Staying Fit

“We always say, ‘Let’s go see Hugh,’ when we head to the 17th hole,” the golfer explains — the Hugh in question being my great-great-great-great grandfather, Hugh Steers, who fought in the Revolutionary War. He rests mostly peacefully in a wooded patch of land amidst a northern Kentucky golf course, in a grave decorated with flags and plaques placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Because I am from a small family — one brother, one cousin on each side, and no offspring among us — I’ve found it comforting to reach back in time for additional family. Visiting places where my ancestors lived gives me a visceral connection to the flow of my history. I especially wanted to explore this area of Kentucky, knowing that grandfather Hugh had returned to live near the very place he was captured and held prisoner for two years by Native Americans fighting for the British.

After paying homage at Hugh’s golf course grave, I drive to the nearby hamlet of Big Bone, because the odd name sparked my interest when I discovered it on my ancestor’s census record. I’d soon learn that Big Bone, sited in a protruding knob of Kentucky across the Ohio River from the Indiana-Ohio border, was named after mastodon, mammoth, giant sloth and other ancient bones unearthed from a salt lick.

Specimens from Big Bone caused a stir in the late 1700s and found their way into collections of Benjamin Franklin, the King of France and Thomas Jefferson, who sent William Clark (minus his other half, Meriwether Lewis) to collect more. Jefferson thought these mysterious giant beasts still roamed the West, and he hoped the Lewis and Clark Expedition would find them.

Today the surroundings are part of Big Bone Lick State Park, where some truly big bones are on display. Hiking a park trail, I inject myself into Grandpa Hugh’s past, amid the rolling, wooded landscape. When I discover a worn shard of patterned pottery by a creek, I imagine it may have come from my super great-grandfather’s era.

As I continue exploring the region, I can see what attracted early settlers here: The land is rich and loamy, water is plentiful and the nearby Ohio River was a vital highway of navigation. But why did Hugh return to live just a few miles from where he was captured in a battle known as Lachry’s Defeat? At a spot now marked by a monument, Native Americans attacked his group of Pennsylvania volunteers as they headed down the Ohio by boat. Visiting the Indiana site, I try to conjure the disastrous scene where all of Lachry’s 107 soldiers were killed or captured.

I learn that the Mohawk commander, Joseph Brandt, was schooled in English and the classics, had traveled to England and was presented to King George III. That’s mind-blowing considering Hugh made his “mark” on documents I’ve found online — meaning he couldn’t read or write.

Friendly innkeeper

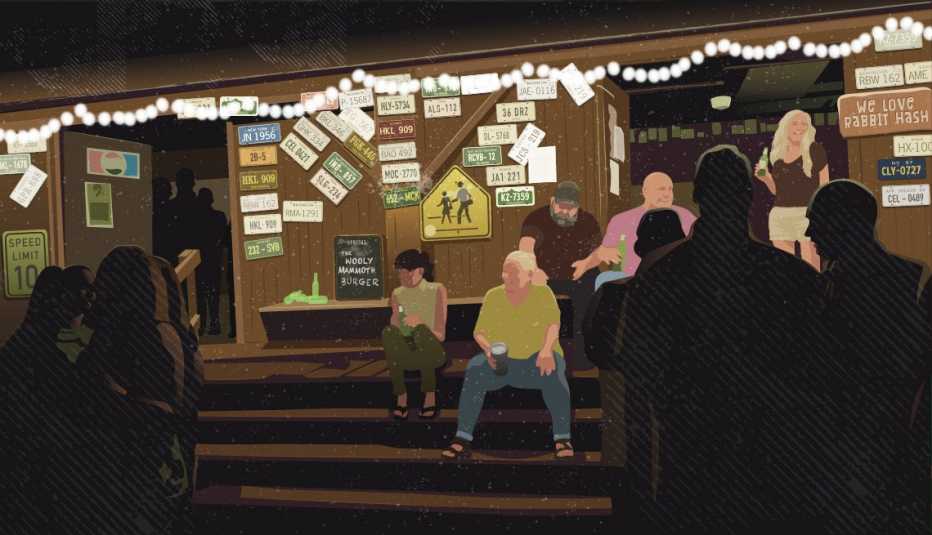

When looking for a place to stay during my visit, I’d spotted another Kentucky village near Big Bone with its own quirky name: Rabbit Hash. An apartment called the Old Hashienda was available for nightly rental. The whimsical name alone fished me in, but I also discovered it was located across the street from the Rabbit Hash General Store, established in 1831. Maybe Hugh shopped there?

Rabbit Hash, population 1.5 (the .5 resides there only half the year), is a 3-acre clutch of wooden buildings beside the Ohio River, including a log cabin housing a small museum, a barn where monthly dances rock the countryside, and the Old Hashienda, which shares its location with the Verona Vineyards tasting room.

You Might Also Like

The Joys of Traveling with a Grandchild

A New Mexico road trip provides precious memories and lots of time for intergenerational bonding

Author Finds Long Road Trip Opens Door on Serious Qualms

How a getaway to Key West helped one couple resolve some long-standing differences

More Members Only Access

Watch documentaries and tutorials, take quizzes, read interviews and much more exclusively for members