Staying Fit

Editor's note: Americans may not see eye-to-eye on many things, but fully 96 percent of us agree on the importance of Social Security. And no wonder: The program, now 87 years old, has become the bedrock of our retirement finances. Which begs the question: Why are its finances not more secure? To answer that, AARP talked with dozens of experts about Social Security and its future viability. Here’s what we learned.

For decades, financial advisers have used the metaphor of a “three-legged stool” to describe America’s retirement system: that the equation for late-life security is having a healthy pension from work, ample personal savings and a monthly Social Security payment.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

So much for that. Pensions that guarantee income for life are a dying breed in America, and too few Americans have accumulated a nest egg that can provide substantial monthly income across the full expanse of their retirement years. Less than 7 percent of retirees today have steady income from all three “legs of the stool,” reports the National Institute on Retirement Security.

Of those income streams, only Social Security has proven steadfast and strong. Not only is it the largest source of income for most retirees, but it also has never missed a monthly payment since it cut its first check to Ida May Fuller in 1940. Which is perhaps why so many Americans are anxious about its health. A 2020 AARP poll showed that 57 percent of Americans are not confident in the future of the program.

“Those who tend to distrust the government seem to have less faith that Social Security will be there for them in its current form,” said Michael Baughman, a financial planner in Tryon, North Carolina. “And as you work with younger clients, there is even less confidence in Social Security.”

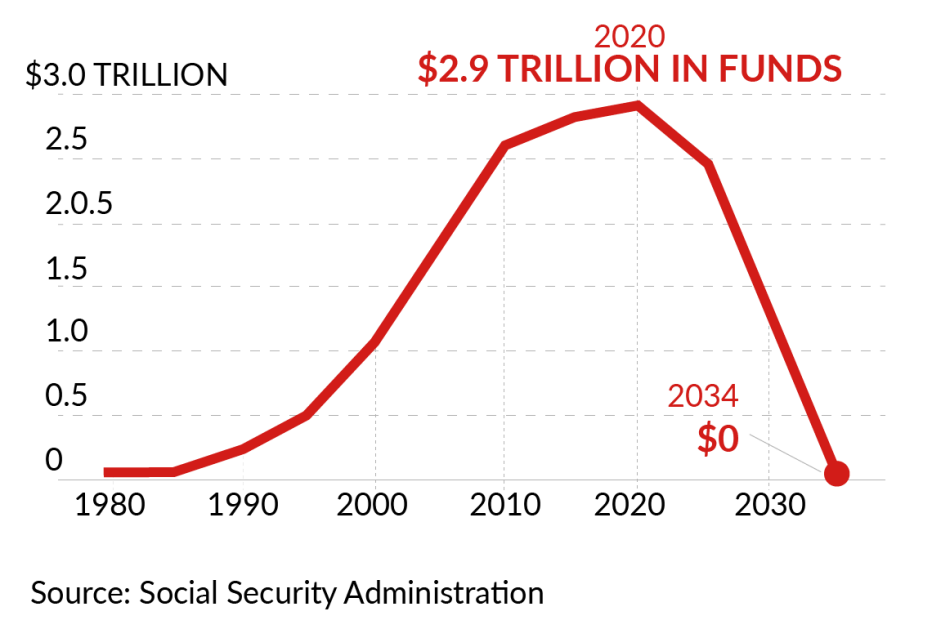

While worry about the program is hardly new, with younger Americans typically more doubtful than older, the skeptics do have a point. Social Security’s finances are unquestionably on a downward slope, and fixing them is primarily in the hands of the U.S. Congress. If no action is taken, the moment of crisis — meaning when the program would no longer have enough money to fully pay its promised benefits — will happen in just over a decade.

Although there’s plenty of reason to suspect that Congress will drag its feet, it is likely that pressure will build to act before that moment. But it could be awfully close to the deadline. “Any reform that’s politically feasible requires things that both parties hate,” says Reid Ribble, a former Republican congressman from Wisconsin’s 8th District. “Republicans have never wanted to increase revenue, and just dealing with it on the benefit side is not politically feasible.”

Popular and troubled

Social Security is one of the most successful anti-poverty programs this country has ever created. Without Social Security benefits, 21.7 million more Americans would be below the poverty line, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Social Security does more than send eligible retirees a payment every month. It provides ongoing income to surviving spouses and their children as well. Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) helps pay the monthly bills for qualified disabled workers and their families. Although most of those whom Social Security keeps out of poverty are older adults, 6.9 million are under age 65, including 1.1 million children.

Not surprisingly, Social Security has widespread support. “It’s crystal clear that Americans of all generations value the economic stability Social Security has offered" since 1935, says Nancy LeaMond, AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer.

But there’s trouble on the horizon. Absent any change in law, the Social Security trust funds — the financial accounts that the program draws from when annual payments to Americans are larger than annual tax collections — will be out of money in 11 years, according to the latest annual report from Social Security's trustees. At that point, the program would have only ongoing tax revenue with which to fund payments; calculations show that would cover only 80 percent of promised benefits.

To Congress, 2034 is a long way off. But the sooner the legislature acts, the quicker and easier it will be to bolster the trust funds’ reserves, due to simple math: Smaller revenue or benefit changes made now would accrue over time, which is a far more efficient way to secure the funds than paying for a last-minute major repair job.

More Social Security Answers

AARP’s Guarding Your Health and Financial Well-Being

Biggest Social Security Changes for 2022