AARP Hearing Center

Oscar-winning actor Gene Hackman, wife Betsy Arakawa, and their dog were found dead in their New Mexico home on Feb. 26, the Santa Fe Sheriff’s office said. A subsequent investigation determined that the actor died of heart disease and showed severe signs of Alzheimer’s disease a full week after his wife died of hantavirus in their home.

Hackman, 95, was an unexpected star. His acting class voted him one of the least likely to succeed. He wasn’t movie-star handsome, and everything about him, from the way he carried his body to his Midwestern accent, gave him “the physical forgettability of that middle-management guy in the seat next to you on the flight from Rochester to Omaha,” as GQ magazine put it.

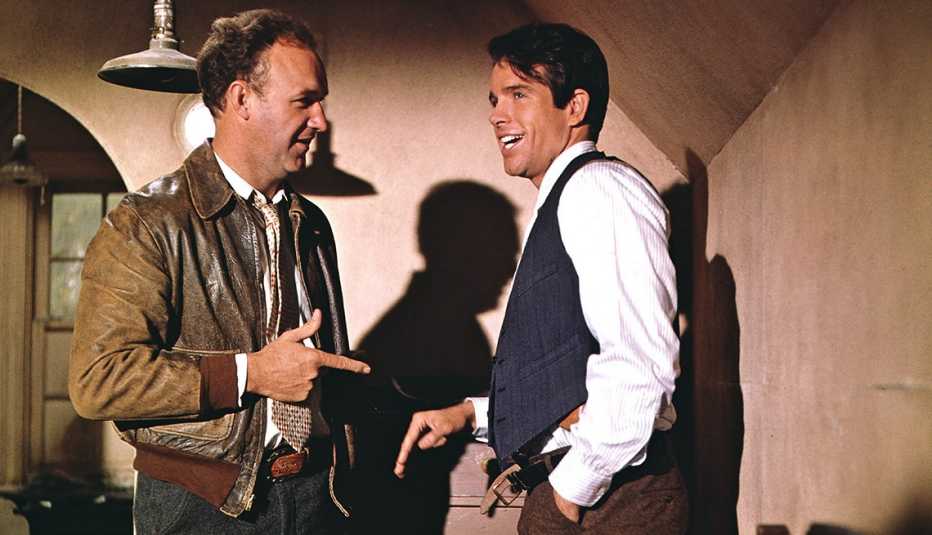

And yet his ability to embody the average schlub made Hackman one of the most recognizable and ubiquitous film actors in America, especially from the ’70s through the ’90s, portraying the furious drug cop Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and “Little” Bill Daggett in the Clint Eastwood western Unforgiven (1992). He won Academy Awards for both performances, and was nominated for Oscars for his performance as Clyde Barrow’s hapless brother, Buck, in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and for his roles in I Never Sang for My Father (1970) and Mississippi Burning (1988). His other significant films include Scarecrow (1973); Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), which Hackman called “the pinnacle of my acting career in terms of character development”; Superman (1978); Hoosiers (1986); No Way Out (1987); and Get Shorty (1995).

By 1989, with The Package, the then-58-year-old had made 50 films since 1961, and 19 in the previous eight years alone. As his fame and reputation grew, he became enormously well-paid, pulling in $100,000 for The French Connection but commanding $2 million for Superman in just seven years’ time. Still, he wasn’t comfortable with all that came with it: “I was trained to be an actor, not a star,” he once told the BBC. “I was trained to play roles, not to deal with fame and agents and lawyers and the press.”

Such sensitivity — and brooding — was necessary, he thought, to help him draw upon difficult personal moments for his roles.

“He will go back and visit some early pain that many of us would rather not touch,'' Arthur Penn, who directed him in Bonnie and Clyde, told The New York Times. “He's one of the ones who are willing to plunge their arm into the fire as far as it can go.”

Born in San Bernardino, California, on Jan. 30, 1930, Hackman was 13, living in Danville, Illinois, with his parents in the house of his maternal grandmother, when his father, a journeyman pressman who had moved the family to four states before settling in Illinois, abandoned them.

“I was playing down the street at a friend's house,” Hackman told The New York Times in 1989. “It was a Saturday, and my dad and I would do things on a Saturday, if he could. That day, he drove by and waved at me, and I knew from that wave that he wasn't coming back. It was very peculiar because there had been no troubles in the house, but somehow or another, I sensed from that wave it was over, and I ran home to ask my mom what was the matter. That wave, it was like he was saying, ‘OK, it's all yours. You're on your own, kiddo.’ ”

More From AARP

Grammy Award-Winning Singer-Songwriter Roberta Flack Dies at 88

The artist topped the charts with ‘Killing Me Softly with His Song’ and ‘The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face’

Peter Yarrow of Folk-Music Trio Peter, Paul and Mary Dies at 86

The Grammy-winning singer co-wrote ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ and was a passionate civil rights and war activist

Iconic New York Sports Broadcaster Al Trautwig Dies at 68

The longtime commentator for the MSG Networks also covered 16 Olympic games