Staying Fit

TV for Grownups

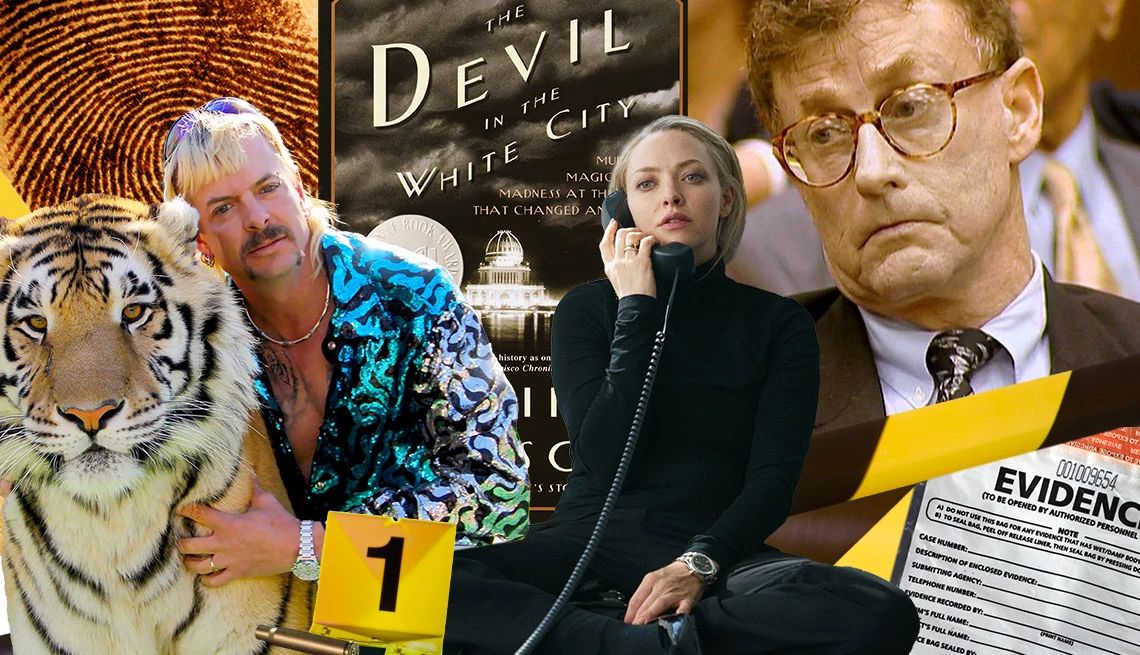

Discover the best TV shows, what’s new on Netflix and Amazon, and the best shows to stream right now

TV for Grownups News, Interviews and Top Lists

AARP Membership

$12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Videos

More on TV for Grownups

TV Technology