AARP Hearing Center

The sun was shining bright. Just the right amount of fluffy clouds were floating in the sky, and birdsong filled the air. It was what most would call a typical summer day in Haleʻiwa Town, on Oʻahu’s North Shore. In Hawaiʻi, visiting my daughter, I’d planned to go snorkeling and, hopefully, catch a glimpse of a Hawaiian green sea turtle (honu) before boarding a red-eye flight back to Northern California. That changed when every cellphone in the house started shrieking.

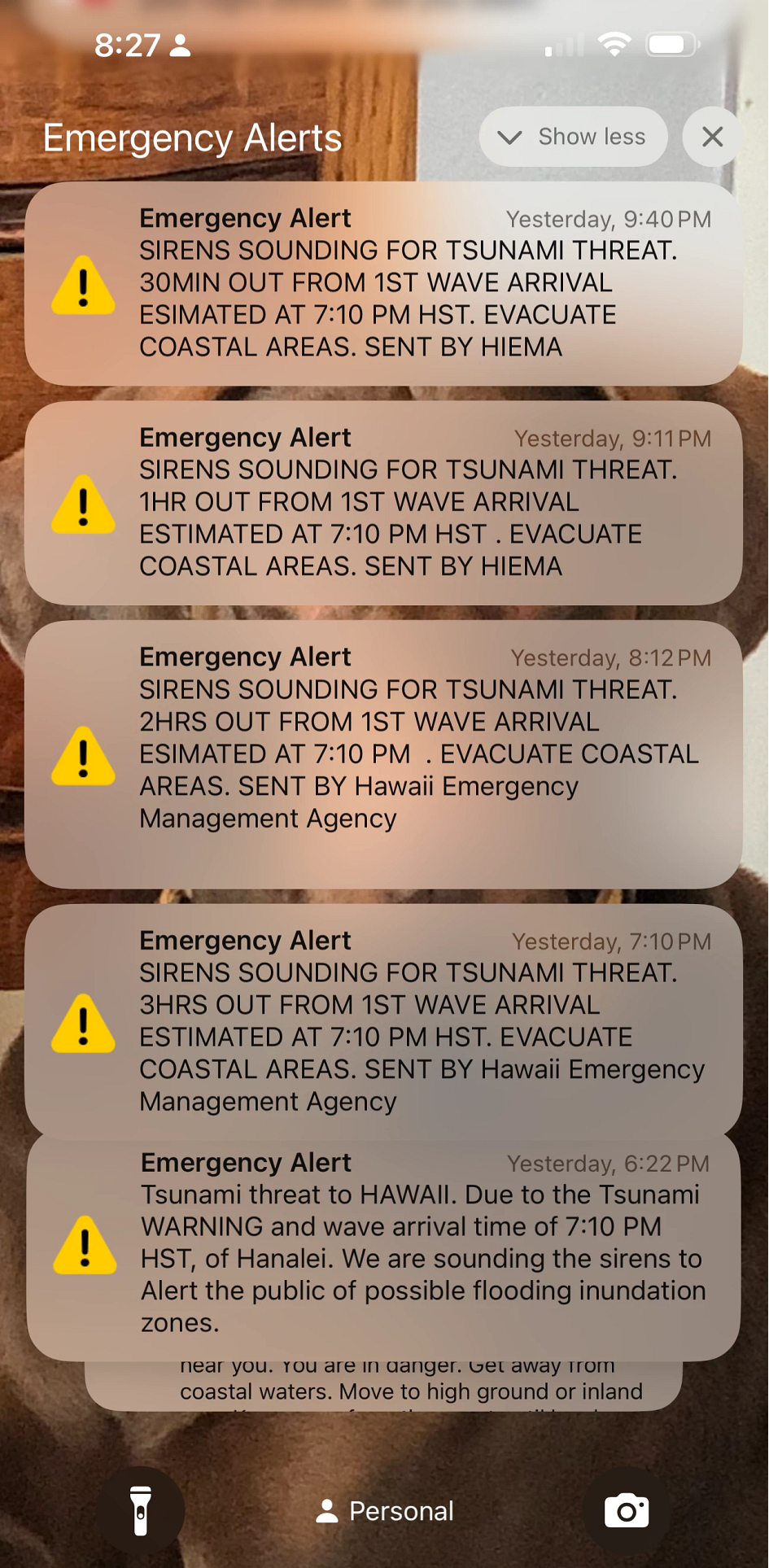

On July 29, after one of the strongest earthquakes ever recorded struck off the coast of a peninsula in far-eastern Russia, my family was among the millions around the world ordered to evacuate because they were potentially in the path of waves from tsunamis, according to the Associated Press. Luckily, my suitcase was already packed. While my daughter gathered clothes, medications and important documents such as her passport, I moved swiftly around the house, closing windows and raising anything that could be easily moved off the floor, to minimize damage from possible floodwaters.

Moving walls of water, tsunamis can flood more than a mile inland; we knew we had to move quickly and were ready to evacuate shortly after the first round of Hawaiʻi’s outdoor siren warning system cried out.

I was raised on a barrier island off the coast of southern New Jersey and now live in Northern California wine country. Throughout the past five decades, I’ve faced evacuations because of hurricanes and, most recently, wildfires. Traffic was our biggest obstacle to reaching safety. Even in the best conditions, there can be delays on the pair of two-lane highways that stretch through inland Oʻahu to the remote North Shore, caused by folks visiting famous surf breaks and other popular sights.

Within minutes of leaving my daughter’s driveway, we were queuing to crawl through a roundabout. At a time when frustration and road rage would have been expected, I can’t recall a single honking horn. A feeling of courtesy and understanding — that we were all in this together — prevailed. Drivers yielded to one another; “shakas,” Hawaiian hand signals expressing goodwill, where your middle fingers are curled, and thumb and pinkie finger extend outward, were thrown generously.

More than an hour later, when my daughter and I made it to higher, inland ground at a family friend’s house, every fast-food restaurant we passed was closed, so we stopped at a grocery store for dinner supplies. A steady stream of folks was coming and going, picking up water, Spam and other essentials, but no one appeared to be clearing shelves.