Staying Fit

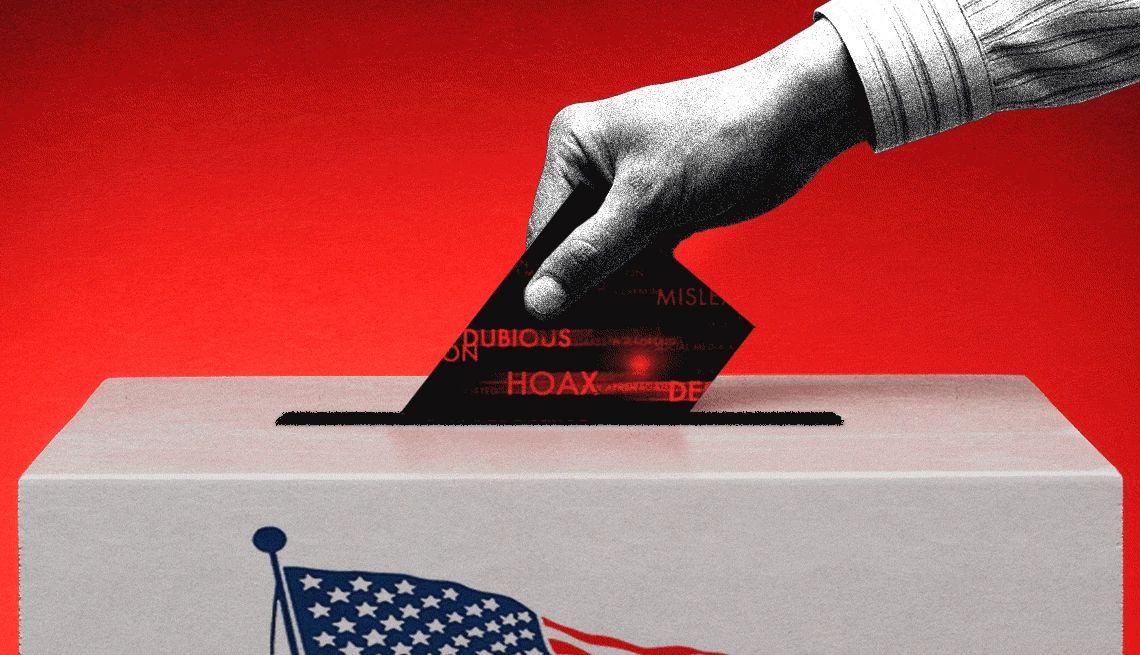

Government & Elections

Read news and features on government, politics, voting and vital issues 50-plus Americans care about — from Medicare to Social Security to the economy

Voter resources

AARP Issue Briefs

AARP IN YOUR STATE

Find AARP offices in your State and News, Events and Programs affecting retirement, health care and more.