AARP Hearing Center

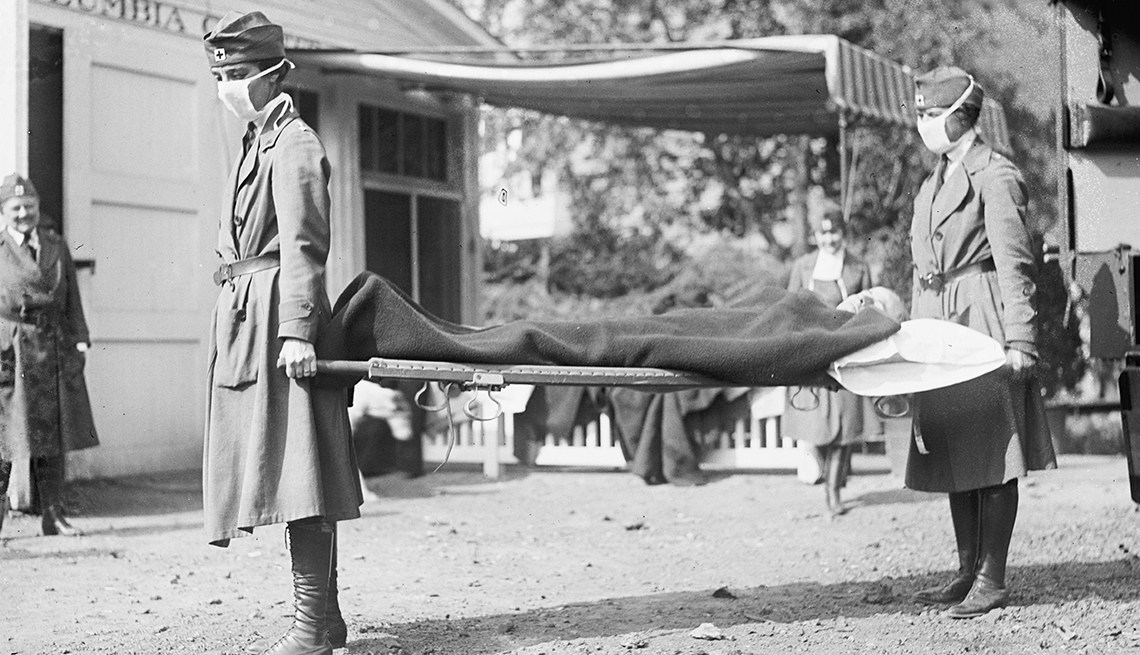

Though they occurred more than 100 years apart, the 1918 influenza pandemic and the current COVID-19 pandemic share similarities. Both were caused by viruses that can trigger respiratory illness; both spread by respiratory droplets and aerosols; both prompted public safety efforts like face masks, social distancing and shutdowns; and both resulted in hundreds of thousands of U.S. deaths (and millions worldwide) that played out over a series of surges.

An estimated 675,000 Americans died from the flu of 1918, also known as the Spanish flu, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); COVID-19 has so far taken more than 915,000 U.S. lives.

It’s no surprise, then, that many people are turning to the history books to see if this past pandemic can shed any light on when we might finally be on the COVID-19 exit ramp — especially now that new cases caused by the highly contagious omicron variant, while still high, are plummeting in many areas of the country.

But experts urge caution in comparing the two pandemics. There are commonalities, but “they are different viruses,” says John M. Barry, distinguished scholar at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and author of The Great Influenza.

“We can use [the 1918 flu pandemic] as a guidepost in some ways, but we can't really overlay them with each other,” adds Egon Ozer, M.D., an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and director of the Center for Pathogen Genomics and Microbial Evolution at the Havey Institute for Global Health. “What happened in that pandemic, we can't necessarily take as a given in this one.”

From pandemic to endemic

After a few fatal years, the virus that caused the 1918 pandemic eventually petered out. As population immunity from infection rose, deaths declined and the virus became a less lethal seasonal influenza — though descendants of it still circulate today, according to the CDC.

A growing number of scientists, including almost 90 percent of immunologists, infectious disease researchers and virologists polled by Nature, predict SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) will follow a somewhat similar path, in that it, too, could become endemic.

“Speaking very generally, what [endemic] means is that we, as a population, have a truce with the virus,” says infectious disease expert William Schaffner, M.D., a professor at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “The virus is reduced in its impact so that it doesn't disappear from our population — it's not totally gone. But you can think of it as smoldering. It continues to be transmitted at very low levels,” occasionally causing serious illness in vulnerable populations.

Hospitalizations and deaths are “substantially” reduced in an endemic stage, Schaffner explains, but they still occur. The seasonal flu, which is considered endemic, caused 12,000 to 52,000 deaths annually between 2010 and 2020, according to the CDC. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), another endemic virus, kills about 14,000 adults 65 and older every year, federal data shows.

Increased immunity, either by vaccination or natural infection, is what experts say will help to push us into this endemic state with COVID-19. After the end of the omicron wave, only a small sliver of the global population will be what scientists call “immunologically naive,” meaning that their immune systems will not have been introduced to the virus, according to Christopher Murray, M.D., director of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.