Staying Fit

Most weeks, avid readers scanning the best-seller lists are likely to find at least one James Patterson book — either solo projects or collaborations with other writers. They’ll include thrillers, children’s graphic novels, middle-grade fiction and nonfiction. One recent hit is Run, Rose, Run, written with Dolly Parton, who wrote music to go along with it. (Read our interview with the pair about the project.)

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

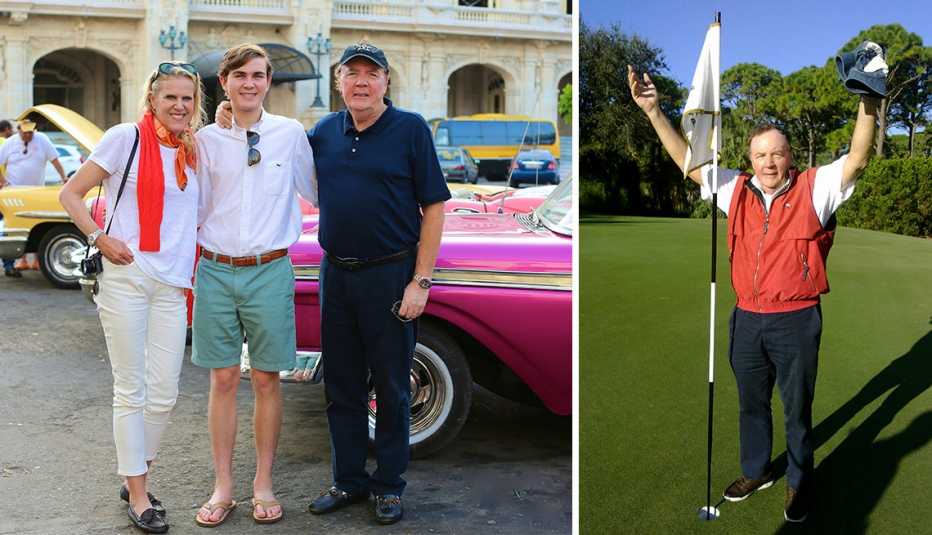

Now, Patterson, 75, has turned his prodigious storytelling skills to looking back on his own journey. His new memoir, James Patterson by James Patterson: The Stories of My Life, is written as a sequence of short, often-amusing tales covering his working-class childhood in Newburgh, New York — where he’d sometimes drink beer at the bar with his dad at age 5 or 6 — and his unlikely path to fame. That included some 25 years in the advertising business (he cowrote the jingle “I’m a Toys ’R’ Us kid”) until he quit, in 1996, to write full-time.

Reading his memoir is a bit like hanging out with a wry, down-to-earth raconteur who, by many accounts, just happens to sell more books than anyone else on the planet.

Enjoy a glimpse into Patterson as he tells it like it was.

You’re slipping, James

According to Patterson family lore, on March 22, 1947, I nearly died at birth at St. Luke’s Hospital in Newburgh, New York. I don’t remember, but I did live to tell about it.

Let’s start with my father. Charles Henry Patterson was a quiet but tough man who came from tough times and from a tough river town.

My dad grew up in the Newburgh poorhouse (think about that for a second or two). It was called the Pogie. His mom was the charwoman there. She cleaned the kitchens and bathrooms, worked, she said, from “7 to 7, seven days a week.” For her long, hard work, she and my father got to share a single room on the basement floor. They weren’t homeless, but they were damn close. My father never met his father, at least not as far as he could remember.

My mother, Isabelle Ann, attended high school with my dad. After college she became a fourth grade teacher at St. Patrick’s, one of the four Catholic schools in Newburgh. She made next to nothing. Maybe even a little less than that. I’m surprised the parish priests didn’t ask her to pay them for the privilege of teaching at their school. Several nights a week, she would be bent over the dining-room table grading papers until 9 or 10.

She had a cool mission as a teacher: She wanted to turn mirrors into windows. She pretty much followed the same philosophy at home. Mirrors, physical or symbolic, weren’t big in the Patterson house.

My sisters — Mary Ellen, Carole and Teresa — ruled the roost. In their view of the world, I was hired help. I was muscle. I was their minion. So I handled the garbage detail, the lawn work, the snow removal, and the repair of bicycles, small electrical appliances, deflated balls of all sizes and shapes. We were a very ball-sy family.

I was always a good student, driven to be number one in, well, everything, but I’d get a 97 on a test and my mom or dad would say, “How come you didn’t get a hundred? You’re slipping, James.”

The idea I had growing up — and I held on to it into my 40s — was that my folks only cared about me as long as I was number one in my class. I don’t blame them, because I feel they were doing the best that they could. I think they honestly believed the next Great Depression was just around the corner, and they always clung to, Careful. Careful. Go slow. Look both ways. Then look again. Your best isn’t good enough. You’re slipping, James.

My favorite dad story

Just a few weeks before my father got shipped out to fight in World War II, he received a long-distance phone call [from a man who] identified himself as George Hazelton from Port Jervis, a town about 40 miles from Newburgh. George told my dad he was about to leave for the Pacific theater with the Navy, and the night before, his father had said to him, “George, you know we love you very much, and you’re about to go off to fight in this horrible war, so we have to tell you something that we’ve kept from you all these years. We’re not your natural parents. We adopted you when you were 1 year old.”

Then George Hazelton told my father — over the phone — that he was his brother.

So Charles Patterson and George Hazelton, two brothers who still hadn’t actually met, both went off to fight for their country in World War II.

Miraculously, they both also came home. They became best friends, extremely loyal and loving toward one another. The thing I remember best about the two of them was that when they were together, they would laugh and laugh. And my father didn’t laugh all that much.

My father would sometimes tear up when he told the story about how he and his big brother, George, found one another. I think it was the only time I ever saw him cry.

A few years after the war ended, my Uncle George called my father again. This time he started with the punch line: “I found our father.”