Staying Fit

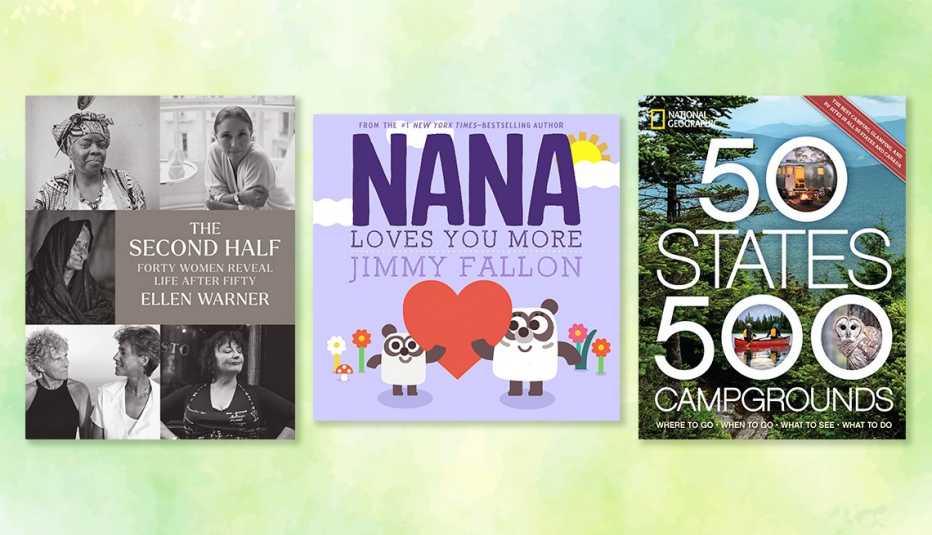

This year has started off with a bang for book lovers: The first three months of 2022 have brought loads of must-read novels and fascinating nonfiction of all stripes. These are 22 standouts, including releases big (the best seller from Dolly Parton and James Patterson, for one) and small (Jimmy Fallon’s sweet children’s book, Nana Loves You More).

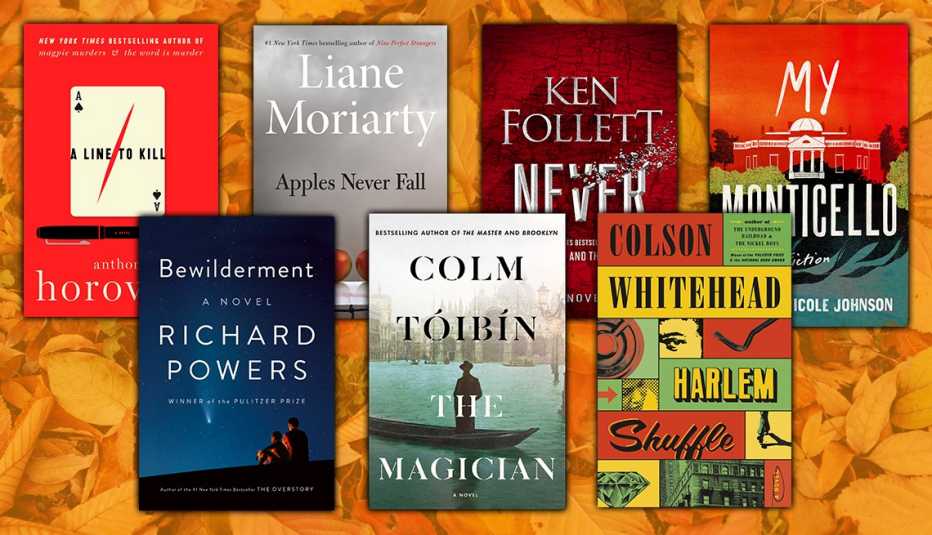

Fiction

The Recovery Agent by Janet Evanovich

Evanovich’s many fans can now dive into a new spin-off series featuring Gabriela Rose, the sexy weapons expert (now a recovery agent, hired to find and return lost or stolen valuables and missing people) from the author’s hugely popular Stephanie Plum novels. It’s a breezy, action-packed caper, told with JE’s signature humor. Gabriela needs money for her family, and somehow (it’s complicated, but the ghost of the pirate Blackbeard’s lover is involved) ends up in the jungles of Peru searching for hidden treasure — with, alas, her handsome-but-annoying ex-husband, Rafer. Together they have to outsmart a ruthless drug lord, and try to get the treasure without getting murdered, or murdering each other. (March 22)

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

This wonderful novel from Fowler, the author of the PEN/Faulkner-award-winning We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, is a fictionalization of the lives of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth and his family, with many details imagined but the most seminal events based on deeply researched historical facts. John was one of 10 siblings (only six reached adulthood) fathered by the erratic, alcoholic and egotistical Junius Booth, the most famous Shakespearean actor of his day. While Junius is off touring and carousing, his family spends many years barely getting by in a cabin near Baltimore (Tudor Hall, a historic site in Bel Air, Maryland, that you can visit today), and is gradually swept up by growing political tensions that lead to the Civil War. (March 8)

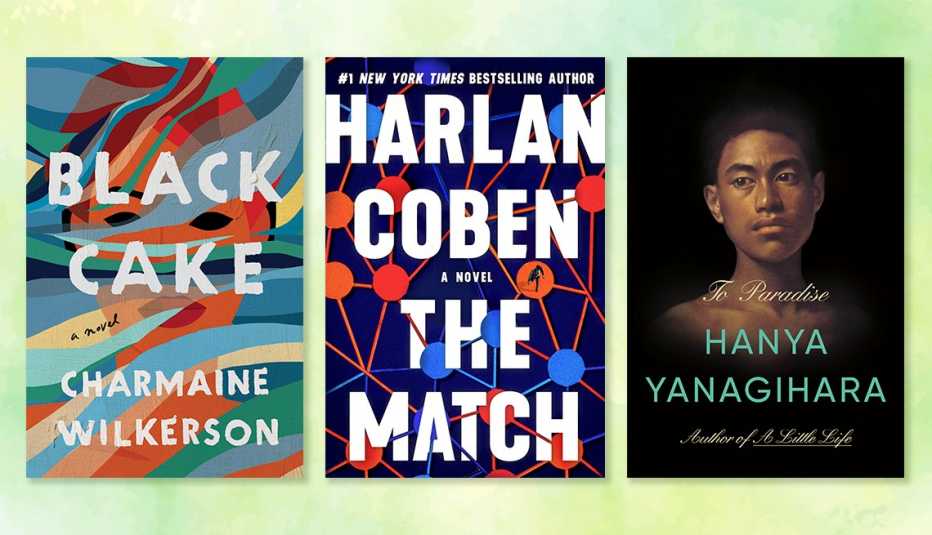

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

Hulu is already working on a TV series based on this absorbing book, about a family’s complicated history that begins to emerge after the death of its Caribbean-born matriarch, Eleanor Bennett. When Eleanor’s two adult children, Byron and Benny, travel to California upon her passing, Eleanor’s lawyer hands them an audio recording in which their mother spins a remarkable story about a young swimmer named Covey and a tragic incident that changed the course of her life and the lives of others. She also tells her children that she has baked a traditional Caribbean black cake and left it for them in her freezer, adding, “I want you to sit down together and share the cake when the time is right. You’ll know when.” And, eventually, after receiving the shock of their lives, they do. (Feb. 1)

Run, Rose, Run by James Patterson and Dolly Parton

A collaboration between one of the country’s most beloved musicians and the blockbuster author, this fast-paced novel has been a No. 1 best seller since its release a few weeks ago. Patterson, 74, is the mastermind behind the novel’s cliff-hanger chapter endings, but you can hear Parton, 76, loud and clear in the two main characters: AnnieLee Keyes, a gifted, feisty young singer who hitchhikes her way to Nashville carrying little more than “big dreams and faded jeans” (the title of one of her songs, included on the accompanying soundtrack by Parton), and Ruthanna Ryder, a seasoned country-music megastar — to be played by Parton in the movie version — who takes AnnieLee under her wing. It’s suspenseful and fun, with a dose of romance. For more, read our interview with the two authors. (March 7)

The Match by Harlan Coben

This is Coben’s second thriller featuring Wilde, the character who was rescued from a feral childhood in the wilderness, first introduced in his best-selling The Boy From the Woods. Wilde has given up trying to live a normal, domestic life, focused instead on finding the identity of his parents and how he ended up abandoned. A DNA match sets him on a promising path that turns dangerous when clues lead him toward a killer. It’s a classic Coben-style (twisty) story, quite probably already on its way to become a TV series adaption like many of his other novels — The Woods, The Stranger and Safe among them. (March 15)

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

Another weighty and, yes, dark novel from the author of 2015’s A Little Life, her latest is an arguably even more complex (in terms of plot and structure) exploration of tragic love, suffering and hope. It consists of three stories set in different time periods and altered realities, with overlapping characters. Many are gay men, whom we encounter in varying contexts — including the 1890s, in a New York City where homosexuality is legal and accepted, and in Hawaii and New York during the AIDS crisis of the 1990s. The last section is the most searing, a vivid portrayal of a pandemic-plagued, climate-changed, dystopian New York set some 70 years in the future that feels all too real. If it sounds bleak, it is, but it’s also brilliant. (Jan. 11)

French Braid by Anne Tyler

This new novel is classic Anne Tyler, with warmth, wisdom and a Baltimore family at its center. The story begins in 2010, with two cousins’ awkward encounter in Philadelphia’s 30th Street train station, before jumping back to 1959 and their grandparents: Robin and Mercy Garrett, who are on their first and only family vacation with their two teenage daughters and young son. As the decades pass, there are marriages and births, but what remains consistent through the generations is a lack of candor (the couple never tell their kids that Mercy has moved out of the family home to pursue her dream of becoming an artist) and a tension between yearning for and resisting familial intimacy. (March 22)

The Lightning Rod by Brad Meltzer

The second thriller in Meltzer’s new series, following The Escape Artist, brings back mortician Jim “Zig” Zigarowski and artist Nola Brown (whose life Zig saved in the first book). After he discovers a telling clue while working on the body of a murdered military officer, Zig ends up following a trail that leads to both Nola and some dangerous Cold War secrets. Meltzer loves taking readers into secret underground bunkers, and here he does so again, as the characters shine an unwanted light into the dark corners of the U.S. government’s Strategic National Stockpile — government facilities for large-scale attacks and biological threats. AARP members can read an excerpt here. (March 8)