Staying Fit

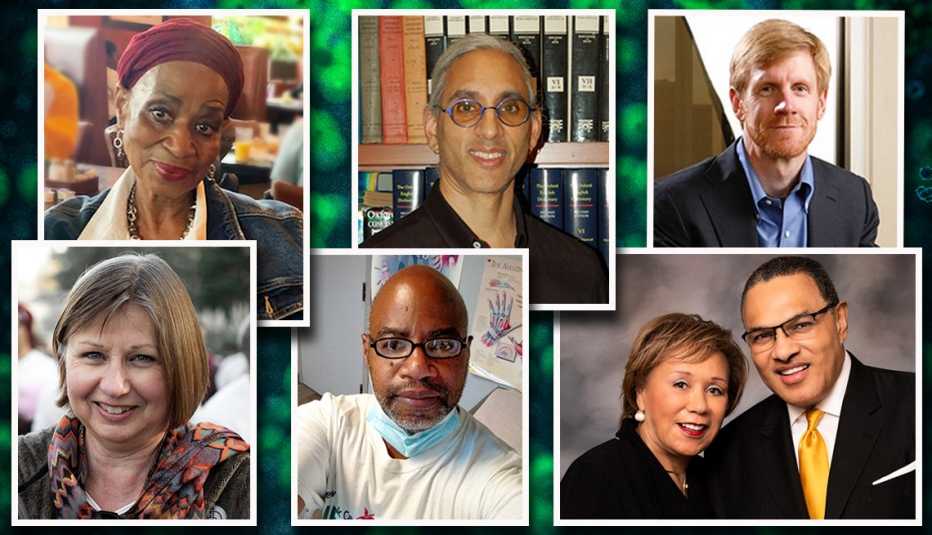

As researchers race to develop vaccines to combat the spread of the coronavirus, thousands of people around the country have been offering their bodies to science. These health heroes have volunteered to be participants in clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines that are currently in development. Because these are blind studies, the participants don't know whether they are getting the real vaccine or a placebo. These volunteers come from various walks of life and express a variety of reasons for becoming involved. Common to all, however, is a desire to put an end to this pandemic.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

What follows is a series of snapshots of people over age 50 who are participating in these trials and what their personal motivation is for doing so. Their inspiring stories, told in their own words, have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

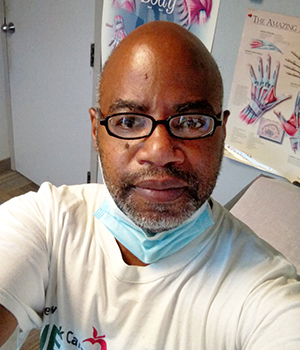

Bonnie Blue, 68, is an author, mother of four, and a great-grandmother in Chicago.

Because of severe asthma, I'd been fighting to exist my whole life. I'd been in and out of hospitals, ICUs, and on life support 13 times. I wouldn't want anyone else to go through what I've gone through — if I can help people avoid that, I want to do my part.

Like most African Americans, I wasn't very trusting of the medical community. My friends and I discussed waiting a few years to see if the vaccine was safe or not. But I saw that the numbers of infections and deaths kept going up, and for every death I know there's a family that loved that person. It breaks my heart when I hear about people not being able to be with their COVID-stricken loved ones as they're dying and to see children being orphaned from this.

So I started doing research and heard about the clinical trial at the University of Illinois at Chicago. I had not volunteered for a clinical trial before and my loved ones tried to talk me out of it. I'm a praying woman and I asked for a sign of whether or not I should volunteer for this. I didn't get a sign that I shouldn't do it so I signed up. I got the first injection in late August and the second in late September.

I wanted to do my part for humanity because this microorganism we can't see is destroying mankind. This is the point in history where we can come together to help each other survive; we're in this together. This is just my small contribution so that we can all live and be well.

Deepak Sarma, 51, is a professor of religious studies and bioethics at Case Western University in Cleveland and a father of two.

My wife is a primary care physician, and I had seen her worrying about the virus. When I heard about the opportunity to enroll in a phase III clinical trial, I thought, Wow! I can do something. I'm a healthy South-Asian American — my parents are from India — and I don't have any preexisting conditions. Not only did enrolling in the study satisfy my altruistic goals, but it also coincides with my Hindu beliefs.

More From AARP

What to Know About the Coronavirus Vaccines

Questions continue as millions of Americans get immunized