AARP Hearing Center

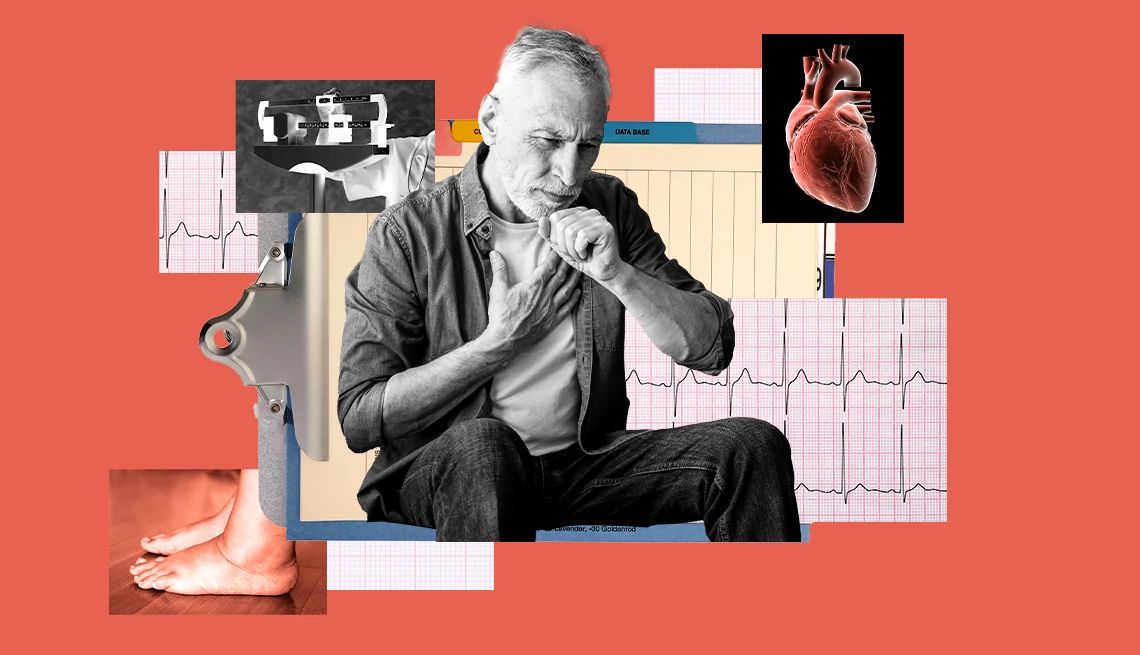

Bill Miller felt like he had been kicked in the chest by a horse.

When Miller’s internal defibrillator detected an irregular heartbeat — the kind that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest — it sent a series of powerful shocks to jump-start his heart. Because Miller’s heart was severely out of rhythm — the cardiac equivalent of an electrical storm — the device fired 22 times.

The first shock knocked Miller out of his chair at a restaurant. The pain was so intense that Miller, then 56, began screaming for someone to turn the defibrillator off. In spite of the pain it caused, Miller, 62, says, “the defibrillator saved my life.… It was a wake-up call.”

Miller had been diagnosed with heart failure three years before his near-death experience. Heart failure is a serious condition in which the heart muscle becomes too weak to pump blood to the rest of the body, which can deprive vital organs and tissues of oxygen.

And while Miller took the medication his doctors prescribed, he says he didn’t pay enough attention to his doctors’ warnings and continued working long hours at a stressful job in banking.

Deaths from heart failure are on the rise

One in four Americans develop heart failure, which contributes to the deaths of about 425,000 people in the U.S. each year. It’s estimated that 6.7 million people are living with heart failure.

Deaths from heart attacks have fallen sharply in recent decades, thanks to medical innovations and lower smoking rates, according to a study published in June in the Journal of the American Heart Association. But up to 40 percent of Americans who survive heart attacks develop heart failure, which has contributed to the 146 percent increase in heart failure mortality from 1970 to 2022.

When Miller was first diagnosed with heart failure, the only warning signs were a cough that refused to go away, as well as fatigue, which Miller attributed to chronic sleep apnea. When he finally saw a cardiologist, tests showed Miller’s heart was pumping out only a fraction of the blood his body needed.

After a few months on medication, Miller’s doctor told him that he remained at very high risk of a heart attack and suggested the implantable defibrillator. After a while, Miller says, he almost forgot about the device in his chest.

“To be perfectly honest,” says Miller, of Pearl River, New York, “I was not taking it seriously enough.… You’ve got to pay attention to your doctors and pay attention to your health and what you’re eating, and I didn’t.”

Miller’s brush with death terrified him, he says. The experience left him with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as a determination to lead a healthier life.

“I got into the best physical condition of my life over the next 18 months,” says Miller, who received treatment for PTSD. He weighed 283 pounds when his heart stopped, after which he joined a weight-loss program and lost 87 pounds. He says he realized he had no choice but to change his habits.

More From AARP

Can Hypertension Cause Dementia? What to Know

High blood pressure in midlife may increase risk of dementia

Lowering Blood Pressure Has Brain Benefits

New guidelines highlight the importance of managing hypertension

Heart-Smart Choices for a Healthier Day

Heart-healthy habits for every part of your day