AARP Hearing Center

More than 350,000 Americans die each year from sudden cardiac arrest outside of hospitals, but many of them could be saved if you know how to use a defibrillator.

An automated external defibrillator (AED) is used if someone goes into cardiac arrest. That occurs when the heart stops pumping and the brain doesn’t get oxygen from blood. During a cardiac arrest, a person will be unresponsive, not breathing at all or gasping for air.

“If somebody has a cardiac arrest, it’s not subtle. They are on the ground, and they are not responding to you,” says Dr. Gregory Katz, a cardiologist at NYU Langone and an assistant professor in the department of medicine at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

AED Laws

Most jurisdictions have some type of legal protection to prevent lawsuits under Good Samaritan statutes if you use an AED and the recipient dies or has other complications from AED use, according to the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation.

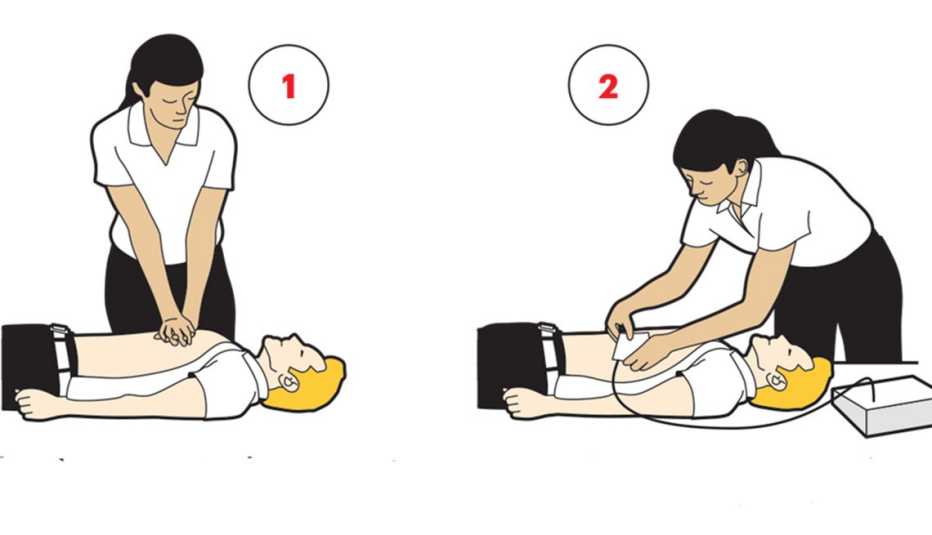

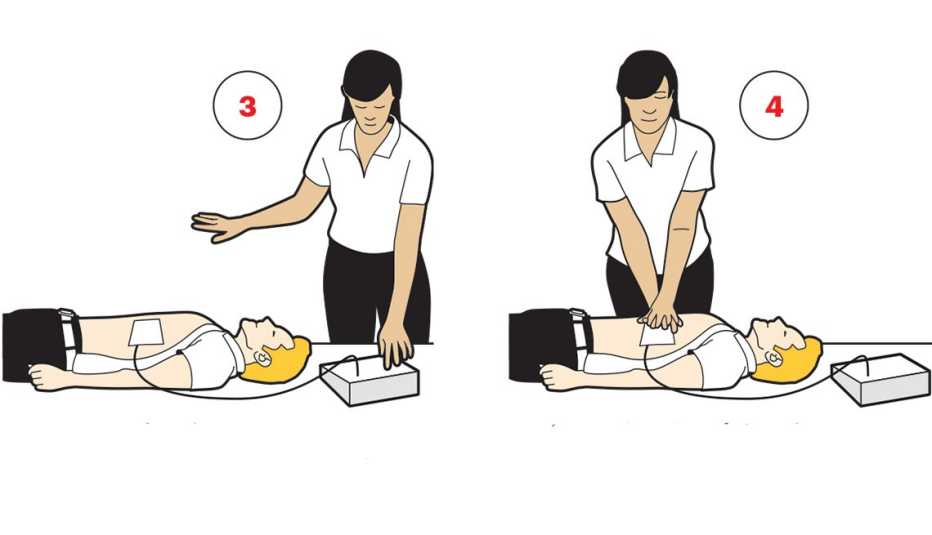

In the event of a cardiac arrest, you can use cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if you don’t have an AED, but the odds of survival increase if you use both.

A 2024 report in Resuscitation Plus found that nearly 85 percent of cardiac arrests happen at home. Bystanders — those without formal medical training — gave CPR in 42 percent of cases, but AEDs largely were not used. About one-quarter of at-home cardiac arrests happened within a four-minute walk of an AED, the data shows.

What is an AED?

There are two kinds of AEDs: A semiautomatic AED is applied to the person’s bare, dry chest and determines whether the person needs to be shocked. The user must push a button to start the shock. A fully automatic AED delivers a shock without the press of a button to restore the natural rhythm if needed.

AEDs are available in many public places, such as government buildings and schools, as well as in fitness centers, large apartment buildings and medical offices. The devices are stored in wall cabinets, similar to fire extinguishers.

When an AED is used promptly, the chances of survival increase. Nine in 10 people who experience cardiac arrest and receive a shock from an AED in the first minute survive, the American Heart Association reports.

Is AED training necessary?

No. The devices are intended to be used by those with minimal training, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration says.

Often, people who see someone in need won’t use an AED because they don’t think they can operate it. That’s an unfounded fear, according to Clifton Callaway, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and associate director of cardiopulmonary arrest research at the Safar Center for Resuscitation Research. The device is automatic, he says, and “a 911 operator can talk you through it.”

A 2025 report in Internal Medicine evaluated ease of use and preferences in AED use among health care professionals and those without training. They looked at semiautomatic and automatic AED use among 47 medical professionals and 396 nonprofessionals. Preferences vary among those groups, as there’s some reluctance toward the semiautomatic devices, while fully automatic devices may ease hesitation.

Find an AED

The PulsePoint Foundation has an app that allows emergency personnel and citizens to quickly locate the nearest AED. The free app also enables the community to report AED locations to build a larger device registry.

More From AARP

8 Things to Know About Heart Disease

Heart disease risks and prevention tips for people 50-plusKnowing Your Cardiovascular Risks

Over 99% of people that suffered a heart event had a non-optimal risk factor.

AARP Smart Guide to a Healthy Heart

Easy, expert-endorsed ideas to help you care for your heart