AARP Hearing Center

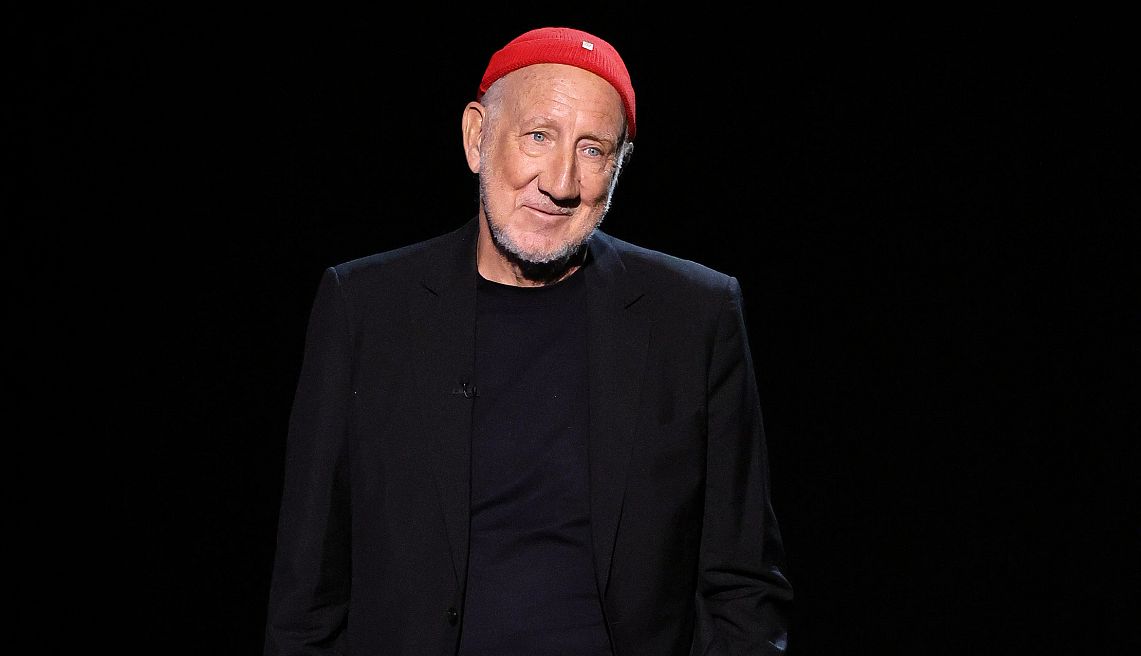

Pete Townshend, The Who’s guitarist and main songwriter, wrote “My Generation” in 1965 at 20, penning the iconic line: “I hope I die before I get old.” Didn’t turn out that way. Townshend is 80, singer Roger Daltrey is 81. The Who’s drummer Keith Moon did die young at 32 in 1978, and bassist John Entwistle at 57 in 2002.

But Townshend and Daltrey are on what they promise is (really this time!) the final Who tour, “The Song Is Over,” a 17-date trek across North America (Aug. 16 to Sept. 28). Scott Devours, 58, takes the spot of Ringo Starr’s son Zak Starkey, 59, their recently sacked longtime drummer; the bassist since 2017 has been Jon Button, 54.

“We reserve the right to pop up again,” says Townshend wryly, by phone from his London home, “but I think one thing is very clear: that at our age, we will not.” He has no intention of retiring, however, and he’s got an album, The Age of Anxiety, he’s been working on since 2007. He’ll likely continue to write for Daltrey. Townshend gave AARP his thoughts about his tumultuous past, present and future plans.

You’ve often said you don’t like touring — why do it one last time?

It can be lonely. I’ve thought, Well, this is my job, I’m happy to have the work, but I prefer to be doing something else. Then, I think, Well, I’m 80 years old. Why shouldn’t I revel in it? Why shouldn’t I celebrate?

Why keep The Who going after Keith Moon and John Entwistle died?

It’s a brand rather than a band. Roger and I have a duty to the music and the history. The Who [still] sells records —the Moon and Entwistle families have become millionaires. There’s also something more, really: the art, the creative work is when we perform it. We’re celebrating. We’re a Who tribute band.

But apart from that, it does whet an appetite to think about how we should bow out in our personal lives — what we do with our families and our friends and everything else at this age. We’re lucky to be alive. I’m looking forward to playing, Roger likes to throw wild cards out sometimes in the set, and we have learned and rehearsed a few songs that we don’t always play.

You and Daltrey have had a love/hate relationship. Do you feel on the same page now?

We don’t communicate very well. He and I are very different and we have different needs as performers. He got upset because he felt I had sometimes given the impression of having left the building. Roger complained about the fact that he is deaf. He’s a singer, and he has to be 100 percent fit in order to do his job.

More From AARP

More Rock Stars Are Facing Hearing Loss

How Dylan, Paul Simon and Dave Grohl are copingRock Icon Stevie Nicks Delays Tour After Injury

Stevie Nicks has postponed shows for the next two months after a shoulder injury

At 72, Cyndi Lauper Still Wants to Have Fun

The Grammy, Emmy and Tony winner is staying busy but is also ready to ‘smell the flowers’