his jacket and retrieved his books, the bus had left. He decided to visit Rachel. Between fencing lessons and his search with Tomas, they had scarcely seen each other for a fortnight. With luck, her mother would still be at work. He half walked, half ran through the darkening streets, knocked on her door, and stood back. Maybe he’d pretend to be collecting for Oxfam. The door opened.

“Hi, I was—”

Something was wrong. Her eyes were too wide, her mouth too tight. “Matthew, what are you doing here?”

His presence had never before needed explanation. “Can I come in?” He smiled, hoping she would do the same.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

“Benjamin’s here.”

She could have added several things to that simple sentence. They were studying. He was borrowing a book. But none would have given more information than those two words and the way she stood, blocking the doorway. He turned and ran into the street. As he hurtled down the pavement, his footsteps drummed out the syllables: Ben-ja-min, Ben-ja- min. How could his friend do this? What had he done to deserve this? He took refuge in the bus shelter where, a week ago, he had stored donations for Oxfam. The bench was cold and damp; from the shadows beneath rose the smell of old chips. In the midst of trying not to shiver and trying not to breathe, he had one clear thought: he could not go to school tomorrow.

He didn’t notice the car pulling up at the curb until the door opened. “Want a lift?” his father said. He settled gratefully into the odorless warmth. As they headed out of town, his father asked if something was wrong.

“I had a row with Rachel.” Did two words count as a row? “We’ve broken up.” He understood the cliché in a new way.

“I’m sorry. And right before Christmas, with lots of parties.”

He hadn’t thought about that. Night after night he, Benjamin, and Rachel would find themselves in dimly lit rooms filled with music and mutual friends.

“Breakups are hard,” his father was saying. “Time is the only thing that helps. When I was your age ...”

Suddenly he worried that his father might be about to confess his own romantic difficulties. Even in the midst of his misery he knew this must, at all costs, be avoided. As long as the woman was unspoken, she would have to be fitted into the small spaces left over from work and family. Any mention of her would be a step toward allowing her to take up more room. Desperately he began to talk.

“We didn’t just break up. She was with Benjamin. We’d never have got together in the first place except for him. He was the one who told me to invite her to a film he knew she wanted to see. Who told me she was interested in recycling and stuff.”

“Christ. No wonder you’re gutted. Your girlfriend and your best friend. Are you sure? Benjamin’s the last person I’d have expected to behave like this.”

A dark shape scampered across the road, a vole or weasel dashing to safety. “They were there together,” he said. “They wouldn’t let me in. I keep telling myself that Rachel wasn’t perfect. She went on and on about the Green Party, and a couple of times she wasn’t nice to Duncan.”

“People are allowed to be boring,” his father said, “but everyone should be nice to Duncan. Sometimes when I’m about to lose my temper, I think, Could I tell Duncan what I’m about to say? Last week ...”

He began to describe a client who kept changing his mind about a fire screen. Matthew managed to say just enough to keep the conversation going until they reached home.

***

LYING IN BED, HE PARSED the morning sounds—voices, doors, dishes, toilets—of which he was usually a part. He heard footsteps outside his room and a faint rustling. A sheet of paper slid under the door. A few minutes later, another followed. When the front door closed for the last time and his mother’s car coughed to life, he retrieved the notes.

The first was from Zoe: Hope you feel better. Let’s plot REVENGE!!!

The second from his mother: Dear Matthew, there’s soup on the stove, and the usual things for sandwiches. You need to go back to school tomorrow, so try to figure out what will make that bearable. See you this evening. Love, Mum. P.S. You’re a star.

Downstairs in the parlor he retrieved a cardboard box. He circled his room, gathering up reminders of Rachel: photographs, a cinema ticket, a scarf she’d knitted, prophetically already unraveling, a T-shirt from a concert, a note signed with kisses. He taped the box shut and wrote Private. Do Not Open on the side. But where to put it? He couldn’t bear the thought of it in his room, and Zoe, if she found it, would open it immediately. Finally he carried it to Duncan’s room and pushed it under the bed.

When he woke again, his priorities were clear. The person he needed to talk to was Benjamin, his friend since their primary school teacher had put them in charge of the class begonia, his friend who had said of course she likes you and who had endured many afternoons of doing homework and hanging out with Rachel, his presence both superfluous and essential. And then, when Matthew and Rachel finally got together, his un-complaining acceptance of their need for privacy. As for Rachel, he told himself firmly, she was pretty, she was good at chemistry, she had opinions, but within a hundred miles there must be a hundred similar girls. It was his liking that had made her special.

Could he hold on to this insight? Only, it turned out, for a few minutes. Then the noose of misery tightened again. He remembered her shyly showing him a new dress, paddling in the river on a rainy day. All those hours of talking, and doing it, were not going to vanish so easily.

Downstairs he made tea and toast and forced himself to contemplate tomorrow. He and Benjamin shared every class but one. Together they moved from history to French to algebra; later there was debating club and, on Thursday, fencing. He had never asked himself, Does Benjamin like me? Or do I like him? Their friendship was a given. As he showered and dressed and did homework, he clung fast to this thought. When Zoe came home, he asked her to phone him and arrange a meeting.

“The Green Man at six?” she suggested.

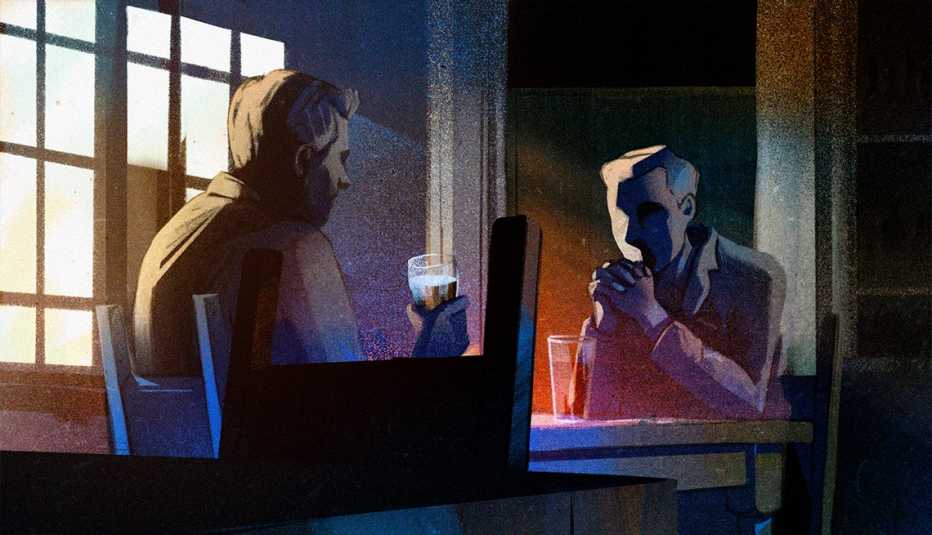

A pungent memory of Tomas made him say no, the Hare and Tortoise.

A few minutes later she was back; Benjamin would be there. Sitting cross-legged on the end of his bed, she said, “Are you going to have a fight? Whatever’s going on with him and Rachel, it won’t last. He’s too clever, and too nice.”

“He’s not very nice at the moment. What makes you such an expert on romance?”

She pouted. “Statistically most teenage relationships don’t last. Unstatistically, Rachel has wandering hands. Remember Mr. Datta, the cricket coach last spring? She was all over him.”

“You never told me that.”

“I didn’t want to make trouble. Besides, nothing happened. Were you really in love with her? I thought you just wanted to sleep with her.”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members