AARP Hearing Center

It’s that time again to write Michael Collins a check to mow and weed my father’s grave. I pay him $250 a year.

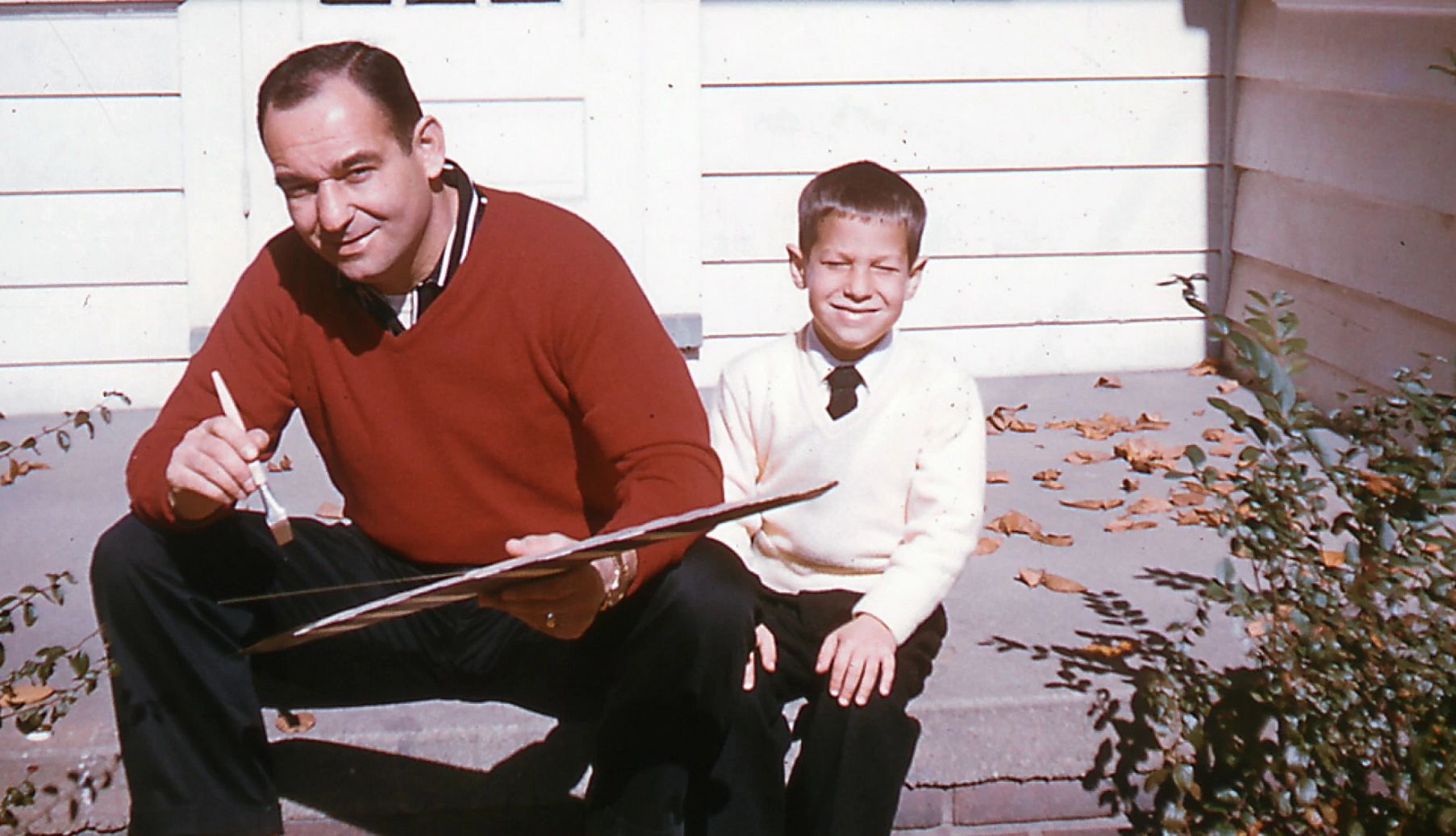

My father was felled by a heart attack 51 years ago. He was 50; I was 23. It still gives me something of a start to climb that hill in Canton, Ohio’s West Lawn Cemetery and come upon his grave. To see his name — my name, Theodore Gup — etched into the granite, reminds me of that scene in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol when Scrooge stands before his own grave. A wave of regrets washes over him, and he resolves to mend his selfish ways. Only in fiction is such a redo possible; real life offers few mulligans.

I am now 74 and rounding the final turn myself. Death, once so remote and abstract, is now neither.

Early on, I knew that our family’s Jewish tradition forbade a child from being named after a living parent. I was told it was out of fear that the Angel of Death would take the child out of turn. My father’s defiance tempted fate.

I am no more religious than my father was. Still, my wife and I did not name our firstborn Theodore. Instead, we called him David. It means “beloved,” and beloved he surely was. But at 21, David was snatched away by a drug overdose, and I was condemned to carry on. I lived that cliché — “No parent should have to bury a child” — and for years, I knew that was how others saw me: the bereft and broken father, the embodiment of unspoken fears.

In all things, David colored outside the lines. For that, others were drawn to him as to a magnet. And he was smart. He could barely pass his own exams, but at the end of each semester, signing in as one friend or another, he would take their exams for them and ace them. Among the papers found at the foot of his bed, I came across an interview between David and a friend of mine, a best-selling author. It vividly captured her personality and made me proud. There was so much promise there. Years later, I discovered he had never spoken with her.

You Might Also Like

What Could Cause Sudden, Severe Memory Loss?

Causes and signs of transient global amnesia

How Can I Calm Anxiety?

A doctor's advice on dealing with tension and worry

What I Learned on My Europe Adventure With My Nephew

Being flexible, compromising and ceding control enhanced our experiences