Staying Fit

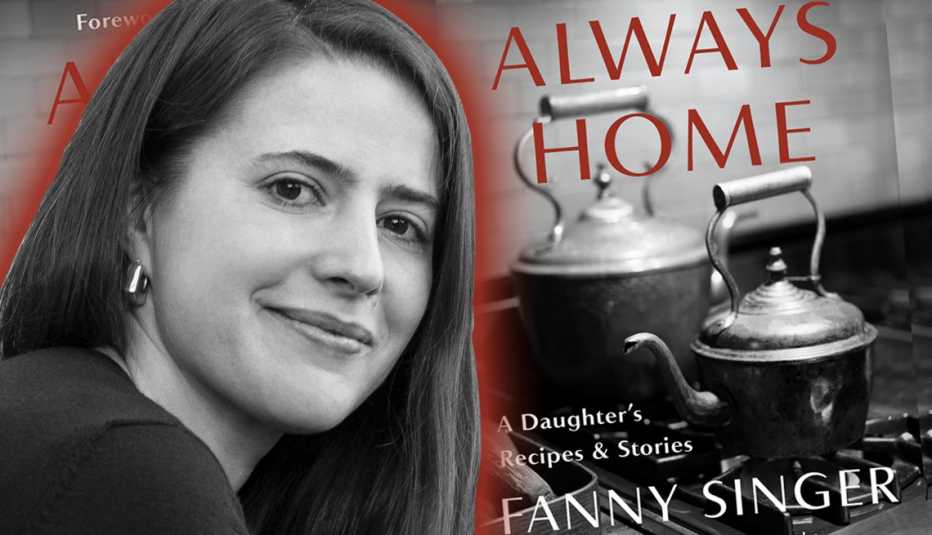

Master chef Alice Waters pioneered California cuisine at her famed Berkeley restaurant, Chez Panisse, emphasizing organic local bounty such as farm-to-table vegetables and fruits and sustainably produced meats and seafood. Now her daughter, 36-year-old Fanny Singer, offers Always Home: A Daughter’s Recipes and Stories, a memoir about coming of age with a famous, food-focused mom. It includes a foreword by Waters, 75, some delicious recipes, lush descriptions of travel and feasts, and evocative black-and-white photographs by Brigitte Lacombe.

In the first chapter, Singer discusses her mother’s reverence for beauty — whether in the form of food or objects or her surroundings — as a reflection of Waters’ lifelong passion for shaping her world into something lovely for herself and others. Read or listen to the start of Singer’s story below.

Beauty as a Language of Care

My mom speaks a language of beauty that I think very few are fluent in. In fact, only my mom can use the word beauty without its sounding cliché to me (although I am a jaded member of the art community, where the word beauty is frowned upon). When musing on my mom’s particular contributions to civic life in Berkeley, a philanthropist and longtime supporter of her Edible Schoolyard Project suggested to me that above all she ought to be credited for emphasizing the importance of beauty in one’s life. I think it’s true that beauty is generally now considered to be superfluous, something merely cosmetic, but the way my mom thinks about it — which is to say practices it, really — places it at the core of a set of values she’s evolved into a kind of pedagogy. The first Edible Schoolyard (at the Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Berkeley), which I sometimes think of as my mother’s second child, was in a sense conceived out of beauty, or a perceived absence thereof. When the school’s principal caught out my mom for publicly maligning its quasi-derelict appearance (she had said something offhand to a reporter for a local paper), conversations began that resulted in the ripping up of an acre of asphalt.

Within a year, the Edible Schoolyard Project had begun to take shape. That once-litter-strewn stretch of pitch had been replaced with a nutrient-generating cover crop of alfalfa, fava, and clover. Soon thereafter, a truly magical garden (a friend’s five-year-old son recently told him that it was his “favorite place in the whole world”) began to take shape, and its tending by students was woven into the curriculum (soil sampling in biology, threshing ancient grains in history, and so forth). At the far end of the garden is a Kitchen Classroom, a structure containing a culinary facility in which students are, on a weekly basis, instructed in the basics of making and sharing delicious food, under the tutelage of one of the most empathic and gifted teachers around, the aptly named Esther Cook.

In the early days, because of overflow, there was a temporary classroom — in one of those deeply dispiriting trailer things usually reserved for use by construction site managers — that was placed on the school grounds in close proximity to the Kitchen Classroom building. My mom, her tolerance for the industrial taupe of the prefab kitchen building having worn thin, dipped, I believe, into her personal accounts to have the structure repainted aubergine. The crew charged with this task mistook the nearby classroom trailer for a related building and, in error, repainted it too. The next week, my mom received a handwritten card from the sixth graders whose class she had inadvertently beautified, thanking her for making their space feel special — thanking her for caring about them. I was always struck by the poignancy of that story, because it demonstrates that those things I often perceive as my mom’s utter folly (example: she also repaints our recycling and garbage bin brown every few years because she finds the underlying powder blue offensive) translate to a language of care. It’s not really about beauty in the end, but about care. If food is plated carefully, it will almost always be beautiful. If a child is surrounded by lush color, by growing places, by the variegated plumage of the chickens that run wild across her schoolyard, that child, I would wager, feels and registers that care on a profound, if subconscious, level.

It would be a bit tautological to suggest that beauty and care were things I grew up with and felt — beauty was the total fabric of my existence. I always think it’s important, however, to stress that my mom’s fixation on beauty never approached preciousness. The reason this whole system functioned was the general lack of sentiment attached to any given object. Yes, an antique bowl from France might be loved, but it would also be used and brazenly put in the dishwasher and crazed and glued and finally broken beyond repair, but that was the only way to live with things — why buy them otherwise? One would think this almost cavalier attitude could not live alongside the impulse to acquire nice objects — our house is full to bursting with culinary treasures, flea market finds, linens, books — but for my mom, atmosphere (which is about so much more than appearance) extends well beyond the organization of belongings. I am wary of overemphasizing the degree to which she is intolerant of poorly conceived spaces — especially ones in which a reception or meal or some other variety of convivial activity is meant to take place — as it can make her seem disproportionately blinkered, even insensitive to the widely held belief that hers is an unachievably romantic existence. Yes, she will arrive at the governor of California’s mansion in Sacramento for the inaugural event she’s catering and immediately insist on starting a fire in the disused, presumed- decorative fireplace — for grilling the bread for bruschetta, of course! Despite the initial eye-rolling, sweating, and concerned protestations from the staff, my mother prevails — and the first guests arrive to the smell of woodsmoke and grilling bread, an elemental perfume. The grilled bread, the handmade mozzarella, still warm from the brine, the splash of green olive oil, together with the aroma of the room, make the place feel like no other well-heeled political event out there.

All of this amounts to an attitude toward living born of sensitivity to one’s surroundings, dedicated to care, to the slow, meaningful collection of objects — not to money or privilege. She built her sensibility over decades of travel, of work, of friendship. The long-ago generosity of a stranger in Turkey when she was twenty — a young goatherd who left a bowl of fresh milk outside her tent — has everything to do with how she extends herself, or elaborates her sense of atmosphere, into a public milieu meant to be experienced and enjoyed beyond herself. To become a restaurateur (or “restauratrice,” as my mother has always put it, proud to be a woman occupying a traditionally male role), you have to want to share something of yourself with others; it might be among the most generous, most intimate professions out there. And Chez Panisse was built by a group of friends in what was originally a house, so, I think, a feeling of intimacy — of visiting someone’s home — is especially redolent still.

My mom basically never stops creating atmosphere, whether her focus is a room of her own, a room in the restaurant, or a room in the home of an unsuspecting Airbnb host. No one, and I mean no one, gets to work as swiftly as my mom when there’s a space — which is to say, most spaces — in “need” of a few alterations. If she has recently landed in a rental property in which she plans to remain for even the briefest of stays, she assumes the mien of a five-star general on a mission. She shifts heavy things she would normally ask me to move, she delegates if there’s anyone to delegate to, she finds a room — preferably a capacious closet — into which undesirables can be ruthlessly deposited. Vase shaped like a flying pig? Decorative indoor weather-vane sculpture? Cutting boards shaped like the things meant to be cut upon them? Into the closet. A scribbled map is drawn to remind herself, and any other witnesses, where these items must be returned prior to departure. Inevitably, the pig vase meets its (un)timely demise in the back-and-forth. We are almost never returned a security deposit.

But sometimes it’s not a question of the pig vase; it’s just a matter of lighting, of a bulb that needs to be replaced with something of a lower wattage or perhaps just a lamp that needs a little dimming or a leaf of paper wrapped around it to dull the glare. Yet other times, just the slightest of interventions is required: a burning branch of rosemary, waved through room after room like a smudge stick to chase out the demons. If I ever smell the scent of burning rosemary anywhere outside of Berkeley, I feel myself lose equilibrium for a moment — it’s as if my mom has just trailed through the room, expunging the ghosts through the introduction of her own.

Excerpted from Always Home by Fanny Singer. Copyright © 2020 by Alfred A. Knopf. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Available at Amazon.com, Bookshop.org (where your purchase supports independent bookstores), Barnes & Noble (bn.com) and wherever else books are sold.

More From AARP

Excerpt From Anne Tyler's 'Redhead by the Side of the Road'

Meet the character who drives the popular author's new novelExclusive First Look at New Novel by Author of 'A Man Called Ove'

Meet the colorful characters in Swedish writer Fredrik Backman's upcoming gem, 'Anxious People'Excerpted First Chapter of Hilary Mantel's 'The Mirror and the Light'

Thomas Cromwell's fall is coming as Henry VIII takes a third wife