AARP Hearing Center

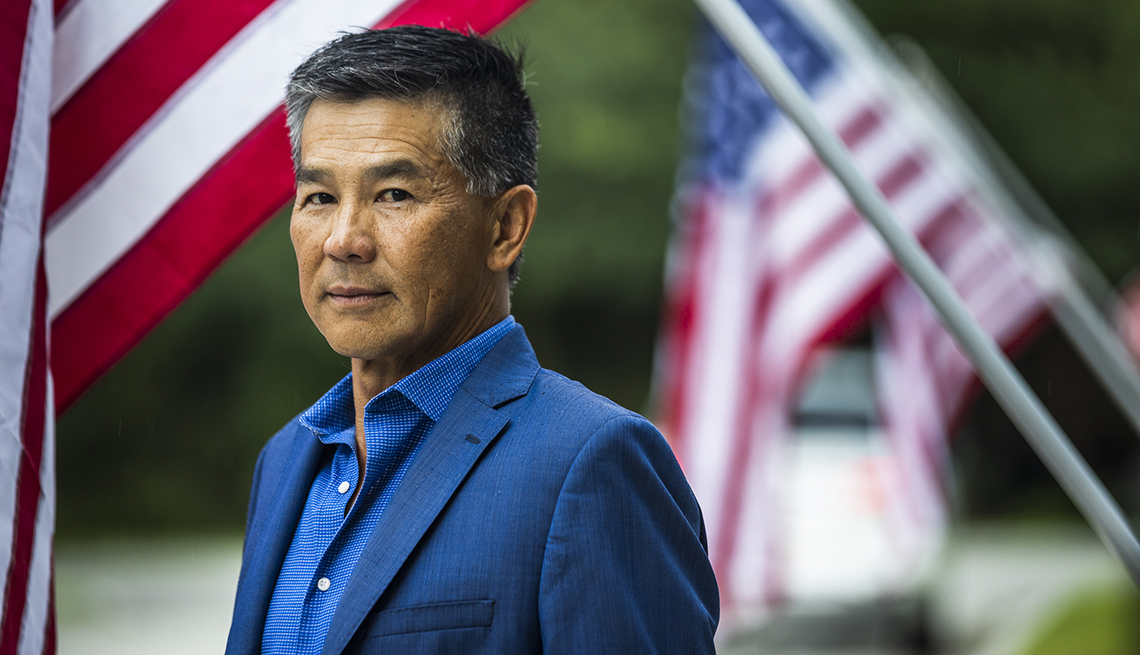

I was born in Saigon about six months before the United States ordered combat troops into the war in March 1965. My father was a lieutenant colonel in the South Vietnamese Air Force. When Saigon fell in 1975 and the North Vietnamese overran the whole area, I had just finished the fifth grade. Evacuations started in secrecy because they didn’t want the whole country to panic.

You can subscribe here to AARP Veteran Report, a free e-newsletter published every two weeks. If you have feedback or a story idea then please contact us here.

The planes started flying out at 2 a.m. on April 22. We were on the second flight — me, my three sisters and my mother. I remember big, tall Americans helping us onto the C-130, and I can still hear in my mind the sound of the thundering engines. My father remained behind and became a military prisoner. For many years, we never knew if he was alive or dead.

My family ended up in Oxnard, California. When we moved there, people would say, “What are you doing here? I thought you were the enemy.” I said, “No, we’re on the American side. We lost the war.”

My father was my hero, and I had dreams of becoming a military pilot like him. But those dreams vanished. I went to UCLA to study business. Then one day, I saw a Marine captain on campus, a recruiter in his dress blues. He saw me looking at a brochure and said, “How would you like to go to officer candidate school?”

I had just become an American citizen, but I had never seen an Asian American in the U.S. military. I ended up getting my degree, and when I showed up at officer candidate school in 1986, in Quantico, Virginia, my father was still in prison.

The biggest shock was how much the Vietnam War was still on the minds of the U.S. military. I got the crap beat out of me, mentally. There were a lot of racial slurs. But there was no way I was not going to make it through.

When I became an officer, things changed. I went through flight school, did well, and when I got to my squadron in 1990, the Gulf War kicked off. I was a new copilot aboard a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter, and I volunteered to go. When I showed up in Saudi Arabia, I was the second youngest pilot, as far as experience goes, in my squadron.

We flew medevac, and I was part of a two-helicopter team. We flew the first medical evacuation out of Kuwait International Airport, on Feb. 27, 1991. I flew through smoky fields at 120 knots, 50 feet off the desert floor. We got Marines evacuated and we flew out some Iraqi prisoners.

As I was getting ready for my second deployment, my father finally arrived in America. The last time I had seen him, he was wearing a flight suit, in Saigon. Seventeen and a half years later, in November 1992, after serving 12 years in prison, here he was at the Marine Corps Station in Tustin, California, a free man. I was a Marine pilot. We were united, and my life had come full circle.