AARP Hearing Center

More than 20 years ago, my sister and I went looking for our great-grandmother's grave. We never found it, but the search awakened a calling in me that has driven me ever since.

We'd traveled to Texas for a family reunion, and while there, we went to the cemetery listed on my great-grandmother's death certificate. The main graveyard was bright and pristine, and we soon realized we were in the section historically set aside for white people. The section for African Americans was in the nearby woods, where we found graves in the shadows, under downed trees. It was surreal.

We located some family, if not the grave we were looking for. I felt incredibly proud that my family had endured slavery and segregation and survived long enough for me to be here. And it got me thinking: What else didn't I know?

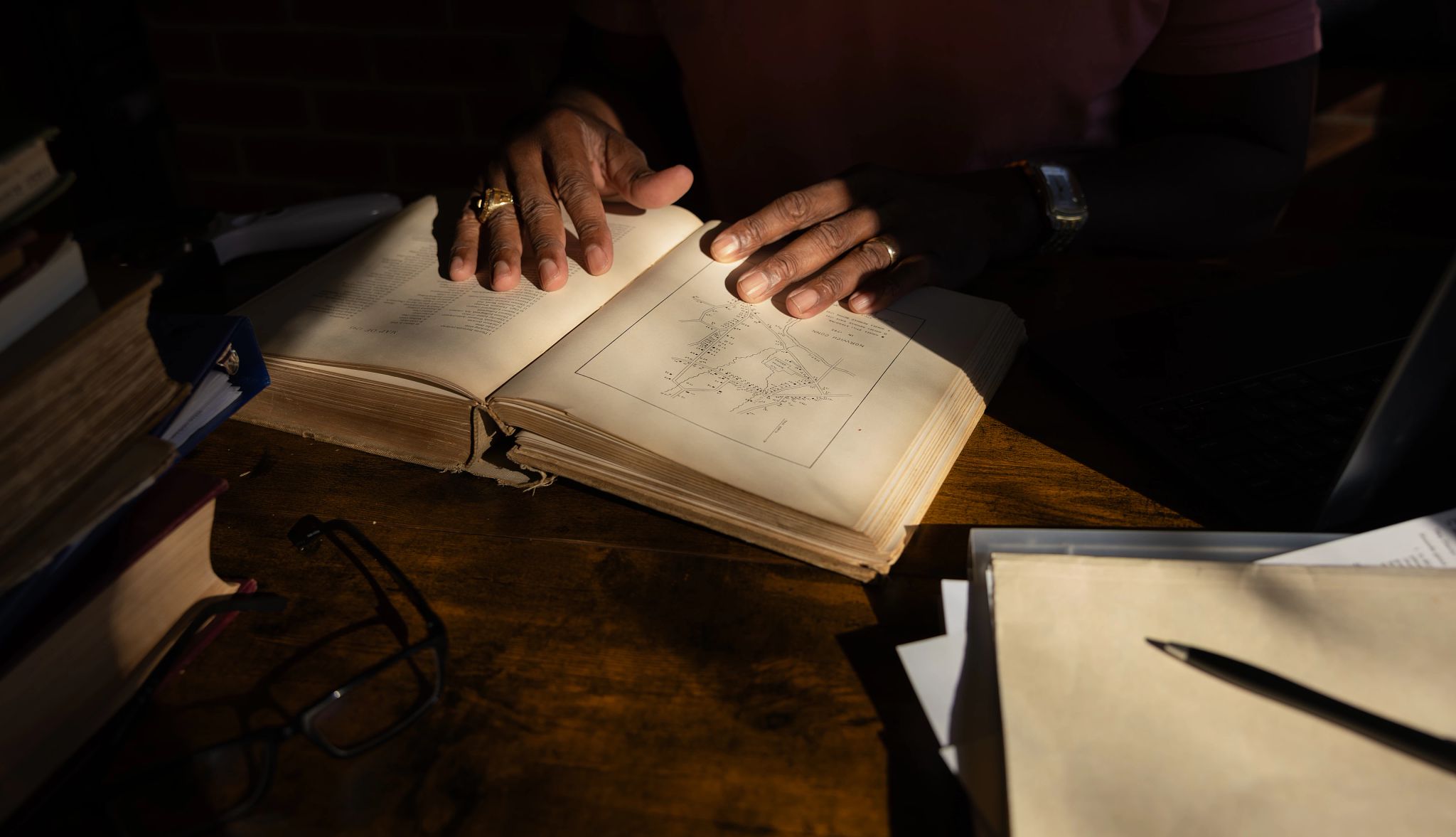

I dug into genealogical research. My forebears weren't exceptional; they weren't the Harriet Tubmans. Still, knowing about their lives made me stand up straighter. But many African Americans don't have access to their ancestry. So I started researching ordinary African Americans from the past—people I’d read about in newspaper articles or obituaries. I also bought old pension records and birth, death and marriage certificates. I would write brief biographies and post them on social media, and people started following.

Going backwards in time is a difficult process because the people I’m looking for tend to have been enslaved. Since they were considered property, they're not in census documents and probably don't have burial stones. In 2022, I started a nonprofit to find and tell these lost stories. I also began researching forward in time, so that I could connect living descendants with the stories of their ancestors.

People feel a lot of legitimate pride in extraordinary people like Martin Luther King Jr., who make a place for themselves in American history. The one in a million. But I believe we can and should also feel pride in the other 999,999. The ones whose everyday strength led us here.

How to Research an Enslaved Ancestor

Documentation can be scarce. Mills shares three tips:

Talk to knowledgeable elders. Record their oral histories via audio or video. Passed-down stories contain valuable clues that can help direct further research.

Visit your state library. These tend to have professional genealogists on staff who can assist with research.

Consider hiring a pro. The directory at the Board for Certification of Genealogists website (bcgcertification.org) lets you search by area of specialty.

— L.Q.W.

How to Research an Enslaved Ancestor

Documentation can be scarce. Mills shares three tips:

Talk to knowledgeable elders. Record their oral histories via audio or video. Passed-down stories contain valuable clues that can help direct further research.

Visit your state library. These tend to have professional genealogists on staff who can assist with research.

Consider hiring a pro. The directory at the Board for Certification of Genealogists website (bcgcertification.org) lets you search by area of specialty.

— L.Q.W.

You Might Also Like

'Finding Your Roots' Host Shares Celebs' Family Secrets (and How He Made Sharon Stone Cry)

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. gives AARP a sneak preview of his ancestry show's 2025 season

25 Great Ways to Step Outside Your Comfort Zone

Push past complacency by trying things you’ve never done beforeHow Wayne Wong Helped Invent an Olympic Sport

More than 50 years after freestyle skiing began, he continues to refine it