AARP Hearing Center

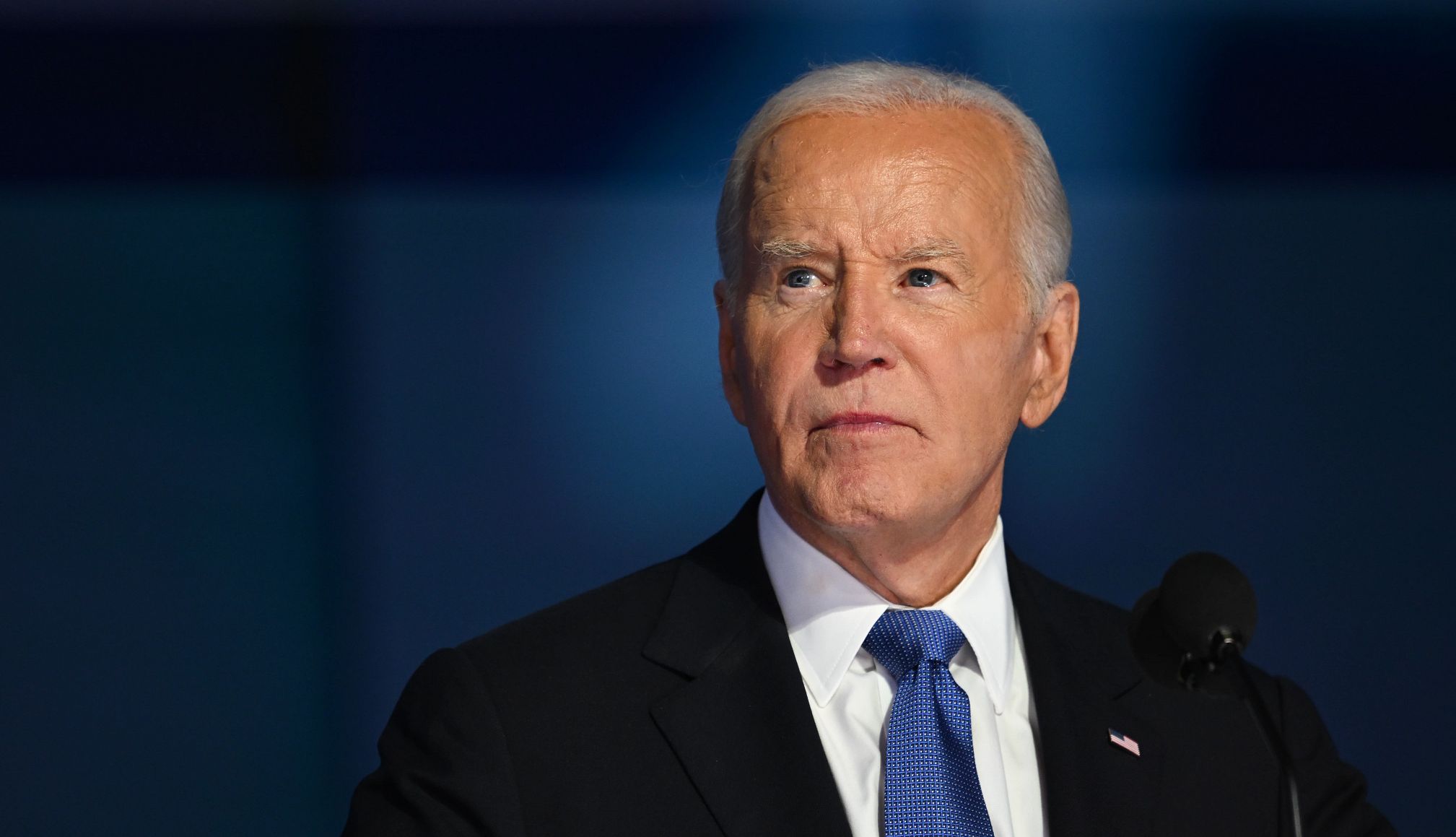

In his first public remarks since announcing his prostate cancer diagnosis, former President Joe Biden told reporters at a veterans memorial event in Delaware that he is feeling “optimistic” about his prognosis and has started treatment, which according to CNN, involves a daily pill for six weeks.

“The expectation is we’re going to be able to beat this,” said Biden, who mentioned he’s also working with a leading surgeon. “My bones are strong. It hasn’t penetrated, so I’m feeling good.”

On May 19, Biden’s office announced that the 46th president had been diagnosed with an aggressive form of prostate cancer that has spread to his bones. After he experienced urinary symptoms, doctors discovered a nodule on his prostate that led them to investigate.

“While this represents a more aggressive form of the disease, the cancer appears to be hormone-sensitive, which allows for effective management,” his office said in a statement.

Biden’s cancer is characterized by a Gleason score of 9, according to his office, which suggests his cancer is aggressive. Gleason scores are a grading system for prostate cancer and can range from 6 (low-grade cancer) to 10 (high-grade cancer). When cancer metastasizes to the bones, it can be harder to treat. However, because Biden’s prostate cancer needs hormones to grow, a treatment that deprives the tumor of hormones can be effective. But cancer doctors say that although Biden’s form of cancer is treatable, it’s likely not curable.

Here’s a look at some of the symptoms men with prostate cancer may experience — and how doctors diagnose and treat the disease.

5 Warning Signs

A few symptoms point to prostate problems, both benign and cancerous. To be safe, inform your doctor if you have any of the following issues:

- Peeing problems. A weak stream, trouble getting the flow started or an urgent need to go (especially at night) are signs that your prostate is enlarged from BPH or cancer.

- Blood in your urine. This symptom could indicate a urinary tract infection, but it’s one worth getting checked out.

- Pain or discomfort when you pee or sit may also be due to an infection, but see your doctor to make sure. Pain in your back, chest or hips is a sign of more advanced cancer that has spread to the bones.

- Erectile dysfunction. Although this problem plagues some men naturally as they age, prostate cancer also can interfere with your ability to get an erection.

- Painful ejaculation. Less semen than usual during ejaculation and blood in your semen are other prostate cancer warning signs.

Understanding prostate cancer

If you’re a man of a certain age, your mind may immediately veer to the worst possible scenario for your symptoms: prostate cancer. But while cancer can cause urinary problems, it’s far from the most likely reason.

“The vast majority of men with those symptoms don’t have prostate cancer,” explains Todd Morgan, M.D., chief of Urologic Oncology at Michigan Medicine. “They’re usually symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH.” This is a noncancerous enlargement of the prostate.