AARP Hearing Center

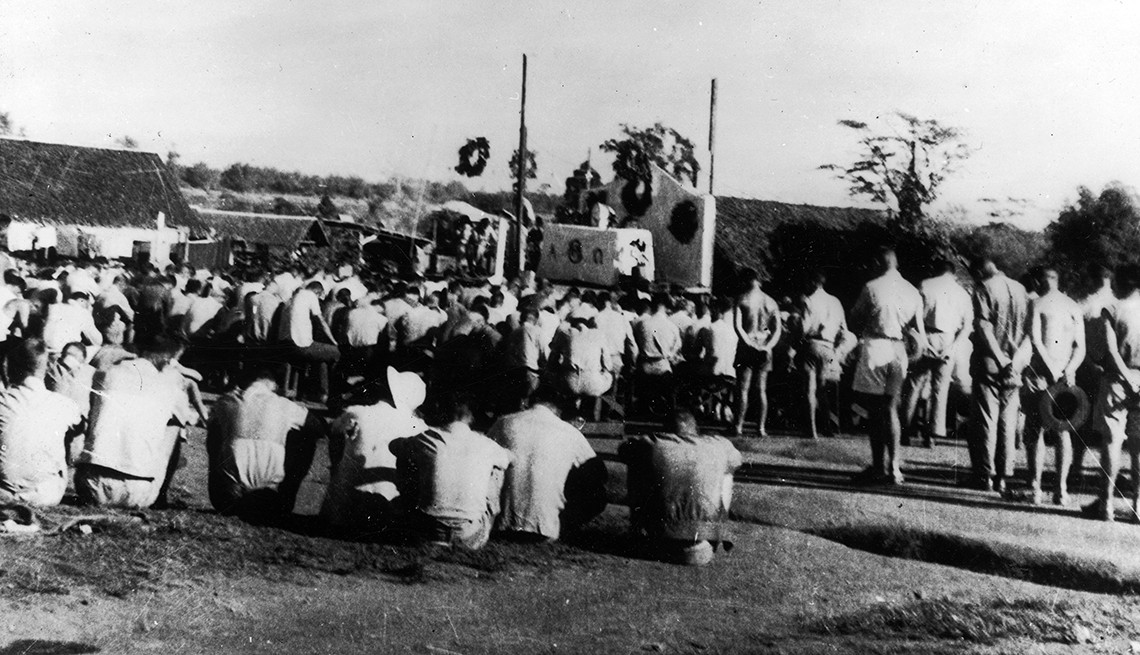

December 15, 1942, was a special day for the starving prisoners at Cabanatuan camp in the Philippines. “The first day in prison without a single death,” reported Calvin Ellsworth Chunn, a Marine captain captured during the Japanese invasion that year. “A reprieve granted solely by nourishment.”

The reason for the abrupt change in conditions was a decision by the Japanese camp authorities to allow Red Cross packages — containing tobacco, hygiene items, and most importantly food — to be distributed among the prisoners.

It was a rare departure from the endless, monotonous brutality meted out on the prison population throughout the Philippine archipelago. And it was because of Christmas.

“No children anticipating Christmas, when they could actually gain possession of countless long-wished-for articles, ever suffered any more than we did while we were waiting for the distribution of our packages,” wrote Col. Irvin Alexander, also a prisoner.

For a few hours during Christmas of that year, however, some prisoners were allowed an opportunity to think back on the lives they had left behind, and their loved ones whom they might never see again.

Make no mistake: In many Japanese camps, probably most, the treatment in December 1942 was as horrific as at any other time of the year. The Japanese prison camp experience was uniquely gruesome as far as the Western Allies were concerned.

The statistics bear this out. According to figures from the Department of Veterans Affairs, just over one percent of U.S. Army personnel taken prisoner by the Germans during World War II died while in captivity. Among members of the U.S. Army in Japanese camps, 40 percent did not make it home after the war.

Still, in a few POW camps in late December 1942, the Japanese relented, apparently out of respect for the Christian holiday, despite their well-known disdain for enemies who had allowed themselves to be taken alive.

At a camp in Japanese-occupied Formosa, now Taiwan, ranking Allied officers spent time decorating their barracks with what little means they could find. Some organized Christmas entertainment in the form of a choir singing traditional carols.

More From AARP

Gary Sinise Salutes America’s Pearl Harbor Heroes

Only a handful of survivors of that day of infamy are still with usWounded in Korea, Praised by MacArthur and Still Going Strong

Back in 1950, serving in a segregated unit was ‘just status quo’10 Holiday Shopping Tips to Get the Most from Veteran Discounts

The deals are out there, but you need to be smart to land the best onesHe Lost a Leg in Combat, But It Only Spurred Him On

Brad Halling paved the way for other amputees to keep serving in the U.S. militaryRecommended for You