AARP Hearing Center

Italian culture has practically trademarked the concept of la dolce vita, a phrase translated as “the sweet life.” But Italians also specialize in a related custom called dolce far niente, literally defined as “the sweetness of doing nothing.”

Decades ago, as a boy, then as a teenager and young man, I excelled at doing nothing. My mastery of idleness bordered on genius. I could easily lie on a beach all summer long without budging, much less feeling guilt.

But my attitude about expending energy shifted in my mid-30s. I had a wife and two children to support. I finally grew a conscience and adopted something unprecedented for me, namely an operative work ethic. From then on, I rarely took my foot off the gas pedal, my eye always on how to propel myself to a better job and a bigger salary.

Fast forward 35 years. I moved from New York City to Southern Italy. I now live in an ancient hillside town named Guardia Sanframondi. I have no plans to retire and can afford to tap my brakes. But I nonetheless aspire, at age 72, to bring myself full circle. I wish to learn anew how to practice dolce far niente.

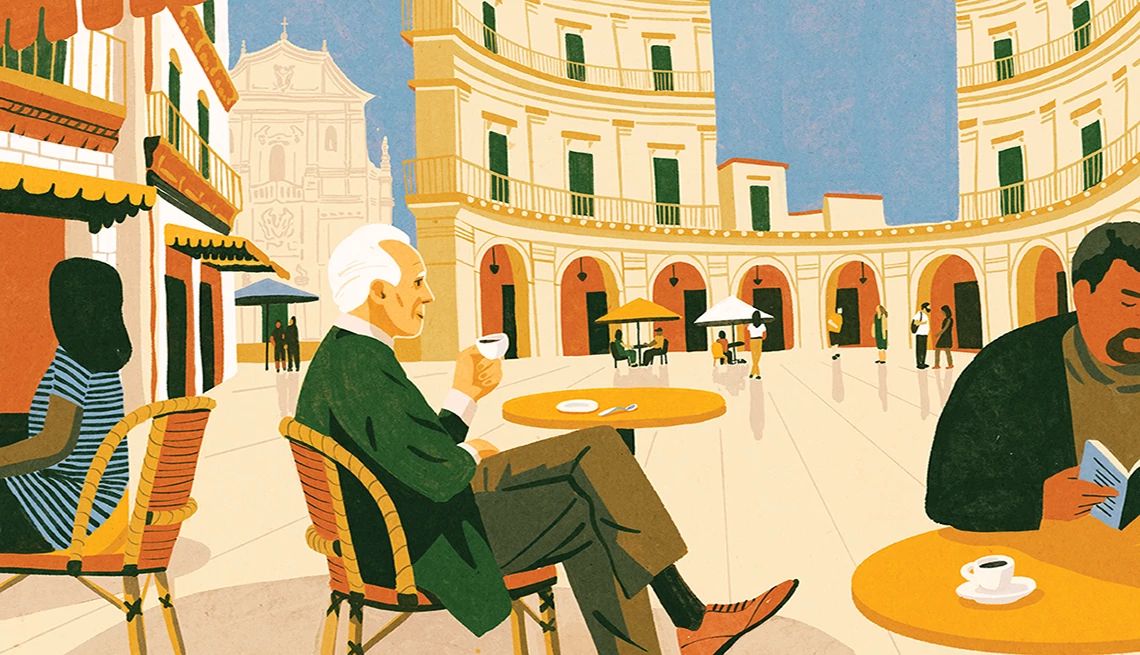

This philosophy is generally interpreted to mean slowing down enough to come to a standstill and indulge in embracing the smallest, simplest pleasures of life. It could mean daydreaming under a tree in the countryside or sipping cappuccino in a café watching people parade past. The origin of the term is credited variously to the poet Lord Byron, the Italian adventurer Casanova and the Roman writer Pliny The Younger, who wrote, “It seems ages since . . . I knew what it was to do nothing, and rest and enjoy that lazy but delightful state of inactivity where you hardly know you exist.”

As it happens, Americans are evidently getting better at it. We now devote more time than ever before, if only slightly, to “relaxing and thinking.” So found the most recent Time Use Survey from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), released in June 2024. Examples of activities the BLS fits in this category range from “goofing off,” “wasting time” and “hanging around” to “breaks at work,” sunbathing, sitting in a hot tub and “reflecting, daydreaming, fantasizing, and wondering.”

You Might Also Like

5 Things I’ve Discovered From Dating Younger Men

First off, they’re often attracted to you because of your age

How Wayne Wong Helped Invent an Olympic Sport

More than 50 years after freestyle skiing began, he continues to refine it

A Place for My Father’s Ashes

A daughter's story of loss, grief — and release