AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Nineteen

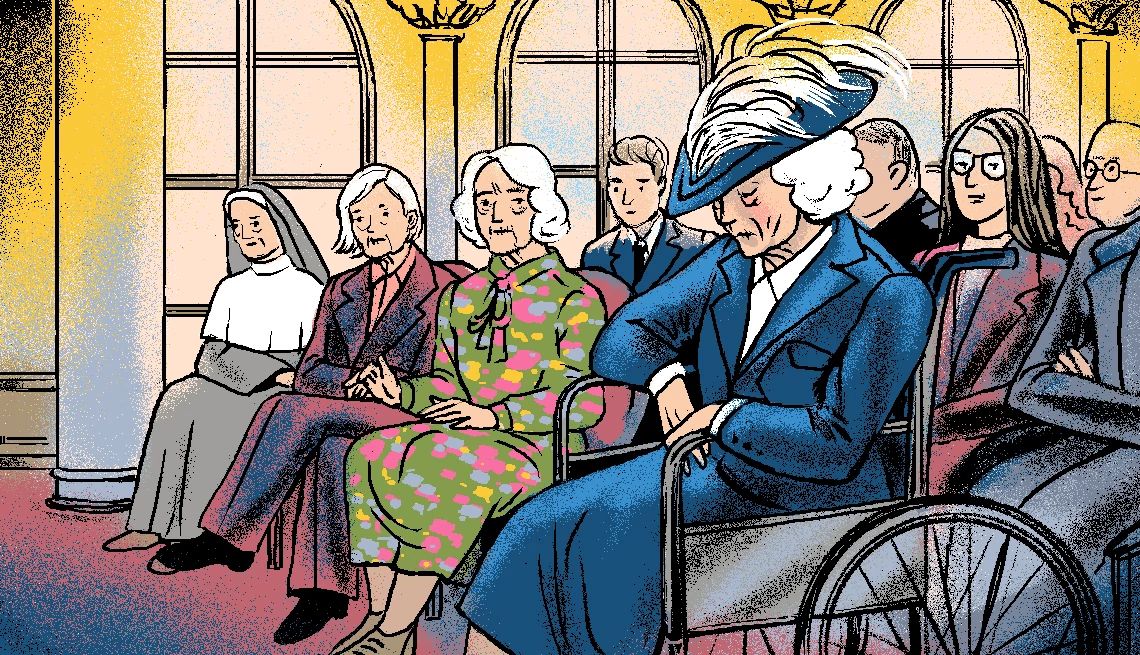

Forty-five minutes later, the functionary was still talking. Meanwhile, the sun had moved through the sky so that it was now shining directly into the room where the ceremony was being held, raising the temperature until even Archie was tempted to take off his jacket. Not that he ever would. He remained as immaculate as when he’d left The Maritime after breakfast, but he worried for Josephine and Penny, who were sitting in a shaft of bright sunlight. He wasn’t sure how they would get on if it started to get very much hotter.

As it was, the sisters were fine, if a little bored. Josephine glanced at Penny, who had her hands on her knees. No one would have thought it unusual for an old woman to be fidgeting from time to time—age brought with it all sorts of embarrassing tics and tremors—but of course Josephine knew that the movements of the fingers on her sister’s right hand were anything but random. “Dash dot dot pause dash dash dash ...”

Josephine tuned in. “Dot dot dash ...”

Penny was talking in Morse.

“Do U think speech go on longer? Need spend penny.”

Josephine responded, “Dash dot dash dash ... Shld have gone b4 ceremony started.”

As the man on the podium continued to praise the tenacity of the French Resistance, Penny tapped back, “Did. Bladder shot.” Then, “Dash dash pause dot dot ... Might wet self.”

To which Josephine replied, “U smell of pee anyway.”

“Dot dash dot dot ... Like Prinz Eugen.”

Josephine tried not to snigger. “Unkind,” she tapped back. “Ashamed to be sister.”

Penny grinned at that. “My work is done,” she whispered.

As the dignitary continued his interminable speech, oblivious to the discomfort of his audience, Josephine and Penny tapped out their private jokes, trying not to laugh out loud.

But what Josephine and Penny were forgetting was that they were not the only people in the room with impressive Morse code speeds honed in the theatre of war. Sister Eugenia had been one of the fastest coders in the Y Service and since those days when she tapped out messages all day long and often dreamt in code at night, she had not lost the ability to recognise a Morse pattern when she saw one. Thus she easily intercepted the sisters’ messages, just as they were tapping about wee.

At first Sister Eugenia couldn’t believe it. Prinz Eugen? Having established that they were not reminiscing about the battleship, Sister Eugenia realised it could only be her that the Williamson sisters were discussing. She felt a blush rush the full length of her body from her head to her toes (which usually felt very little).

“People who eavesdrop never hear good of themselves.”

She remembered the words of Sister Elizabeth, the first nun she ever met, back when she was a small girl at convent school in Sussex. Sister Elizabeth was fond of a morality tale and a clip round the ear to underline its message.

This is God’s punishment, Sister Eugenia told herself. I intercepted a signal that wasn’t meant for me and found out the Williamsons have nicknamed me after a battleship!

Perhaps it was a sign of affection, she tried to convince herself. It was just that Eugenia was easily shortened to Eugen, wasn’t it? And that she had been in the Y Service and actually taken down signals from that vessel? It wasn’t anything else ... It wasn’t anything about her girth? She knew gluttony was a sin, but really, when you were a ninety-eight-year-old nun, there was very little to keep one going through the long, long days. And during lockdown, the younger nuns had had such fun making cakes for the local community. It would have been churlish to refuse to taste their samples.

Sister Eugenia could hardly bear to think about it, yet her eyes were drawn back to Penny and Josephine’s hands, tap-tapping away.

Josephine coded, “Dash dash pause dot dash ... Mac’s hat. Monstrous.”

Just then Davina Mackenzie fell into a micro-snooze and her head dropped forward, leaving the feathers atop her tricorn all a-quiver.

“Dash dot pause dot ... Never wear thing telegraph movements,” Penny observed.

Sister Eugenia had to agree with that. Davina’s hat was rather ridiculous. And it did make it all the more obvious when Davina woke herself with a sudden snore that set her feathers trembling and the people in the row behind tittering.

Then at last—at long last—the honourees were called up to receive their medals. Josephine and Penny gave two short speeches in perfect French. Sister Eugenia shyly muttered, “Merci à Dieu et à la France.”

Davina Mackenzie seemed to speak for almost as long as the functionary, beginning her speech, naturally, “En tant que petite-fille d’un amiral ...”

Once all awards had been given out, the assembled crowd stood once again for “The Marseillaise.” Archie and the veterans all sang out with gusto.

ON THEIR WAY to the lunch reception afterwards, Archie and the sisters caught up with Sister Eugenia and Mrs. Mackenzie in the courtyard.

“Well, wasn’t that a lovely ceremony,” said Archie.

“If you ask me, it went on for much too long,” said Davina. “That man rather liked the sound of his own voice.”

“Oh I thought he gave a wonderful speech,” said Penny, just to be contrary. “Of course, I imagine it was much more interesting to those of us who speak fluent French.”

“It’s true I would have been much better able to grasp the nuances of his discourse had it been in German, Danish, or Norwegian,” Davina replied. “Well, you’ve got me there. My Norwegian is strictly conversational,” said Penny.

“I always get my Norwegian mixed up with my Swedish,” Josephine claimed.

“I wish I had your facility for languages, ladies,” Sister Eugenia sighed. “Apart from my schoolgirl German, the only other ‘language’—if you can call it that—that I’ve ever mastered is Morse. Still, that was all I needed when the Prinz Eugen was communicating in Enigma Code. You know I had a Morse speed of twenty-five words per minute, back in the day. I think I could still follow it at that speed though I’m not sure I could tap back so fast with my poor arthritic fingers.”

Penny and Josephine shared a worried look and Sister Eugenia felt an unchristian thrill at the thought that they knew they’d been rumbled.

IT WAS VERY warm in the courtyard that morning. While Penny and Josephine were still digesting Sister Eugenia’s Morse speed revelation, and Davina Mackenzie was expounding on the difficulty of procuring a decent cup of tea on “The Continent,” Davina’s carer suddenly swayed and fell to the floor like a sunflower chopped halfway down the stem.

Archie, Arlene, and Sister Eugenia’s young companion, Sister Margaret Ann, immediately went to the young woman’s aid. Archie took off his jacket—with a secret degree of relief to have an excuse—and made a pillow of it for her head.

“Too hot,” she murmured, as she came round from her faint.

“For goodness’ sake,” said Davina Mackenzie. “You simply cannot get the staff ... This is really most inconvenient.”

Arlene shot her former employer a poisonous look that would have finished off anyone else but it bounced off Davina Mackenzie like a rubber bullet off a Sherman tank.

It was decided that Hazel, as the unfortunate young woman was called, needed to have a lie down and a proper rest before she could return to her duties. She certainly couldn’t push Davina’s wheelchair all the way to the veterans’ lunch, which was taking place in a restaurant two streets away. Not far, but far enough.

“I’ll do it,” said Archie.

He gallantly stepped in. But though Archie was used to looking after ancient veterans, he was not used to pushing a wheelchair—it was hard even to persuade his great-aunts to use their sticks when they were out and about—and as he tried to move Davina Mackenzie’s chair out of the courtyard, he somehow got the small front wheels stuck in an invisible rut and very nearly deposited his demanding passenger face first in the gravel. Davina was unamused. She gave a blast on her bosun’s whistle and shouted, “This simply will not do!”

Flustered, Archie’s attempts to move the wheelchair only grew more panicky and less efficient, until Arlene could stand it no longer and said, “Get out of the way, Archie. I’m used to that old thing. I’ve got the biceps to prove it.”

It was true that Arlene had very impressive arms. Back in London, Arlene had seen off all-comers in the impromptu arm-wrestling contest Auntie Penny had arranged at the sisters’ last Christmas party. Archie couldn’t compete. He didn’t even try. His wrist had never truly recovered from when he broke it at ten years old.

“I’ll take Mrs. Mackenzie to the lunch and get her back to her hotel after- wards,” Arlene said now. “You keep an eye on the others.”

Archie gave Arlene a brief salute then they formed a convoy for journey to the restaurant, with former Third Officer Mackenzie (at the front, of course) occasionally blowing the “haul” on her boatswain’s whistle as “encouragement.”

The third time it happened, Penny blew an impressively loud raspberry in response and blamed it on her sister when Davina Mackenzie demanded, “Who was that?”

Chapter Twenty

The restaurant where the veterans were to have lunch had been chosen for its wartime links to the French Resistance. It had actually been a popular haunt with the occupying German troops. They’d had no idea that the friendly proprietor and his winsome young waitresses were eavesdropping on their conversations and passing on the information to a Resistance group that met in the restaurant’s wine cellar. The décor of the place had changed very little since the 1940s, one of the French hosts from the veterans’ association explained to the British guests, adding in a whisper, “Upstairs in the proprietor’s office, you can still see the bloodstains on the floor where a brave Resistance fighter slit the throat of a Gestapo officer she lured up there with the promise of sex.”

“Bloodstains.” Penny nodded enthusiastically. “We must see those.”

LUNCH WAS DELICIOUS, though Davina sent her food back three times before the meat was cooked to her satisfaction.

“Are they trying to kill us all off?” she asked loudly. “What happened to the Entente Cordiale?”

You’re dismantling it single-handedly, thought Archie.

Though Davina wasn’t one of Archie’s charges, strictly speaking, he felt an overwhelming need to apologise to the waiting staff on her behalf. She overheard him.

“What on earth are you apologising for, Archie?” she asked, in her foghorn voice. “They’ve had three opportunities to get my lunch right. Never say sorry for someone else ’s mistake.”

Archie wondered whether the waiter had wiped Davina’s steak across the kitchen floor on the third occasion of it being sent back. That was what the chef at the restaurant where he’d worked as a teenager would have done.

Thankfully, Penny and Josephine were being slightly less difficult than usual about the food though Archie began to worry when he noticed that somehow they had ended up with three wine glasses apiece by the time they finished the main course—champagne, white, and red. He should have kept a closer eye on them.

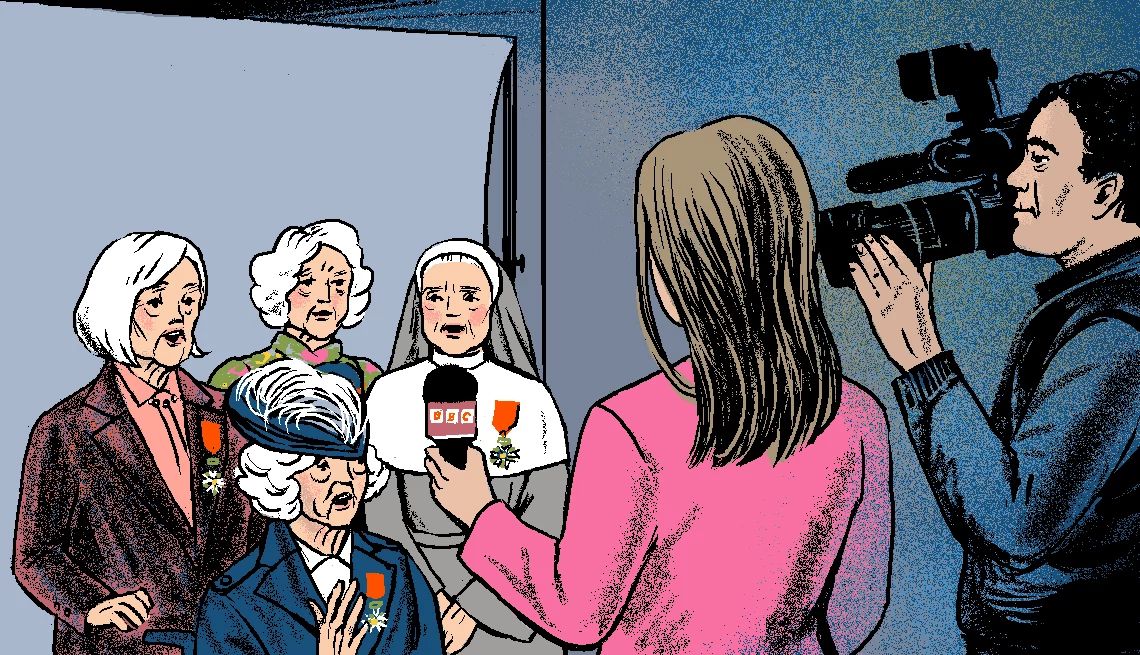

“Don’t forget the BBC interview at three!” he reminded them from across the table. Josephine raised a glass of burgundy to him to acknowledge the remark and in doing so spilled half its contents down the front of her dress.

Archie got up and swiftly removed the rest of his great-aunt’s wine stash, hissing, “If you get too merry, the BBC will have to interview Davina Mackenzie instead.”

“Well, I suppose she is the granddaughter of an admiral ...”

“What’s that about an admiral?” Davina shouted down the table. Her hearing aid batteries never wore out.

AS HE HELPED her blot the wine stain on her skirt, Archie noticed that Josephine’s new medal was already half hanging off its smart red ribbon.

“Let me pin that on again properly,” Archie suggested.

“It’s too heavy for this dress,” Josephine complained. “If I were wearing my navy suit, it wouldn’t keep drooping like this.”

“It is quite big,” Archie agreed, admiring the intricate medallion with its white five-pointed Napoleonic star interwoven with bright green enamelled laurel leaves. “The French certainly know how to do bling.”

“It’s less a medal than a hub-cap,” Sister Eugenia commented from the other side of the table as she admired her own new French decoration. “Or a shield. It rather overshadows my Bletchley brooch.”

“How did you get a Bletchley brooch?” Davina asked sharply.

“Well, we Y Service girls were the source of a good deal of Bletchley’s raw material ... If we hadn’t been listening in to the Kriegsmarine, they would have had nothing to decode.”

Meanwhile Penny was deep in conversation with a young man from the International Herald Tribune who was intending to cover the veterans’ inauguration and lunch for the paper’s weekend edition. Archie couldn’t help but tune in as the young man asked, “The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry were famously linked with the Special Operations Executive. Were you involved with any of that, Miss Williamson?”

“Well, I did work as a code and cipher officer for a while,” Penny confirmed. “But if you’re asking if I was an SOE agent ...”

Of course the journalist was asking that. Everyone always asked that. Archie asked it all the time. Hovering just behind Penny and her interlocutor, Archie wondered what sort of answer the journalist would get.

Chapter Twenty-One

Josephine’s retelling of her war years had always been quite straightforward. No matter how many times she recounted it, her story never really changed: basic training in London, a desk job at WRNS HQ, a stint in the Western Approaches plotting rooms in Plymouth, before finally returning to London to draw D-Day maps in a basement office in Whitehall. It was all very different with Penny.

In the course of researching the family history, Archie had already tracked down Josephine’s official war records, which confirmed exactly where and when she’d been posted during her four years with the Wrens. There were reports too, from her seniors. “A capable girl, if a little aloof when it comes to her fellow ratings,” wrote her commanding officer at WRNS HQ. Later, that aloofness would be to Josephine’s advantage in the eyes of the officers who put her forward for promotion from secretarial rating to young petty officer. “Not silly and given to gossip like some of the other girls.”

Archie had not been able to find anything like the same sort of information for Auntie Penny. It had taken a while to persuade the FANY archivists to look for the papers he wanted—he had to have Penny’s written permission and somehow she was always forgetting to give it—and when they finally did get back to him, the news was bad. They confirmed that Penny had indeed joined the FANY in 1942, shortly after her eighteenth birthday, but there was scant little information regarding Penny’s career between her basic training and her being posted first to Algiers in late 1943 and then to Southern Italy.

There was a gap in Penny’s records of more than a year and Archie found it maddening. Penny insisted she’d told him everything she could remember about those missing months—“Oh, I just had an admin job at an army training camp”—but he had hoped her official records might contain some tiny detail that would unlock a new and exciting anecdote. Where had those missing months gone?

A newly published book on the FANY, which Archie had downloaded onto his Kindle the very moment it was released, revealed that many of the FANY’s service records had been destroyed in a fire not long after the war. Archie had at first accepted that explanation but the more he thought about it, the more oddly convenient it seemed.

As the journalist talking to Penny had pointed out, it was now common knowledge that during World War Two the FANY had close links with the SOE—the Special Operations Executive. The covert wartime intelligence agency, commissioned by Churchill himself with the instruction that it should “Set Europe Ablaze,” was also known as the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare or the Baker Street Irregulars (its head office was on Baker Street). It was tasked with supporting resistance groups behind enemy lines in occupied Europe—often by sending in specially-trained agents. Its methods were subterfuge and sabotage. Its very existence was controversial.

Many FANY recruits were sent to work at the SOE in administrative and other support roles, but the FANY’s unique position as a voluntary organisation—a charity on the army list but not actually part of the army—meant that it was also perfectly placed to offer military status to the civilian women the SOE sent into the field as undercover agents, affording them the official protection due to military personnel under the 1929 Geneva Conventions, should they ever be captured.

A memorial on the wall of St. Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge commemorated the many FANY officers who had risked all as SOE agents behind enemy lines; women such as Violette Szabo and Odette Hallowes and the ethereally beautiful Noor Inayat Khan. Their names were immortal. Was it possible that Penny’s wartime work had brought her into contact with those wonderful women? Was it possible that she had been one of their number?

That Penny had spent her missing year as an agent behind enemy lines was Archie’s greatest fantasy. She would have made a fabulous spy, he thought, remembering the many adventures they’d had together over the years. Like the time she took him to Greece when he was fifteen and they jumped off the side of an enormous ferry as it was leaving the dock in Igoumenitsa. It was a slightly extreme way to avoid having to talk to the “boring old boyfriend” Penny claimed to have seen at the other end of the deck, and their luggage was soaked, but it was very exciting and left him exhilarated. Likewise, young Archie had always loved it when halfway through a trip Penny would tell him that to liven things up, they were going to travel under aliases.

“We ’re from Belgium,” was a typical suggestion. “We have never been to London in our lives ...”

They’d once kept up aliases for an entire transatlantic crossing, pretending they were Peggy and Arnie Wilhemsen from Seattle. Penny reeled off their backstory with great aplomb for the “criminally dull” people who shared their table in the ship’s dining room each night. She told them, in a north-west American accent (she was an excellent mimic), that the Wilhemsens had migrated to the US from Norway after the war. They were descended from the great King Cnut ...

They almost came unstuck when Archie, whom Penny had claimed was a medical student, was asked to take a look at someone’s rash. Quick-thinking Penny immediately put her hand to her forehead and told Archie she thought she was about to have “one of her turns.” He gratefully escorted her back to her cabin, suggesting the poor unfortunate with the rash “put some ice on it” as he went. Back in Penny’s cabin, they collapsed into fits of giggles.

“Oh that was killingly funny!” Penny cried. “Put some ice on it! Archie, you are a card.”

“I feel terrible, Auntie Penny. We shouldn’t have lied ...”

Luckily, the chap with the rash found his way to the cruise liner’s sick-bay and didn’t ask Archie’s opinion again.

That whole trip was one Archie would never forget. They’d disembarked in New York and painted the town red, with Penny paying for everything with thick wads of cash. She didn’t trust credit cards. Still didn’t. “It’s never a good idea to leave a trail,” she said.

There was one sticky moment when they found themselves nose-to-nose with a would-be mugger as they walked back to their hotel from a Broadway show but Auntie Penny quickly dispatched the unfortunate chap to the gutter with a move using an umbrella that was straight out of W.E. Fairbairn’s Self-Defence for Women and Girls.

Archie was both thrilled and appalled at the way things unfolded. He would never have believed his great-aunt, who was then in her seventies, could move so fast if he hadn’t seen it with his own eyes. He was sure he couldn’t have reacted so quickly.

“I should have been looking after you, Auntie Penny. But it’s my wrist ...”

“I know, dear,” Penny told him. “I know. And for that I do hold myself accountable.”

You see, once upon a time, Archie had shared Penny’s brand of chutzpah. In the summer of 1990, he was ready for all-comers, imagining his pillow as the school bully when he practised the moves in Major Fairbairn’s Scientific Self-Defence.

One of the hardest Fairbairn manoeuvres to perfect was a backwards roll from lying flat to standing—page forty-three—designed to put our hero back on his feet after being laid out by a blow. Archie remembered how proud he’d been when he finally got it right. When Penny and Josephine visited for a family party, he insisted they come into the living room and watch him execute the perfect flip before they even took their coats off.

That first flip was perfect, though Archie did take out a standard lamp in the process.

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

AARP Members Edition

Your daily source for candid takes on life, comprehensive guides to living well, tips for saving money, inspiring travel, and more – only for AARP membersRecommended for You