AARP Hearing Center

The body of a man is found on the shore of North Devon, a picturesque tourist county in England. The main identifying mark is an albatross tattoo on his neck. With this, The Long Call begins and promptly takes readers through a winding mystery full of secrets, lies and an ever-changing list of suspects.

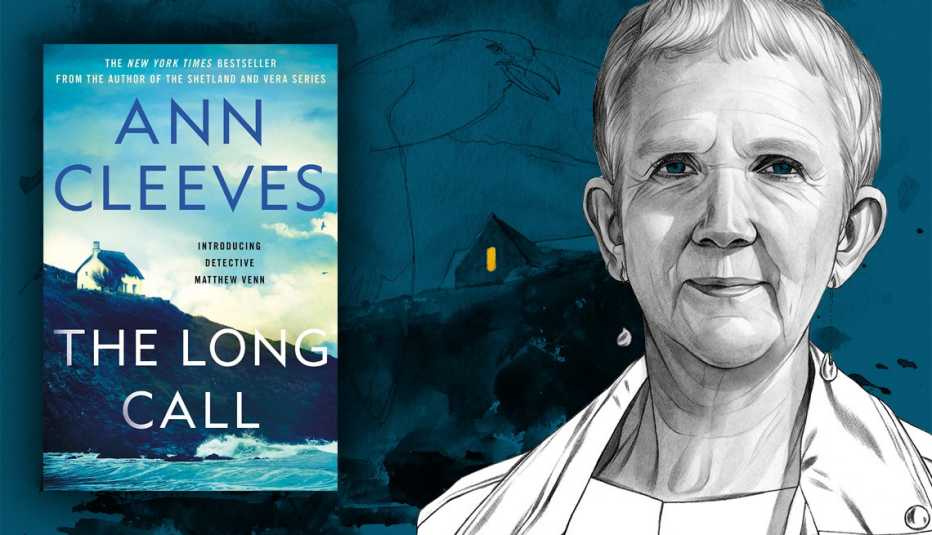

Best-selling British crime author Ann Cleeves was inspired to write The Long Call after visiting North Devon following the death of her husband, Tim Cleeves. Needing a change of scenery and being back in the place she lived as a teenager swirled memories and prompted conversations, bringing her reflections to the page. The Long Call introduces Detective Inspector Matthew Venn and launches the Two Rivers series, a collection that mystery readers will sink into.

Cleeves, who’s been writing for decades, is best known for her Vera Stanhope and Shetland Island Mystery series — both of which have been turned into popular TV dramas. (And, no surprise to her fans, The Long Call was an instant New York Times best seller and has already been optioned for TV by Silverprint Pictures, the company that produced Vera and Shetland.)

For the author, writing came easy — a small joy she could fit in while she and Tim raised their daughters. Her first book, A Bird in the Hand, was published in 1986 and kicked off a series that followed retired naturalist George Palmer-Jones, who quietly looked into a murder.

“I wrote a mystery because I discovered I wasn’t very good at plotting, and the traditional detective story provides a useful structure!” she says. “Mysteries were also my comfort reading, so I understood the form very well.” A Bird in the Hand wasn’t a standout success, but it boosted her profile and confidence.

“I love doing it, it’s just telling stories,” Cleeves says. “I made enough to be able to take the family on holiday because I built up a small readership, and libraries would stock me. But you would never see any of my books in the main chains. I assumed it was how it was always going to be, and that was fine. I wasn’t doing it for the money — I just loved the ability to tell a story.”

More From AARP

Free Books for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety online for AARP members