AARP Hearing Center

Jose Andres, 55, is a Spanish-born chef famous for his 40-plus restaurants throughout the U.S. and beyond and his hands-on philanthropy. Honored by the James Beard Foundation twice, in 2011 and 2018, as Outstanding Chef and Humanitarian of the Year, Andres is the founder of the nonprofit World Central Kitchen, established after the Haitian earthquake of 2010, when he mobilized volunteers to help feed residents on the devastated island. The organization is still going strong, offering aid to people in crisis around the globe. But that first humanitarian effort in Haiti taught him some valuable lessons — including the importance of listening to the people he’s assisting and being willing to change his strategy (or, more literally, his recipe) in response.

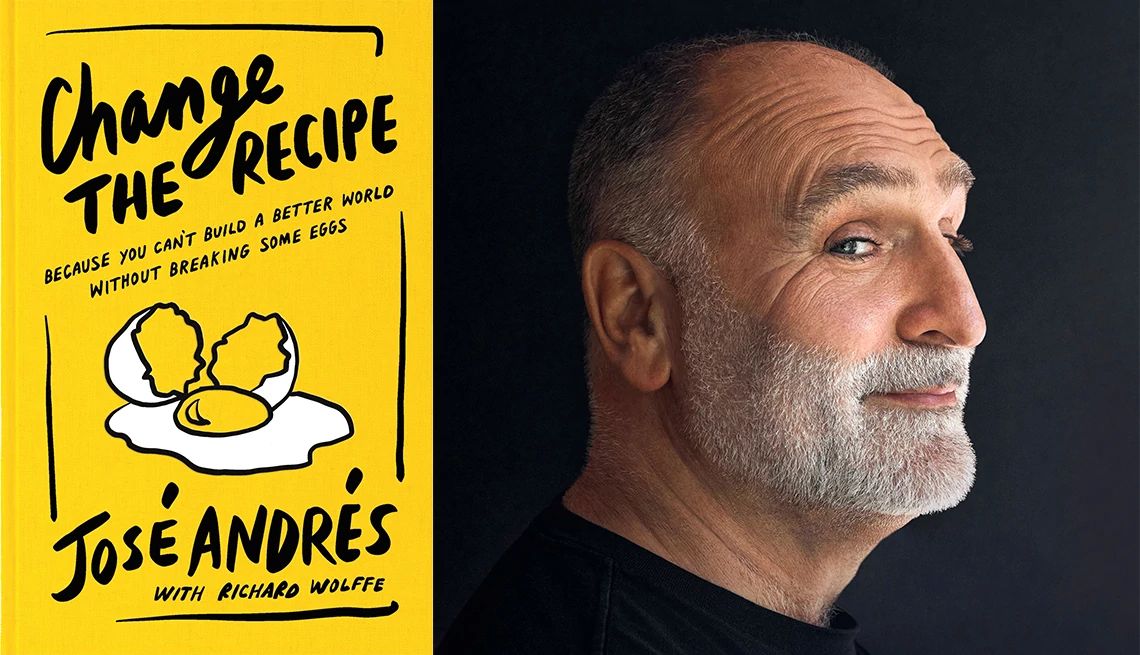

It’s a story José Andrés tells in a chapter called “You Really Don’t Know Everything” from his new book, Change the Recipe: Because You Can’t Build a Better World Without Breaking Some Eggs, written with Richard Wolffe and out April 22, that’s excerpted below. (You can read our interview with the chef here.)

‘You Really Don’t Know Everything’

Watching the images of destruction in Haiti after the huge earthquake in 2010, I had only one idea: let’s go.

It wasn’t like I was thinking I was going to help. It was more that I was going to learn. I had never been to Haiti, and I had never really tried Haitian food, except for a rice dish with mushrooms called djon-djon. It was all new to me. But I knew I could cook, and I had some ideas about how to cook after a disaster. With the help of a Spanish non-governmental organization NGO called CESAL, I traveled to Haiti from the Dominican Republic with two friends: Manolo Vilchez, a bighearted expert on solar cooking, and Carlos Fresneda, his friend and journalist, who spent more time helping than writing. We soon got to work with several solar cookers so we could cook anywhere there was sunshine. It wasn’t very practical: the cooking time was long and the volume we could cook was low. I still love solar as a technology that will improve with time, as we figure out how to feed the world with no carbon emissions.

You Might Also Like

Star Chef Alton Brown Talks Biscuits

In an excerpt from his new book, ‘Food for Thought’ he has the “exquisite pleasure” of replicating his grandmother’s biscuits

Spring Ahead Into Dinner (and Dessert!) With Mark Bittman

The celebrated writer and cookbook author shares three mouthwatering recipes

10 Fantastic Short Story Collections for Your Book Club

No time to read a long novel? A good story can give your group plenty to talk about